Whatever the workplace, “the fundamentals are the same”

By Arnie Alpert, Active with the Activists

Arnie Alpert spent decades as a community organizer/educator in NH movements for social justice and peace. Officially retired since 2020, he keeps his hands (and feet) in the activist world while writing about past and present social movements.

HANOVER—Although the Dartmouth College administration has publicly refused to negotiate with its highest profile union, labor movement activity, including a possible strike by graduate students, continues to intensify on the Hanover campus.

After months of bargaining, GOLD-UE, the union representing graduate student employees, has reached tentative agreements with the administration in several areas, including grievance procedures, discipline and discharge, and non-discrimination. But other provisions remain contested and last week GOLD-UE members voted to authorize a strike if their demands are not met.

The administration says, “Dartmouth is working hard to bargain a fair contract,” and has offered a 17.5% pay raise with guaranteed annual increases to keep up with inflation. However, the union and the administration are not yet on the same page. After the latest negotiation session, April 18, the union informed its members, “Despite encouraging progress on compensation, medical funds, and immigration fee coverage, Dartmouth continues to entirely reject many core benefits: dental, vision, retirement, childcare, and more.”

“Dartmouth has one more opportunity at the April 25th bargaining session to address the outstanding core issues,” the union statement said. “Following this session, we will hold a general body meeting on April 29th to collectively determine if their offer is sufficient or if we should escalate in response.”

“Dartmouth is continuing to bargain in good faith,” states a 6-page document, “FAQs About Graduate Student Unionization,” posted by the college’s provost. “Given the progress made at the bargaining table so far, the generous proposals Dartmouth has made, and the fact that Dartmouth graduate students already receive a comprehensive package of stipend, health benefits, and tuition remission, we believe we should be able to reach a fair contract agreement via the bargaining process. As such, a strike is entirely unwarranted,” the statement said.

The administration statement says faculty members should not interfere with strike activities, initiate discussions about a strike, or ask their teaching assistants if they plan to walk out. It states that faculty are part of management and says, “A graduate-student strike does not change a faculty member’s obligation to perform their duties, including submitting grades or conducting class.”

“Faculty can hire temporary workers to cover the staffing gap created by a strike,” it adds.

Ian Scott and Hosaena Tilahun are members of the Student Worker Collective at Dartmouth ARNIE ALPERT photo

Negotiations are also underway between Dartmouth and Local 560 of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which has two longstanding contracts covering hundreds of campus workers such as security personnel, custodians, groundskeepers, and cooks. Contract talks are going on, as well, with Dartmouth librarians, who last year voted to join the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees.

But Dartmouth has stubbornly refused to negotiate with its basketball team, which voted in March to join Local 560. The New England office of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) has ruled the players qualify as employees and are eligible to engage in collective bargaining. But in a statement issued in March the administration said it would refuse to bargain. “This will likely result in SEIU Local 560 filing an unfair labor practice charge with the NLRB, which we would appeal,” they said in an emailed statement.

Dartmouth’s president, Sian Beilock, followed up with a Wall Street Journal op-ed on April 12 in which she said the college will fight the basketball union “all the way to the Supreme Court if that’s what it takes to prevent this misguided development from taking hold.”

“Our resistance to the decision isn’t because we oppose labor unions,” she wrote. “Dartmouth has more than 1,500 union employees across ?ve unions—including campus services employees, library workers, and teaching and research assistants—all of whom we are proud to work with through collective bargaining.”

“It’s time for President Beilock to stop repeating that her administration ‘doesn’t oppose unions,’” responded Chris Peck, a Dartmouth painter who heads Local 560. “Dartmouth is currently in violation of federal labor law by refusing to bargain with a certified bargaining unit. That is a policy shift and is a clear sign to all of the unions on campus of what this administration is capable of.”

“Even more troubling,” Peck said, “this administration has also allowed a small group of disgruntled donors to directly threaten the players by denying them access to jobs and internships. While we recognize that the vast majority of alumni do not countenance such tactics, such a campaign is entirely incompatible with Dartmouth’s community standards and President Beilock’s professed commitment to dialogue and ‘safe spaces.’”

