Arnie Alpert spent decades as a community organizer/educator in NH movements for social justice and peace. Officially retired since 2020, he keeps his hands (and feet) in the activist world while writing about past and present social movements.

By Arnie Alpert, Active with the Activists

For two weeks in the spring of 1977, New Hampshire was at the center of national attention. No, it had nothing to do with the first-in-the-nation primary. The matter that grabbed headlines was the arrest of 1415 people who had peacefully taken over the construction site of a proposed nuclear power plant in Seabrook. After being taken away on buses and National Guard trucks and processed at the Portsmouth Armory, the protesters were delivered to four other armories, where, refusing to pay bail, they engaged in a battle of wills with the stubbornly pro-nuclear governor, Meldrim Thomson.

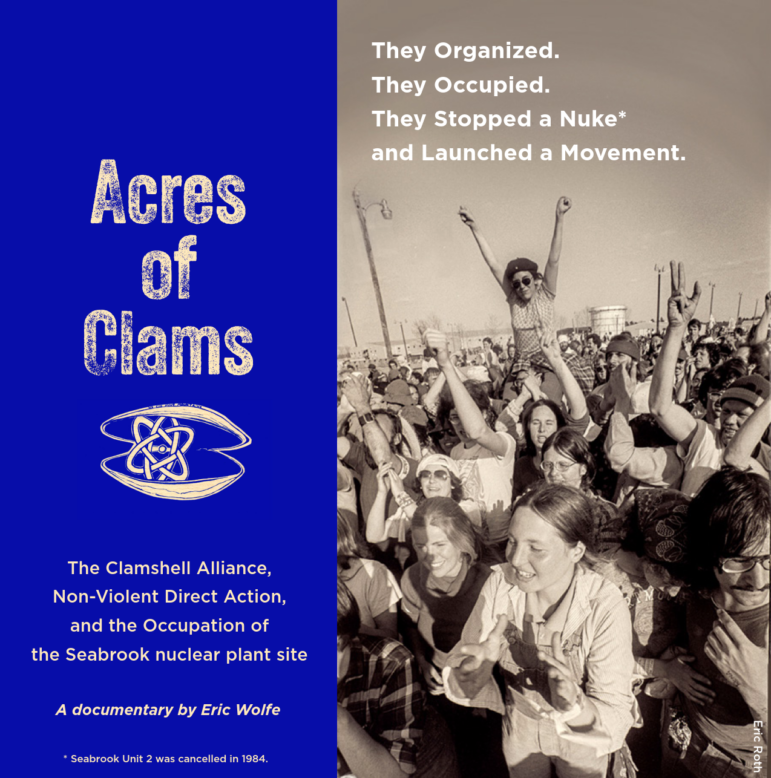

The group behind the protest was a ragtag New England-wide coalition that called itself the Clamshell Alliance, members of which called themselves “Clams.” How it was able to take on a governor and a powerful industry through nonviolent protest, music, and well-deployed humor is the story told in “Acres of Clams,” a new documentary written, produced and narrated by Eric Wolfe.

“You might find this story hard to believe. Hell, I was there, and I hardly believe it myself,” Wolfe says at the outset. He weaves his story from personal memories, archival photos and footage, and a series of oral history videos captured by Steve Thornton at Clamshell reunions held a few decades later.

Wolfe had arrived in New England from his native Kansas just in time for Clamshell’s creation in 1976, accompanied by a crew of hand puppets and a show he had created, “Burnt Toast: Trouble in the Nation’s Breadbasket.” The irreverent puppets, talking trash about nuclear technology, fit right in with the rebellious movement taking shape. Soon, Wolfe would be performing “Burnt Toast” from the back of a horse-drawn covered wagon making its way across southern New Hampshire to the first act of group civil disobedience at Seabrook.

That act would take place on the first day of August, when 18 people walked down a railroad track to the construction site, where they intended to plant saplings and native corn. The Seabrook police put them under arrest, facing a barrage of passionate, good-natured commentary on the dangers of nuclear power from the peaceful trespassers. Kristie Conrad, one of the 18 arrestees, would later point out that the anti-nuke protesters viewed the local cops not as adversaries but as neighbors, people with as much to lose from nuclear power as anyone else.

The Clams were deadly serious about the importance of stopping the spread of technology which would threaten to spew radiation across a heavily populated region. But Clamshell was also a good-natured movement, which Wolfe points out stood in marked contrast to angry anti-war protests in which he had participated just a few years earlier.

