Power to the People is a column by DONALD M. KREIS, New Hampshire’s Consumer Advocate. Kreis and his staff of four represent the interests of residential utility customers before the NH Public Utilities Commission and elsewhere.

‘Twas the night before Christmas – and our electricity grid was in trouble.

Many will recall December 24, 2022 as miserable – temperatures plunged and a winter storm that blew through had caused massive outages that utility crews were scrambling to correct.

Thousands of Granite Staters now know what it is like to have a Christmas eve, and a Christmas, without electricity.

I was among the lucky ones, spending the holiday with relatives in Bennington, Vermont. We had plenty of power and in due course Santa arrived as usual (or so it appeared).

But, as I said, I was with relatives. A distraction or two is always a helpful option in such circumstances, so as night fell on the evening of December 24, I found myself firing up the ISO New England app on my mobile phone. ISO New England is the nonprofit that runs the region’s bulk power system.

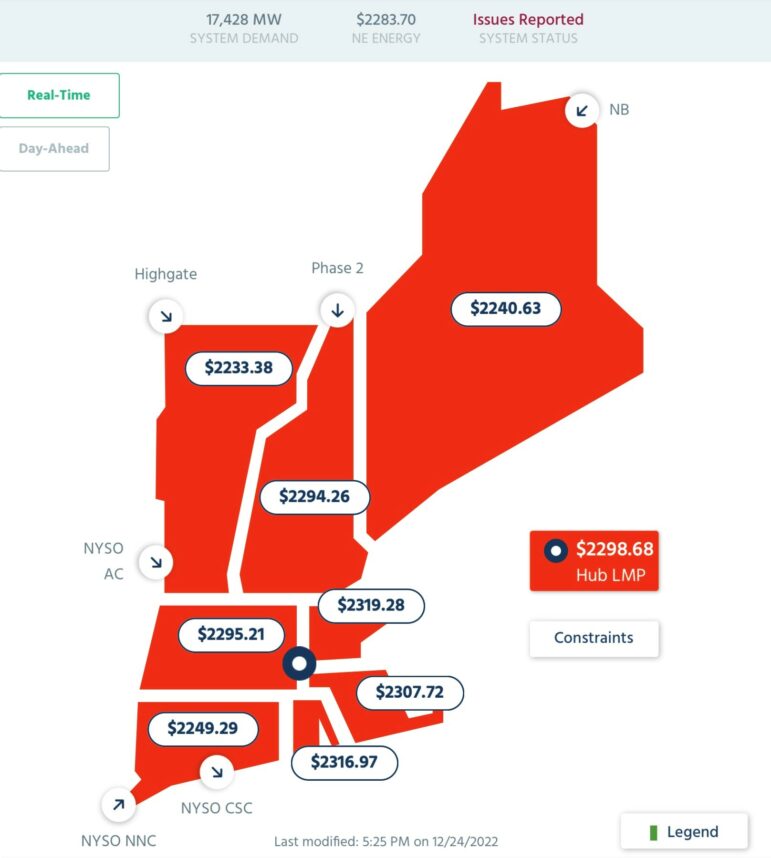

I looked at the regional map and I saw red, literally. A tribute to Santa Claus? Anything but.

The map shows real-time wholesale electricity prices around New England at 5:25 p.m. New Hampshire’s price was $2,294.26 per megawatt-hour. To put that in perspective, it’s the equivalent of $2.29 per kilowatt-hour, and Granite Staters have been justifiably howling with outrage over default energy service charges in the range of 20 to 26 cents per kilowatt-hour.

The good news is that no residential customers in New Hampshire paid these absurdly high prices. They lasted from about 4:30 to 6:00 p.m., right when dusk fell and the day’s peak demand occurred (on schedule), but retail rates were firmly locked in.

Here’s two reasons why you should care about this series of unfortunate events anyway.

First, stratospheric wholesale prices like these do have an effect on retail rates. Real-time price volatility is a major reason why wholesale suppliers have forced Eversource, Unitil, and Liberty to charge such high rates for default energy service – or, at least, we can say that about those few wholesale suppliers which still condescend to submit bids to our utilities.

Second, when real-time prices soar to these heights it means something is wrong with the bulk power transmission system and there is danger of rolling blackouts or, worse, an uncontrolled system failure.

In fact, a big regional grid operator to our west, PJM, did impose rolling blackouts in the face of this arctic blast that affected much of the continent.

Wholesale producers in New England are not allowed to submit bids to provide real-time energy higher than $2,000. So, when the market price exceeds $2,000 it means that some generators that promised to produce power are not, in fact, doing so.

The additional money above $2,000 pays for reserve generators that had to be pressed into service unexpectedly. Something very similar happened during the 5:00 p.m. hour on Labor Day back in September 2018.

The Labor Day 2018 wholesale fiasco and the Christmas Eve wholesale debacle had at least two things in common. In both instances, the weather turned out to be worse than forecast and so demand was higher than what was predicted by ISO New England.

More intriguingly, another thing these two situations had in common is that Mystic Station just north of Boston – the region’s biggest generator, relying on liquified natural gas that arrives by sea – produced no electricity.

In 2018, Mystic Station experienced an unexpected outage. I don’t know if that’s what happened this time, but I do know that New England is paying a huge federally approved premium to this facility – so-called RMR (“reliability must run”) payments – to keep it in business this winter and next.

Mystic Station is owned by Constellation, one of the region’s two major producers of wholesale electricity. (The other is NextEra, owner of the Seabrook nuclear power plant, which operated without incident.) I’d say Constellation has some explaining to do.

So does ISO New England. But, beyond a possible need for better meteorology, the regional grid operator actually did a pretty good job of managing the crisis. Though demand for electricity was higher than predicted on December 24, ISO New England was right on target with its load forecast for the peak hour of 5-6 p.m.

Some people have asked me why ISO New England did not request that customers curtail their use of electricity. The answer is that the grid operator implemented its emergency procedure for such situations (known in ISO-New England-speak as “OP4”) and, working through the list of OP4 measures, the control room was just one step away from issuing such a public call for conservation.

In my view, we should be grateful it did not come to that. After all, it was Christmas Eve and there was already enough electricity-related misery across the realm.

One final point: Though our region is generally over-reliant on natural gas to produce electricity, there were very few gas generators running on December 24. These generators typically don’t buy “firm” natural gas capacity, and when it’s bitter cold any gas available to purchase is diverted to heating customers.

Interestingly, there was only 100 megawatts of coal-fired generation running on Christmas Eve. That means at least one of the units at Merrimack Station was idle.

Why? I have no idea. Availability to supply peaking power is supposedly the reason we make the capacity payments to Merrimack Station that keep the place in business even though it seldom runs.

Generators fired by fuel oil, along with wind and hydro facilities, are what saved the day. Reliance on fuel oil is problematic, not just because burning it to make electricity causes air pollution but because it must be trucked in and has thus a tendency to run out.

Will we, in fact, run out? Well, ISO New England’s 21-day forecast, issued on January 3, says everything is normal. But we have just been reminded, thanks to a scary Christmas Eve, that forecasts are not infallible.