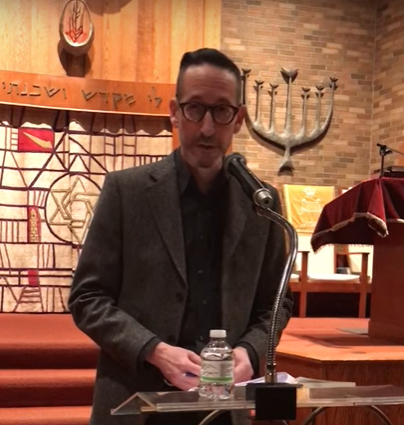

By MICHAEL DAVIDOW, Radio Free New Hampshire

My favorite newspaper, the New York Times, which is still worth reading in spite of itself (sort of like how a cereal box still lists ingredients, no matter what other useless verbiage it might also feature), ran an interesting obituary the other day, and got some facts wrong in doing so. Andrei Gromyko, the late Soviet ambassador, used to say that the Times was a very balanced newspaper: half truth and half lies. Often, however, it’s just plain tone deaf. Too busy with its own agenda.

The obituary concerned a Soviet filmmaker named Marina Goldovskaya, and if that is not a lovely name, I don’t know what would be. The subjects of her documentaries were things like the gulag, the role of journalists in a free society, the worth of the old aristocracy. Her work was controversial and she often risked being punished for it. She seems to have been a great soul with very little fear; or more precisely, she mastered her fears.

The Times ignored her Jewish heritage, of course, because the Times is always happy to write Jews out of history. But of equal note on this occasion, they ignored something else too: a poem of life hiding in plain sight, made from the bitter iron and ugly steel of old Soviet reality, shot through with the brilliant light of pure human decency.

Per the Times, “in 1938, her father, then a deputy minister of film, had been overseeing construction of the Kremlin’s movie theater when a lamp exploded. Stalin believed it was an assassination attempt and sentenced him to five months in prison.”

Something about that sentence stuck me as odd. As I sometimes mention in these pages, I am a criminal defense attorney by trade, and “five months in prison” seemed like an unlikely punishment to me. People are usually sentenced to even numbers: a year, or half a year, or (especially in the old Soviet Union) ten years, or life, or death. You also did not get “five months” for trying to kill Stalin. So I looked things up on line. And conveniently enough, it turns out that this woman wrote an autobiography that was readily available, in which she tells the story a little differently.

Her father, surnamed Goldovsky, had been arrested, imprisoned, and duly tortured because of that exploding lamp (the Times got that right, at least). They tried to make him confess his crime, but he refused. They brought him for yet another interrogation and there he was made to face his accuser in person, a co-worker at the Kremlin named Shumyatsky.

Shumyatsky had also been tortured for months, and he had plainly broken under the strain. This pale ghost of a man rambled on about Goldovsky’s guilt until Goldovsky finally snapped. He yelled at his old friend, asserted his innocence, and told him he was only hurting himself by saying such blatant lies. Shumyatsky, stunned, continued to mumble that Goldovsky was guilty. And the interrogation was over. Goldovsky was returned to his cell.

Shortly after that happened, though, he was also simply released. He had not been “sentenced to five months.” They simply let him go after that staged encounter of his with Shumyatsky, and they told him to keep his mouth shut. And decades later, after the KGB opened its files, and people were more able to get answers to things, his daughter learned why: an hour after that encounter, Shumyatsky had asked to give his captors another statement, in which he had sworn that Goldovsky was, in truth, an innocent man. Shumyatsky himself was executed. But in a final act of humanity, a final nod to the value of truth, a final statement of grace, he had saved Goldovsky’s life.

That was the story that the New York Times managed to muff. Just another dime-common number about truth, and life, and death. Russian-style, mixed with a touch of Judaism: these are my people, after all, so unlike those writers and editors in Manhattan, I feel these things pretty keenly.

The Jewish holiday of Passover is coming soon, anyway. For those unfamiliar with it, Passover celebrates the liberation of the ancient Israelites from captivity in Egypt. They will be celebrating it in Ukraine this year, under bombardment from liars, bullies, and those lacking shame. It’s only fitting, though. We teach that we were liberated not because we were powerful, but because we worshipped the truth. Never an easy thing to do.

He is the author of Gate City, Split Thirty, and The Rocketdyne Commission, three novels about politics and advertising which, taken together, form The Henry Bell Project, The Book of Order, and his most recent one, The Hunter of Talyashevka . They are available on Amazon and Barnes and Noble.