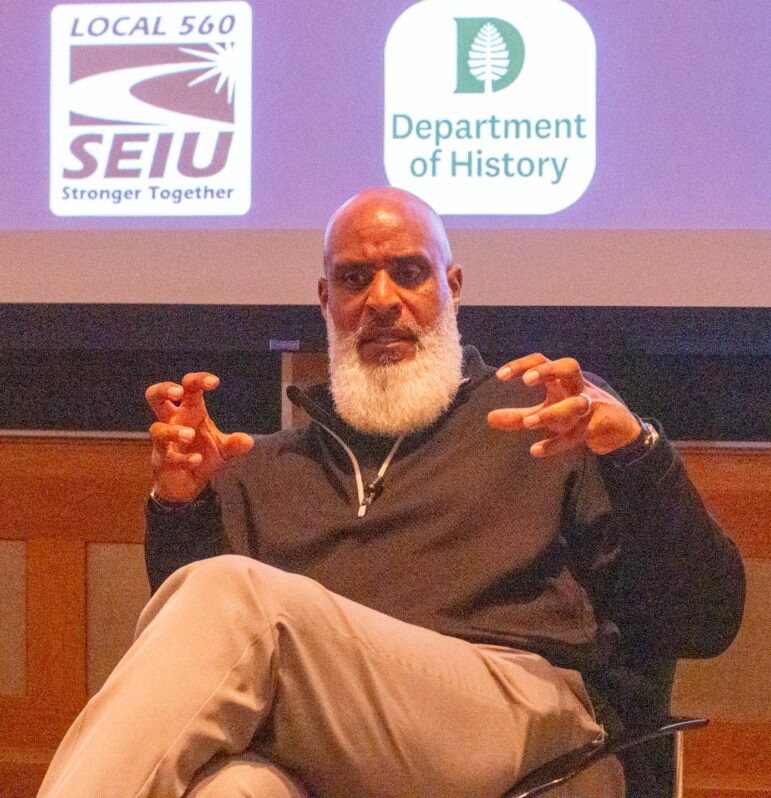

Tony Clark, Executive Director of the Major League Baseball Players Association. ARNIE ALPERT photo

For Jackson Monroe, a player and member of the Dartmouth class of 2026, the issue is not about wages or whether the players should be considered “professionals” as President Beilock charges. It’s about student rights and access to health care. “If I were to hurt myself playing basketball for the school, and I have to go get an MRI or something, that comes out of my own pocket, the school doesn’t cover that,” he said.

He also wants to challenge Ivy League rules that restrict the amount of time players can practice. “We love our game, we love our sport, we want to practice it a ton,” he said. “We’re not doing this because we want to practice less.”

The question of whether basketball players should be considered workers with the right to unionize has attracted national attention and has also attracted at least one high-profile visitor to the Hanover campus. Tony Clark, a former big league baseball player who now serves as executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, was on campus April 14 and 15 to meet Dartmouth athletes and speak at a forum sponsored by the SEIU and several academic departments. For him, unions at their essence are about giving people a voice in the workplace, whether it’s a mine, an office, or a baseball field. And whenever people step forward to shake things up, according to Clark, defenders of the status quo respond like Chicken Little that the sky is falling.

For the baseball players union, he said, “at each moment we sat down to negotiate a new collective bargaining, or each moment where there was a strike, where there was a lockout, the sky was always falling. It was always falling, and it was going to collapse, and the foundation was going to break in the end, and the sun and the moon, and all of those things were going to happen because of what the union was asking for.”

But each time, they worked it out and union members returned to playing ball.

“At its core,” he said, unions are about “protecting and advancing the rights and interests of our members. You may not like it. You may not agree with it. But I’ll never apologize for us fighting for the things that we believe are right in protection of our workplace environment, rules and regulations that determine and dictate the course of our work on any given day.”

In 2022, the baseball players union joined the AFL-CIO, the nation’s largest labor federation. Regardless of the workplace, Clark said, “the fundamentals are the same.”

Bethany Moreton, a Dartmouth history professor who hosted the forum with Clark, sees the progress of unionization at Dartmouth and in other workplaces as a democracy movement. “To watch people insist that they get to have some say over their workplace is heartening to see,” she said, “especially from the students but from others as well.” For Moreton, the new campus union drives are tied to critiques of the gig economy and conflicting views of who is a worker. Over decades of workplace struggles, she said, the labor movement has “managed to make the category of employee a container of certain kinds of enforceable rights.” By identifying themselves as workers, the basketball players and the grad students are saying they are entitled to those rights, too.

Dartmouth faculty are not unionized, but they do have a chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) which has issued statements in support of the undergrad and graduate student employee unions. A separate statement, signed by 250 faculty members last October 29, tied the college’s problems attracting new staff to “the Upper Valley’s exploding housing, childcare, and eldercare costs,” very much like issues raised by GOLD-UE.

Pamela Voekel, also a history professor, said she was surprised how easy it was to gather the 250 signatures. “The faculty is very supportive of what the graduate students are doing,” she said.

At the forum where Tony Clark spoke, Hosaena Tilahun, a Dartmouth junior, announced the latest union drive on campus. A majority of the school’s 110 undergraduate assistants (resident advisors) have submitted a petition to the NLRB to join the Student Worker Collective at Dartmouth, a union which has already won impressive wage gains for student dining hall workers. The NLRB has not yet scheduled an election.