By Nancy West, InDepthNH.org

Some New Hampshire police chiefs have been purging disciplinary records from officers’ personnel files for years, raising new questions about whether the secret “Laurie List” – even in its latest May revision – is protecting the constitutional rights of criminal defendants to all favorable evidence.

This revelation may be in conflict with the attorney general’s longstanding policy that requires police chiefs to review personnel files to determine which officers belong on the Laurie List that includes dishonest members of law enforcement, then alert prosecutors.

The widespread practice was hiding in plain sight in police union collective bargaining agreements that say discipline can be purged after time frames ranging from 12 months to seven years at the chief’s discretion, depending on the department and the severity of the officer’s infraction.

Attorney General Gordon MacDonald declined requests for an interview about the routine purging of police personnel files, but Senior Assistant Attorney General Lisa Wolford responded with a brief email.

“This has been brought to our attention and we are reviewing it,” Wolford wrote, declining further comment.

Why Laurie

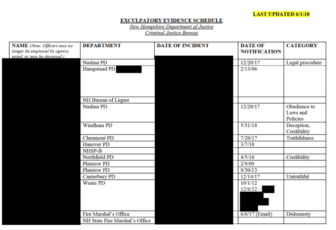

The  June 1, 2018 Exculpatory Evidence Schedule One of eight pages including 171 redacted names of law enforcement officers with credibility issues.[/caption]

June 1, 2018 Exculpatory Evidence Schedule One of eight pages including 171 redacted names of law enforcement officers with credibility issues.[/caption]

“Defense attorneys don’t have access to the Laurie List,” Bissonette said in an interview, adding there is no way to verify that prosecutors are checking the list or that police chiefs aren’t purging serious discipline from personnel files.

They are left to trust in the system that Bissonnette believes is broken.

“We don’t think that’s sufficient,” Bissonnette said.

Common practice

InDepthNH.org reviewed a number of current police union contracts and found purging language in collective bargaining agreements in departments across the state that among others, included Claremont, Dover, and Salem. Collective bargaining agreements can be reviewed at the Public Employee Labor Relations Board website.

The purging language in Manchester’s and Nashua’s patrolman’s contracts dates back to 2004 after a memorandum was issued by former Attorney General Peter Heed. The Heed memo detailed the importance of providing the police discipline to defendants and explained what might constitute exculpatory evidence, including evidence of police dishonesty.

The Manchester patrolman’s contract says nothing can be removed from a personnel folder except by mutual agreement of the officer and police chief. Otherwise all written reprimands shall be removed from the officer’s personnel folder after 12 months if the employee has satisfactorily corrected the nature of the reprimand.

Manchester Police Chief Carlo Capano didn’t respond to a request for an interview.

Nashua’s purge

The current Nashua patrolman’s contract says purging disciplinary documents from an officer’s personnel file is done at the sole discretion of the police chief after five years if the officer requests a review. Otherwise “stale disciplinary documentation” will be purged after seven years. It makes no distinction between serious or lesser discipline such as tardiness.

Nashua’s proposed collective bargaining agreement spells out time frames for purging and details the kinds of infractions that can be removed, but for the first time makes clear that any discipline that would be considered exculpatory evidence or Laurie matters can never be removed.

“The proposed agreement’s provisions allowing for the purging of police personnel files are deeply problematic and must be eliminated, even in instances where the material to be purged does not warrant placement on the Exculpatory Evidence Schedule,” Bissonnette wrote in a letter to Nashua officials on Friday.

Deputy Nashua Police Chief Michael Carignan said the changes in the proposed contract will likely be adopted. He said they will be totally in compliance with MacDonald’s directives. Of the 14 names on Nashua’s Laurie List, only two are still working as police officers, he said, adding the rest have died, retired or been terminated.

Carignan said even if serious discipline was removed from a personnel file in the past, it would likely remain on a permanent database if it involved an internal investigation. It would also show up on personnel evaluations, he said.

Steven Bolton, Nashua’s corporate counsel, said there is no such thing as a perfect way to guarantee all exculpatory evidence involving police is turned over to the defense.

“The important thing to know is the contract that’s currently proposed provides for the first time that if a matter had gotten an officer placed on Exculpatory Evidence Schedule, the reports and documents relating to that incident can never be purged unless the officer is removed from the EES,” Bolton said.

“This new contract complies with the attorney general’s memorandum and directive to police departments to preserve records and documents of the incident that led to officer to be placed on EES,” Bolton said.

MacDonald’s Update

Attorney General MacDonald updated Laurie protocols in May, fulfilling a campaign promise made by Gov. Chris Sununu to provide due process rights to police officers seeking a way off the list.

MacDonald released the update at a joint news conference with Sununu and representatives of police departments and unions on hand. Defense attorneys were not invited to the news conference or to the table when the protocol was being rewritten.

Three unidentified officers’ names have already been removed from the Laurie List since MacDonald’s update.

Police say inclusion on the list can ruin their career. Every time they testify, their Laurie issue is raised, although it is up to a judge to decide if it should be brought up at trial. Officers complain that they will not be promoted or offered certain positions because of being on the list.

Some officers believe that inclusion on the list can be politically motivated if the chief simply doesn’t like you.

Always controversial

The Laurie List has been controversial since the public first learned in 2012 that it was kept, that law enforcement names on the list are secret and the process used to determine whether the name should be disclosed to a defendant is also highly confidential.

When news reporters first asked questions about the list six years ago, some county prosecutors wouldn’t even admit a Laurie List was kept for fear of breaching confidentiality, and some didn’t appear to know it was their responsibility to make sure the relevant police disciplinary information was turned over to the defense.

Since then, the list has become a political priority. Attempts by lawmakers to help police get their names removed from the list were unsuccessful in two sessions of the legislature.

The most recent Laurie List dated June 1 obtained by InDepthNH.org contained 171 redacted names.

The new protocols make it clear that an officer’s name is placed on the list only after sustained discipline involving dishonesty, excessive force or mental instability.

While some believe the names on the Laurie List should be public, police officers have maintained that they weren’t getting due process by being placed on the list with no way to have it removed.

Former Attorney General Joseph Foster updated the Heed memo March 17, 2017. He explained the 1963 landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Brady v. Maryland that established the obligation of a prosecutor to provide potentially exculpatory evidence to the defense.

“Exculpatory evidence is evidence that is favorable to the accused. This includes evidence that is material to the guilt, innocence, or punishment of the accused or that may impact the credibility of a government witness, including some police discipline,” Foster wrote.

Laurie expert

Concord attorney Jim Moir, the state’s leading expert on Laurie issues, said as new revelations occur about the Laurie process, there is simply no way of knowing if defendants are getting their right to all favorable evidence, including police dishonesty, because of the secrecy.

“It doesn’t surprise me,” Moir said of the purging by police chiefs.“That’s the problem. We don’t know. It’s a black box and we can’t see inside,” Moir said. “It’s just weird.”

Over the years, the attorney general’s office has insisted that police personnel files are confidential and said releasing the names of the officers on the list would violate their privacy rights.

ACLU-NH’s Bissonnette disagreed.

“The public interest in disclosure here is not just significant, it’s monumental,” Bissonnette said.

“Any privacy interest that exists here is minimal when we are talking about public servants who are being paid by taxpayer dollars in cases in which there have been sustained findings of police misconduct warranting placement on the list. There’s no basis to withhold that information from the public.”

Three Unidentified Officers Removed from Secret ‘Laurie List’ Under New Protocol