Arnie Alpert is an activist and journalist with an interest in labor history and social justice movements. He was one of the leaders of the effort to install the Elizabeth Gurley Flynn historic marker. He writes the “Active with the Activists” column for InDepthNH.org here: https://indepthnh.org/series/active-with-the-activists/

By ARNIE ALPERT

You’ve probably seen them alongside New Hampshire’s roadways, green metal plaques with white lettering describing some person, place, or event with significance to the state’s history. We’ve got one at the State House, one at the Mount Washington Hotel, and one at the site of Noyes Academy in Canaan. There’s one at the 45th parallel in Clarksville, one for Norris Cotton in Warren, and one for the Molly Stark Cannon in New Boston. All told there are now 279 of them.

The State calls them “historical highway markers” and says they “illustrate the depth and complexity of our history and the people who made it, from the last Revolutionary War soldier to contemporary sports figures to poets and painters who used New Hampshire for inspiration; from 18th-century meeting houses to stone arch bridges to long-lost villages; from factories and cemeteries to sites where international history was made.”

Any municipality, agency, organization or individual with an idea for a historical highway marker can submit a proposal to the Division of Historical Resources with a petition signed by at least 20 New Hampshire residents, a draft text for the marker, and background materials which thoroughly document the subject and its history.

Under the Division’s latest guidelines, nominations should highlight someone, somewhere, or something that “had a significant impact and has demonstrated historical significance. The significance of the subject, particularly for continuing events and organizations, must be historically established rather than of contemporary interest alone.” In addition, the subject of the marker must have a clear connection to New Hampshire. Markers whose historical significance “extends beyond the locality, preferably demonstrating statewide or national significance” are among the program’s priorities.

The birthplace of Elizabeth Gurley Flynn in Concord in 1890 is a perfect subject for such a marker.

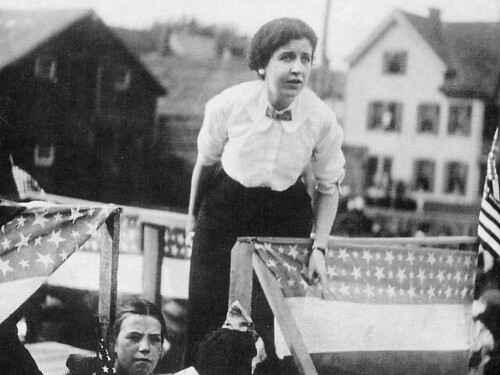

Flynn first gained notoriety as a soapbox speaker at age sixteen, when she was arrested after speaking at a socialist rally in Manhattan’s theatre district. The New York Times reported the incident, calling Flynn “a mere slip of a girl, with snapping black eyes and expressive features.” Disorderly conduct charges were soon dropped, but her career – and habit of getting arrested for activities which should have been protected under the First Amendment – was launched.

By age 17, Flynn was supporting strikers as a member of the radical union, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which believed in organizing across industrial rather than craft lines, and which believed in organizing all workers regardless of race, sex, or national origin. Flynn was soon crisscrossing the country, supporting the IWW’s free speech fights in the northwest and organizing drives from Minnesota to New Jersey, including the 1912 “Bread and Roses” textile strike in Lawrence.

Motivated initially by the working class poverty she witnessed in New England mill towns, Flynn believed that socialism was the answer to the ills of capitalism and in particular to the oppression of women. When the IWW was largely crushed during World War I and the subsequent “Red Scare,” Flynn organized the Workers Defense Union to raise funds and political support for labor activists facing prison and death for their activities. It was at that time that she joined the founders of the American Civil Liberties Union as a charter member and served on their board.

At age 46, when her reputation for oratory and advocacy had been well established for decades, she joined the Communist Party and soon became a member of its National Committee. Fifteen years later, with the Cold War and the second Red Scare heating up, she was arrested for perhaps the twelfth time under a federal law known as the Smith Act. In essence, the Smith Act made it illegal to be a Communist, under the assumption that the Communist Party was committed to the violent overthrow of the government. Flynn’s self-defense at trial – considered by AmericanRhetoric.com to be one of the 100 top speeches in American history – emphasized her own political beliefs and insisted, “Never have I, and not now do I, intend to advocate the overthrow of government by force and violence, nor do I intend to bring about such overthrow.”

Although she was convicted and sent to federal prison for 28 months, the Smith Act itself was largely decapitated by later Supreme Court decisions (Yates and Noto cases) which found a distinction between theoretical advocacy of revolution and actual incitement to violence, and reinforced the importance of the First Amendment’s protection of free speech.

Flynn’s story started in Concord, where she was the first child of Annie Gurley, a seamstress, and Thomas Flynn, a quarry worker. It was in their household that the young Elizabeth developed a passion for reading, including Thomas Paine and the U.S. Constitution alongside Karl Marx and Mary Wollstonecraft. Her mother supported women’s suffrage and insisted on using female doctors. Her dad proudly espoused the cause of Irish nationalism and gravitated toward socialism as the family moved from Concord to Manchester, then Cleveland, N. Adams, Massachusetts, and the Bronx. That’s where Elizabeth grew up, went to school, joined the debating club, and took to the soapboxes as a street speaker.

That the Elizabeth Gurley Flynn historic marker, now standing at the corner of Court and Montgomery Streets, would be controversial is hardly surprising. Flynn lived her life awash in controversy, after all.

That life has long been a subject of historical study; she is the subject of three scholarly biographies and features in untold numbers of books about the history of America’s labor and feminist movements. She shows up in songs, including IWW songwriter and martyr Joe Hill’s “The Rebel Girl,” which he said just before his execution was inspired by Flynn. She even shows up as a character in Jess Walter’s 2020 historical novel, The Cold Millions, set during the IWW free speech fight in Spokane. Her place in history is secure. Now, with a green and white marker near her Montgomery Street birthplace, it will become better known that her controversial and history-making life began in New Hampshire.