Arnie Alpert spent decades as a community organizer/educator in NH movements for social justice and peace. Officially retired since 2020, he keeps his hands (and feet) in the activist world while writing about past and present social movements.

By Arnie Alpert, Active with the Activists

PORTSMOUTH—Nur Shoop remembers meeting Valerie Cunningham for the first time about fifteen years ago at a meeting of the Seacoast NAACP. Shoop asked Cunningham to sign her copy of Black Portsmouth, a book Cunningham had co-authored based on decades of historical research.

By then, Cunningham’s work had already led to the creation of the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail, which marked sites where the city’s first Black residents lived and worked. From its birth with a map and brochure for self-guided walking tours, the Trail had evolved into a nonprofit organization a staff of six, an active board, and a team of volunteer tour guides taking groups through the city’s oldest neighborhoods. At each stop, tour leaders would tell stories of African people who had been enslaved and brought to Portsmouth as far back as 1645.

A year or two after they met, Shoop said, Cunningham “asked me to help her with tours. And who can say no to Valerie Cunningham?” Now, Shoop is the lead tour guide, a volunteer position with the group now known as the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire.

Thursday, marking its thirtieth anniversary, the organization celebrated Cunningham’s leadership at the Portsmouth Historical Society, which occupies the former site of the local library.

It was there that the story started, in a sense, when in the late 1950s the teenage Valerie Cunningham started a quest to uncover the stories of Portsmouth’s first Black residents. As the Trail’s Executive Director, JerriAnne Boggis, put it, “she was searching for the reflections of herself on the pages of every book the library had to offer.”

In the library’s collection, she found only hints of the Black people who had lived and been enslaved in colonial Portsmouth, but she kept searching. In a city which has long prided itself on its heritage, Cunningham uncovered details of the city’s history that had been too long ignored.

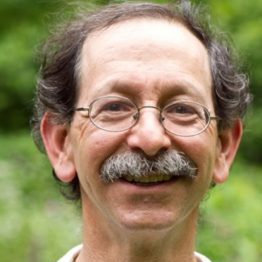

Mark Sammons, who later became her research partner, said the door opened when she began looking at centuries-old church archives from 1807 and found a record of a $1 Christmas season donation to “Venus, a black.” “That was sort of a Eureka moment for her,” he said. As Sammons told it, she just kept “looking and looking and looking until her living room was filled with photocopies of historic documents.”

When she began, racial exclusion was still commonly practiced in New Hampshire’s restaurants, hotels, rental properties, and other businesses. After high school, Cunningham married and moved away, returning to Portsmouth in the late 1960s. By then, Black consciousness was gathering steam and Black history was gaining attention. Cunningham joined activist groups, but did research on her own.

The research became her passion, pursued quietly for decades. Without academic training or credentials, and well before the internet opened up previously unimaginable avenues for research, Cunningham learned how to find and reveal the details of people long dead. What were their names? Where did they live? What work did they do? How did they organize themselves? In her files and in her mind, characters from her city’s past came alive.

At a meeting of a “Diversity Committee” sponsored by a local foundation in the early 1990s, “it occurred to me one day that I should tell them more about the work that I was doing,” Cunningham said, in a recording played at the anniversary event. “Everybody kind of knew that I was doing something about Black history. They thought, wow, this is really very interesting. We should get this available to the teachers so they can talk about it to their students and classes.”

With the committee’s encouragement, Cunningham teamed up with Sammons, a historian working at the Strawbery Banke museum. Together they wrote and edited the stories Cunningham had researched, put them in a binder for distribution to teachers, and created a brochure with a map for self-guided walking tours. Cunningham also established the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail as a nonprofit organization so they could raise money and install plaques marking significant sites. With the map, the brochure, and the plaques, the newly formed Heritage Trail brought Portsmouth’s Black history out of Cunningham’s files and into the light of day. The binder’s contents grew, too, and became Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage, published by Cunningham and Sammons in 2004.

Thirty years after the formal part of the project began, the stories of Portsmouth’s first Black residents “now form an integral part of our collective history and identity in New Hampshire,” said Shari Robinson, the Black Heritage Trail’s president. “Valerie’s work has been nothing short of transformative. Through her dedication, she has provided a voice to those who were long silenced, and she has ensured that the history of the Black lives in New Hampshire is recognized, respected and remembered.”

Mark Sammons, now retired and living in Tucson, flew in for the occasion. “She asked me very quietly once if I’d help with a pocket brochure. And of course, before I know it, I’m enthusiastically volunteering for 10 years, or life, whichever is longer,” he recalled with a smile. “Everyone she touches seems to become engaged.”

Kirby Randolph, Cunningham’s daughter, flew in from Kansas City, where she teaches in the Department of the History and Philosophy of Medicine at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Her mom was shy, she said, but busy. “I just remember, Mom always had some meeting to go to, and the phone was ringing, and people always wanted a little information about this and a little information about that.”

