InDepthNH.org series on Medical Errors in NH Hospitals

Part 1: Serious Medical Errors Plague NH Hospitals

Part 2: Disagreement On How To Stop Serious, Preventable Medical Errors in NH Hospitals

Part 3a: Doctor’s in the House: Tips on Staying Safe in the Hospital

Part 3b: How To Become Your Own Patient Safety Advocate in NH

Part 3c: Telling Noah’s Story to Stop Medical Errors in NH Hospitals

By Nancy West

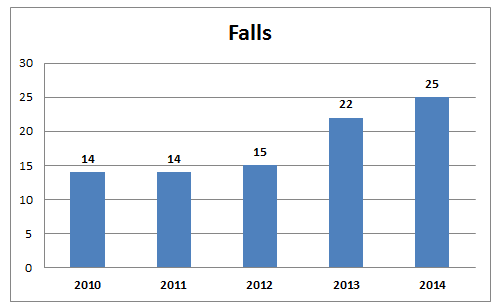

In 2010, New Hampshire’s hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers reported 42 adverse events and 73 in 2014. They are also called “never events” because they are never supposed to happen.

The 29 reportable events include serious or fatal preventable errors such as surgery on the wrong person or body part, objects left inside a patient after surgery, falls, burns, pressure sores, assaults and sexual assaults.

Dr. Roger Resar, an assistant professor at the Mayo Clinic who also works with the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI), has pioneered ways to reduce or eliminate such errors.

“When it comes to (hospital) patient safety, we are not much better off than we were 10 or 15 years ago,” Resar said.

He was critical of the kinds of typical root cause analysis used in New Hampshire and many other states. By law in New Hampshire, the 29 adverse events must be reported along with a reduction plan to the state Bureau of Licensing and Certification.

Dr. Roger Resar

“Root cause analyses are a waste of time,” said Resar.

Resar, who still works occasionally as a consultant to hospitals, is a proponent of IHI’s Global Trigger Tool.

The trigger tool is described as “an easy-to-use method for accurately identifying adverse events (harm) and measuring the rate of adverse events over time.”

Michael Fleming, the director of the state Bureau of Licensing and Certification and oversees the adverse events reporting, disagreed with Resar on the quality of hospital care today.

“If somebody said to me that hospitals are not safer than they were 10 years ago, that’s not the case,” Fleming said.  Source: Department of Health and Human Services[/caption]

Source: Department of Health and Human Services[/caption]

Common problems that lead to falls including sedating elderly patients who are fall risks and failure to have a workable toileting plan.

“There are certain patients who are at a higher risk for falls if they have sedatives. We need to understand who they are and change our prescribing practices,” Resar said.

The fix doesn’t have to be expensive, he said. But the research needs to dig deeper to find out the real reason events happen. Too often root cause analyses find a scapegoat, initiate an unsustainable new protocol, promise to improve staff education and then move on, he said.

“You’ve got to be imaginative in your solutions. If a nurse (or doctor) has to do more, then that is not necessarily a solution,” Resar said. “Hard work and vigilance are very admirable qualities, but they will never be able to create a reliable process.”

Hospitals often promise more education and protocol review, he said. “All of these are educational concepts. I just don’t see where the plan moving forward, how that will ever give them a reliable process.”

How it started

Jill Rosenthal, senior program director at National Academy of State Health Policy, said the adverse events reporting laws in 26 states and the District of Columbia, came about as a response to an Institute of Medicine study 16 years ago.

The well-known study sounded the alarm about preventable deaths from medical errors in hospitals. The 1999 publication “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System” estimated that as many as 98,000 people die every year from preventable medical errors in hospitals.

Today, experts say there are closer to four times that many deaths due to preventable medical errors in hospitals. IOM recommended that states create mandatory reporting systems on adverse events, but the movement seems to have stalled, Rosenthal said.

Each state created a different system of what to report and whether the reports should be made public. The original plan was to have each state report the same information to a national system to find solutions to similar problems.

“There was never funding available. Each state went out and did the best they could with the resources they had,” Rosenthal said.

