By ARNIE ALPERT, for InDepthNH.org

Two years after Martin Luther King’s birthday was first observed as a national holiday in 1986 and most other states going along, New Hampshire was a holdout. With the state legislature rejecting bills to establish a state holiday named for Dr. King session after session, local school boards, which controlled their own calendars, were starting to localize the issue.

For Vanessa Johnson, a proposal to put King Day on the calendar for school holidays was not a surprising way for her tenure to begin. She was not only the first Black person elected to the school board; she was also the daughter of Lionel W. Johnson, the city’s most prominent civil rights activist.

But the proposal’s passage caught the editors of the city’s newspaper by surprise. Accustomed to dominating local politics even more than they did at the state level, the Manchester Union Leader’s publisher and editorial page director teamed up with a conservative member of the school board to push a proposal to rescind the school holiday. In the next few weeks, a series of editorials, some on the front page, labelled King a “political demagogue,” argued that the school board’s move was “undemocratic and improper,” blasted King for associations with people identified as Communists, and asserted that King’s role in the movement against the U.S. war in Vietnam rendered him undeserving of honor denied to other important historic figures.

With a motion to reverse course on its agenda, the school board agreed to hold a public hearing and vote again. The Union Leader used its editorial page much as advocacy groups now use their web sites and social media, informing readers about the time and place of the hearing, providing talking points, and listing the names and phone numbers of school board members. Despite their efforts, the motion for reconsideration was defeated. Martin Luther King Day would be a school holiday in Manchester. The Union Leader then stepped up its efforts to keep the Granite State free from a state holiday honoring Dr. King. In that, they were successful for another decade.

At the time of the Manchester school board kerfuffle, I was the American Friends Service Committee’s New Hampshire Program Director and served as communications coordinator of a new, concerted effort to win passage of a state holiday named for Dr. King. It became my daily practice to stop at a local newsstand each morning and peek at the Manchester paper. Without needing to buy a copy, I could scan the front and the editorial page, which was always printed at the front of the second section. But when they ran editorials blasting the King Day proposals, I purchased the paper so I could clip and file them.

My file soon became quite thick. From early October 1988 and late May 1991, the Union Leader and its Sunday edition, the NH Sunday News, published 100 editorials, op-ed columns, and editorial cartoons dealing in some way with Martin Luther King and why New Hampshire should not have holidays named for him. Most of the editorials were the work of Jim Finnegan, the chief editorial writer. Out of Finnegan’s 70 signed columns opposing King Day, more than half dealt largely with Dr. King’s anti-war stance.

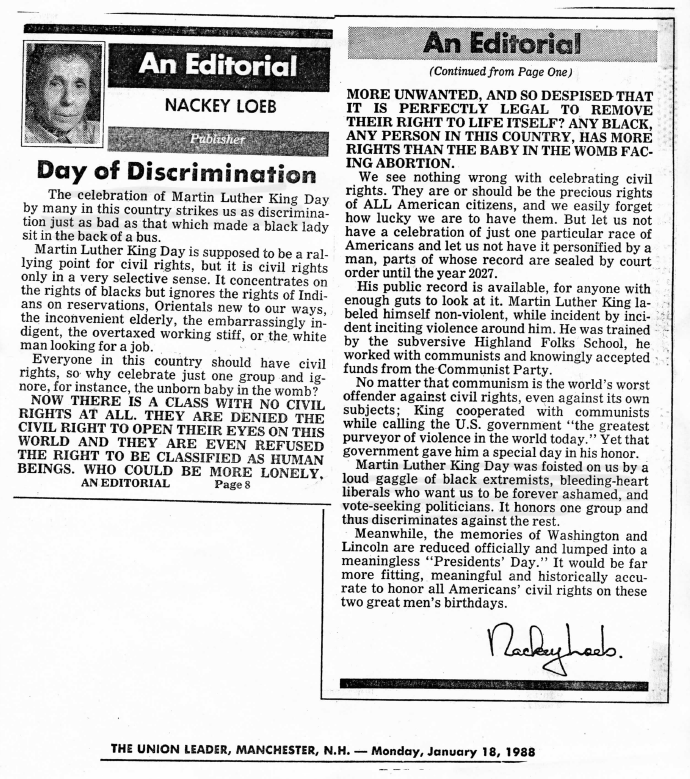

Five of the editorials from the period were signed by Nackey Loeb, the paper’s publisher, who had been at the paper’s helm since the death of her husband, William Loeb, in 1981.