And it had a great foil in Governor Thomson. An ally of William Loeb, the arch-conservative publisher of the Manchester Union Leader, Thomson was the nuclear plant’s biggest cheerleader, and he did not want to be outwitted by a collection of mostly young protesters willing to go to jail for their beliefs and ready to parry every Thomson move with one of their own.

When the power plant suffered a regulatory hangup, Thomson put pro-nuke petitions in state liquor stores, where employees were ordered to promote them. When Clamshell members tried to place their own petitions alongside, they were sent to the parking lot, where they were arrested on Thomson’s orders. The Nashua Telegraph said Thomson had “played right into the hands of the Clamshell Alliance,” something he did over and over again.

As the date of the planned 1977 site occupation grew near, with one to two thousand people expected to join, Thomson would call the protest, “nothing but a cover for terrorist activity,” led by people who “do not plan to leave alive.”

But this was not a group of terrorists. All of them had been trained in nonviolence and agreed to what were called, “the guidelines,” in essence a code of discipline for participants, including no use of illegal drugs, no weapons, no running, no dogs, and no damage to the property at the construction site. Everyone knew they would probably get arrested.

What they didn’t know was that the governor would open up 4 armories as jails. What Thomson didn’t know was that the Clams would mostly refuse to pay bail until every last one of them was allowed out on their own recognizance. So, in the armories they stayed, each day getting more attention to their cause while they spent their time singing, swapping stories, and putting on workshops about nonviolence, the dangers of radiation, and the potential of solar energy.

With his own memories of 2 weeks in the Manchester Armory, and with stories collected on video years later, Wolfe captures the spirit of a movement made stronger through arrest and incarceration.

There are plenty of stories, many humorous, some poignant, and some which reveal the particular power wielded by people who use the tools of nonviolence. There was Ron Rieck, a pacifist apple picker who spent two frigid nights on a platform tacked onto a weather tower high above the construction site. He was arrested.

There was Paul Gunter, describing how a few people slipped into a back stairwell at the office of Public Service Company of NH, the nuke plant’s prime builder, hoping to have a chat with the company’s chief executive. They were arrested.

There was blind Nelia Sargent, using her cane to hold up a massive truck delivering the reactor pressure vessel to the Seabrook site.

There was Guy Chichester, who as the nuclear reactor neared operation, took a chainsaw to an evacuation siren pole. He was arrested, but later acquitted when he explained the Seabrook story to a jury of his peers.

And there was Charlie King, describing how he adapted an old folk song, “Acres of Clams,” to what would become the movement’s anthem.

There’s more to say, of course, and Wolfe wasn’t able to capture all of it. I missed mention of the Granite State Alliance’s campaign against “Construction Work in Progress” electric rates, which contributed to Thomson’s downfall. I would have enjoyed reliving the story of the “Armory Ball,” when Clamshell members rented the Portsmouth Armory for a party, only to have Thomson try to void the contract. But Wolfe had to stop somewhere to keep the film to a reasonable length, and he’s done a great job in his first time out as a documentarian.

“Acres of Clams” is not a documentary about nuclear power, still a controversial way to generate electricity, and one which the Clams I know still passionately oppose. If you’re interested in up-to-date information on why nukes aren’t the answer to climate catastrophe any more than they were the answer to oil imports in the 1970s, check out Beyond Nuclear, a group co-founded by Paul Gunter, who never stopped fighting nukes. And check out ClamshellAlliance.com, a relatively new website created to keep the group’s legacy alive and foster ongoing activism. What Wolfe set out to do, and succeeded, was to tell the story of a movement that flourished for several years and made history.

Wolfe’s film is not the first Clamshell documentary, but it’s the first to be produced since the 1970s, and it has the advantage of some historical distance from the times it chronicles. I’m hardly an objective viewer (you’ll see me several times in the course of the film), but I think Wolfe has done a great job showing that disciplined nonviolence, humor, cultural expression, smart political judgment, good timing, and a certain amount of luck could produce what might appear to be magic: a grassroots social movement that can take on and defeat a multi-billion-dollar industry backed by the state and federal governments. And that’s a story that’s not just about nuclear dangers.

“Acres of Clams” can be viewed, free of charge, on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RPuE9oKh6-I&t=198s.