Big 3 in New Hampshire

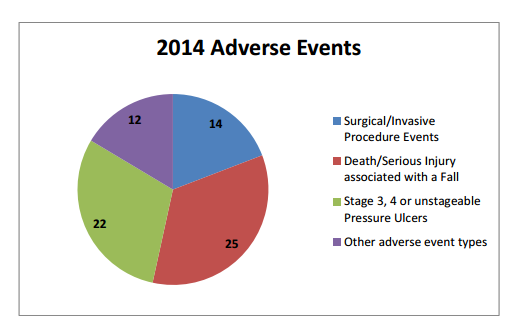

Falls, pressure sores, and surgical errors made up 83 percent of all adverse events in 2014. The report details some of the general problems and suggested solutions. Detailed plans for each event at each hospital are confidential and the events must be serious or fatal so they don’t include all errors.

The Adverse Events Report plan moving forward on falls included:

Link specific interventions to prevent a fall to the fall risk assessment score, staff education refresher on fall prevention, and expand the act of purposeful rounding to include toileting at least hourly.

“Current standard is to ‘ask’ the patient but in high risk cases we may need to trial a new standard of actually taking patients to the bathroom,” the report stated.

On surgical errors, the report said they were caused in general by: Frequent hand-offs of information during the continuum of care; vital information is sometimes misrepresented or lost completely as it is handed off along the way; over-reliance on a standardized checklist …

“Evidence-based practices demonstrate a reduction or elimination of these errors with stronger leadership by surgeons in the final team time out process which occurs just prior to incision, by having the surgeon ask each team member to introduce themselves and their role, review unique patient concerns, and end with a request to everyone involved to speak up if they have any concerns at any point during the procedure.”

It goes on to say “Introduction of the patient to the team serves to enhance greater personal engagement and investment in good outcomes by each team member.”

Moving forward

Diefendorf said New Hampshire’s 26 hospitals have a variety of different systems, different levels of electronic records, and different vendors.

“People are taking different approaches with the systems they have. They are trying to do more in real time,” Diefendorf said. As to trigger tool analysis, Diefendorf said it is resource intensive and expensive.

And while New Hampshire’s hospitals still have work to be done, they are making progress in finding and implementing improvements, she said. For instance, hospitals are working to change the culture of reporting by making it clear that staff needs to speak up when problems arise.

Hospital leaders go on rounds with medical personnel and hold “safety huddles” in which the entire senior executive team comes to real-time discussions about what’s going on, Diefendorf said.

Having the top executives listening on a daily basis changes the dynamics on accountability, she said, which wouldn’t have happened a couple of years ago.

“Having the CEO look you in the eyes saying ‘we want to know’ is an approach that is long overdue,” Diefendorf said. “What they hear, they have to act on.”

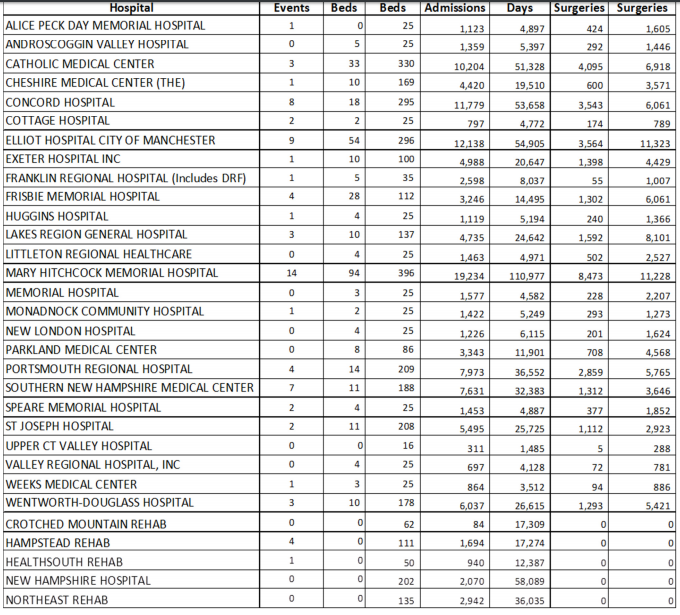

Below, find the 2014 list of adverse events by hospital with information about hospital activity.

Department of Health and Human Services

2014 NH Adverse Events per organization bed, capacity and activity.