If you don’t remember William Loeb, think of Donald Trump with a daily newspaper instead of a Twitter account. Loeb’s editorials, often on the front page, used capital letters for emphasis and were known for the insulting nicknames he gave his political foes, of whom there were many. His views hewed to the far-right, for example defending Senator Joseph McCarthy and enforcing ax-the-tax politics. For Loeb, the newspaper was a bully pulpit with the emphasis on bully. With New Hampshire playing its historic role as home of the first-in-the-nation presidential primary, William Loeb’s politics exerted an influence far beyond what might be expected from the daily paper of a small New England city.

Nackey Loeb seemed to work in her late husband’s shadow from the time she assumed control. But that shadow has been removed thanks to Meg Heckman’s new biography, Political Godmother: Nackey Scripps Loeb and the Newspaper that Shook the Republican Party. After a close study of the Union Leader in the years of Nackey Loeb’s leadership, including some 1600 editorials that appeared over her name, Heckman concludes that while the wife may have been less prone to use of personal insults than the husband, her politics were every bit as right wing.

“Inflammatory editorials had been William Loeb’s main calling card,” Heckman writes, “so comparisons between his work and hers were incessant. Nackey explained repeatedly that although she had a different voice and style, she shared her late husband’s archconservative views. ‘Somebody once said he used a sword and I used a needle,’ she said in an interview. ‘But we were both aiming for the same target.’“ Her “public debut” as a right-wing pundit, according to Heckman, was a 1954 defense of Senator Joseph McCarthy from an attack by her newspaper publisher brother, Charles E. Scripps.

After becoming the Union Leader’s publisher, says Heckman, Mrs. Loeb initially copied her husband’s style, but later she developed her own, with her needle poking at taxes, big government, communism, homosexuality, feminism, the United Nations, and of course, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and any effort to give him special honor.

One front-page editorial, dated January 18, 1988, begins, “The celebration of Martin Luther King Day by many in this country strikes us a discrimination just as bad as that which made a black lady sit in the back of a bus.” With the usual mix of all-caps and regular type, Nackey Loeb asserted that King had been trained by the Highland (sic) Folk School, knowingly accepted funds from the Communist Party, and incited violence. His holiday, she said, “was foisted on us by a loud gaggle of black extremists, bleeding-heart liberals who want us to be forever ashamed, and vote-seeking politicians.”

The paper’s opposition to the King holiday should not be separated from its hostility to civil rights and active defense of segregation. An important element often left out of treatments of the Union Leader but revealed by Heckman is the long connection between the Loebs and the Citizens Council, a white supremacist group formed after the U.S. Supreme Court decreed school desegregation illegal in Brown vs Board of Education. Their relationship, which lasted into the 1980s, apparently began when the Union Leader published a cartoon drawn by Nackey Loeb decrying the use of federal troops to protect the Little Rock Nine, black students who enrolled in the previously all-white Little Rock High School. Her cartoon was reprinted in The Citizen, the magazine published by the Citizens Council. They printed it again in 1972, when William Loeb spoke at their leadership training institute, and again in 1981 with a tribute to William Loeb when the publisher died.

As late as 1983, The Citizen published a story praising Nackey Loeb, which drew an appreciative letter to the editor from the Union Leader’s new publisher. Heckman found appreciative letters to Nackey Loeb dated 1987 from the Council of Conservative Citizens, an offshoot of the Citizens Council formed two years earlier (and which still exists).

Heckman sees the Loebs’ alliance with white supremacists as part of a strategy to build their national influence on the GOP right flank. Loeb did serve as chairman of the Coordinating Committee for Fundamental American Freedoms, a lobbying group created by the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission to block civil rights legislation and nationalize support for Jim Crow. Calling white supremacy “a southern cause,” Heckman writes, “William Loeb saw supporting segregationists as a strategic move that might benefit conservatives” by driving away African Americans and turning the GOP into “the white man’s party.” As vile as that sounds, it might be too kind.

New Hampshire in the 1960s was not the bastion of civil rights we might wish to remember. Housing segregation was openly practiced and the state’s grand hotels openly barred Blacks and Jews from staying there. Segregation had a defender running the state’s dominant newspaper.