Cunningham always talked about Portsmouth’s Black history at home, Randolph said, and now, thanks to her mom’s work, “I think it’s probably going to be better and easier for the Black girls in Portsmouth.”

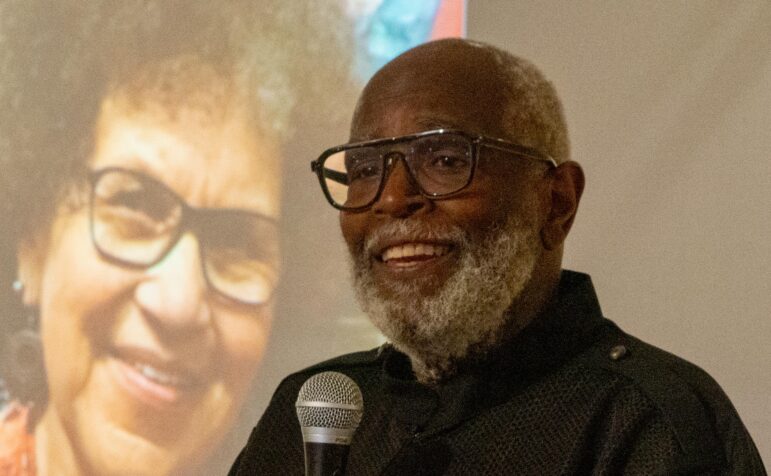

Valerie Cunningham wasn’t present to hear the flow of accolades. On her way to the event, she tripped, broke her wrist, and spent the rest of the evening at the hospital. So, she missed hearing Portsmouth Mayor Deaglan MacEachern read a proclamation declaring it Valerie Cunnigham Day. She missed hearing letters read from Jeanne Shaheen, Maggie Hassan, and Chris Pappas. She missed watching her daughter tear up with emotion. And she missed spending a couple hours with a roomful of friends and admirers.

Above, Portsmouth Mayor Deaglan McEachern is pictured with Kirby Randolph, Valerie Cunningham’s daughter at Thursday night’s celebration with the plaque honoring Valerie Cunningham. ARNIE ALPERT photo

She would have been surprised by the unveiling of the latest NH Black Heritage plaque, soon to be located in Portsmouth’s old South End. At the top it says, “Valerie Cunningham (b. 1942).” It goes on, “Cultural historian, activist, and mentor Valerie Cunningham was born in Portsmouth. Her painstaking research recovered and celebrated the stories of Black life in Portsmouth and beyond.” “By centering Portsmouth’s Black residents, Cunningham’s work became a model for public historians,” the plaque also says.

Had she been there, she might have been embarrassed with all the fuss, attention she might prefer were going to the stories of Prince Whipple, Ona Judge Staines, and generations of Black Portsmouth residents who lived lives of dignity in spite of all the obstacles placed before them. But I know she’s pleased and proud of how far the Black Heritage Trail has come since it began with a binder and a brochure. The Trail leads regular walking tours in Portsmouth, holds annual events marking Juneteenth, sponsors the annual Black New England conference, and holds “tea talks” on a wide variety of topics. In addition to the African Burial Ground and markers at historic sites in Portsmouth, there are now Black History markers in Kittery, Windham, Warner, Milford, Andover, Derry, Hancock, Dover, Jaffrey, and Nashua. The next one, honoring enslaved people’s contributions to Manchester’s textile industry, will be dedicated on September 21.

At the Thursday night celebration, Rev. Robert Thompson was the final speaker and singer. He recalled a meeting with Cunningham at this church office in Exeter years ago. “I knew that whatever she was about to ask me, it was clear she was going to ask me something, that the answer was going to be ‘yes,’” he said. What she asked was for Thompson to take a seat on the board of the Portsmouth Historical Society, where he could make sure connections with the Black Heritage Trail were as strong as possible. Later she asked him to join the Trail’s board and serve as its president. “I couldn’t say no to Valerie,” he said. “I don’t know if you can. I couldn’t.”

For the anniversary, his friend Valerie asked him to sing her favorite song, John Lennon’s “Imagine.” With Rev. Thompson’s stirring voice ringing out, and Cunningham across town at the hospital, the celebration reached its conclusion.

Keeping the Trail’s work going and growing takes money, of course, and the anniversary celebration didn’t neglect the topic. In addition to a Valerie Cunningham marker, they unveiled the Valerie Cunningham Society for the Preservation of African American History, a campaign aiming to raise $400,000 to transform the Trail into a high tech “Outdoor Museum.”

Maryellen Burke delivered the fundraising pitch prior to Rev. Thompson’s song. The Black Heritage Trail of NH is a beacon, she said, with an impact that can ripple through New Hampshire and beyond. “This isn’t about the past, folks. This is about the future, a future where our shared history is not just remembered but celebrated, and a future where racial anxieties and misunderstandings become a thing in the past.”

Imagine.