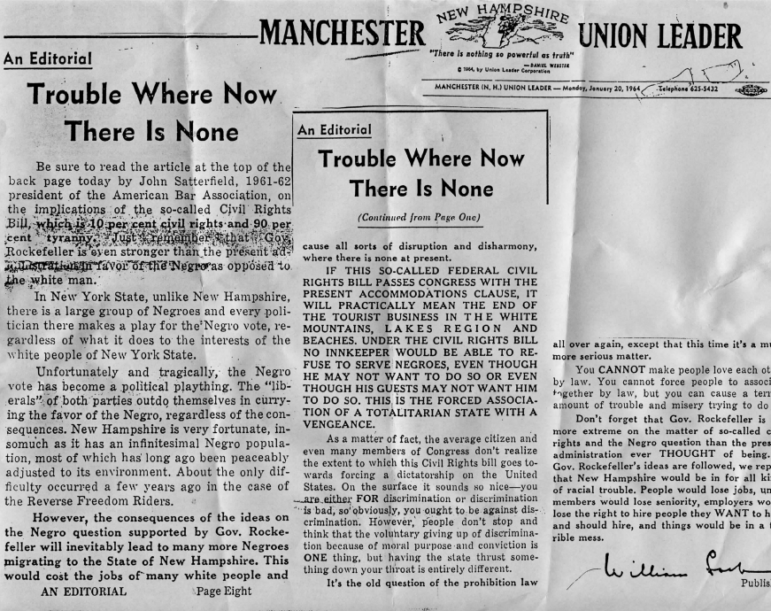

Writing in 1964, while Congress was debating the Civil Rights Act barring discrimination in public accommodations, William Loeb published an editorial titled, “Trouble Where Now There is None.” Starting on page one, with the mix of all-caps and normal type, the publisher asserted that passage of the Civil Rights Act “WILL PRACTICALLY MEAN THE END OF THE TOURIST BUSINESS IN THE WHITE MOUNTAINS, LAKES REGION AND BEACHES,” since no innkeeper would be able to deny service to Blacks. In other words, segregation was a northern practice and its defense was a northern cause, too.

After Manchester’s adoption of a school holiday in honor of Dr. King in 1988, attention returned to the State House while a succession of other districts added the King holiday to their school calendars. A 1989 bill to establish MLK Day in place of Fast Day, an anachronistic holiday supposedly honoring a colonial era governor, was the first to draw a large crowd of supporters to the State House. In addition to civil rights groups like the NAACP, the proposal drew support from the NH AFL-CIO, the NH Council of Churches, the state’s largest teachers and public employee unions, and Digital Equipment Corporation, then the state’s largest manufacturing employer. With the Union Leader still in opposition as well as Governor Judd Gregg, the King Day bill failed just as previous proposals had going back to 1979. It would take another decade before New Hampshire would name a day for Martin Luther King, Jr. It was the last state to do so. (Background and a chronology of the 20-year campaign for MLK Day in New Hampshire can be found here.)

In the Union Leader’s heyday, it was the state’s only morning newspaper and the only one which circulated statewide, factors which made it possible for the Loebs’ editorial opinions to have such influence. As broadcast media grew in importance, as regional dailies shifted to morning distribution, and as the internet made it possible for readers to get news from anywhere and everywhere, the Union Leader’s influence waned.

But it could be said that the Loeb style of inflammatory editorializing coupled with white supremacist advocacy lived on, well after Nackey Loeb died and passed control of the paper to Joe McQuaid, the son of one of her husband’s top associates. As Meg Heckman describes, Nackey Loeb deserves credit – or blame – for the rise of Patrick Buchanan as an electoral force, first encouraging him to challenge an incumbent president after George H. W. Bush signed the 1991 Civil Rights Act. After losing to Bush in 1992, Buchanan ran again four years later, still with the strong backing of Nackey Loeb. Buchanan’s campaigns will be remembered for nativist, homophobic, and “America First” stances consistent with those of the Loebs and later with Donald Trump.

“Nackey didn’t create right-wing populism,” writes Meg Heckman, “but she played a crucial role in amplifying aspects of its message and connecting its adherents, hinting at the power and divisive rhetoric that results when fellow travelers find new ways to interact with each other.”

“Her sprawling audience of malcontents helps explain the deep roots of the antiestablishment enthusiasm that propelled Trump to the White House,” she adds.

As for Donald Trump, whose racist, megalomaniacal approach has William Loeb as a progenitor, he is out of favor at the Manchester daily. Pat Buchanan’s Trumpist editorials still occupy prominent real estate on the op-ed page, but the current leadership of the Union Leader favors anti-Trump conservative voices such as Mona Charen, George Will, and Jennifer Horn, a former state GOP chairwoman in the leadership of the anti-Trump Lincoln Project. The days of page one editorials using ALL CAPS for emphasis are gone. If you want that style of rhetoric, you’ll be better off on Twitter.

Meg Heckman, Political Godmother: Nackey Scripps Loeb and the Newspaper that Shook the Republican Party, Potomac Books, 2020.

Arnie Alpert lives in Canterbury and blogs at inzanetimes.wordpress.com. His columns have appeared in many New Hampshire newspapers, including the Union Leader.