Arnie Alpert spent decades as a community organizer/educator in NH movements for social justice and peace. Officially retired since 2020, he keeps his hands (and feet) in the activist world while writing about past and present social movements.

By Arnie Alpert, Active with the Activists

Amerika Garcia Grewal came to New Hampshire with a simple message: don’t let what happened in Texas happen to you.

What happened was Operation Lone Star, Gov. Greg Abbott’s plan to “defend” Texas from what he termed an “invasion” of immigrants crossing the border from Mexico. From Garcia Grewal’s vantage point, the would-be immigrants are largely desperate families who risk and too often lose their lives crossing the river separating the two countries.

Her vantage point is Eagle Pass, a small city on the Rio Grande, where she grew up and lives with her parents. When two bodies were recovered from the river in August of 2023, Garcia Grewal organized a prayer vigil in city-owned Shelby Park by the river. But the very next day, she said, “there were more bodies found in the river,” where Abbott had installed strings of buoys separated by saw blades. Eagle Pass residents held another prayer vigil in October, and every month since, on the first Monday of the month.

There’s been one major change: in January, the State seized Shelby Park from the City, surrounded it with a chain link fence, and told Eagle Pass residents that the park where families had held festivals and picnics, fished, and boated for years was off limits. The action “ripped the heart out of our community,” Garcia Grewal said. Instead, the park became the Operation Lone Star headquarters, a base for soldiers, helicopter landings, and military vehicles. Per Abbott’s orders, federal Border Patrol officers aren’t allowed there either. If Garcia Grewal jumps through hoops set up by the Texas Military Department, she can still get permission for people to pray in the park, but the presence of armed soldiers, fences, and barbed wire is enough to keep most people away.

The International Organization for Migration, a UN agency, calls the US-Mexico border “the deadliest land route for migrants worldwide,” with 686 recorded deaths in 2022.

Texas law requires the dead to be identified, but “due to the high volume of deaths and lack of county resources,” says Operation ID, a project led by specialists from the Forensic Anthropology Center at Texas State University.

According to the project’s website, “most counties were overwhelmed and began to bury the undocumented migrants, most without proper analyses or collection of DNA samples, without documenting the location of burial leaving little chance that these individuals will ever be returned to their families.

In turn, families are left without knowing what happened to their son, daughter, mother, father, brother or sister.”

Operation ID relies on volunteers, including Garcia Grewal, who displayed slides of the project’s work during a presentation in Pembroke last Saturday. It’s grisly work, taking fingerprints and DNA from partially decomposed corpses, some of which have been held at local morgues for months or years.

The deaths are just one of the harmful impacts of Operation Lone Star, which has cost Texas taxpayers $11 billion since Abbot launched it in 2021. In addition to thousands of buoys in the river, thousands of shipping containers lining the riverbank, and more than 90 miles of concertina wire, Texans have paid for several bases for the thousands of National Guard members and police officers staffing Lone Star, buses to ship immigrants to “blue” cities, prosecution of migrants for minor offenses like trespassing, and felony prosecutions mostly of US citizens for transporting unauthorized immigrants.

Lone Star has also equipped the Texas National Guard with pepper ball projectiles, which they have repeatedly fired at unarmed migrants attempting to cross the river. “In separate incidents this summer, witnesses saw Texas National Guard members firing pepper spray projectiles at migrants who posed no risk to National Guard members or anyone else,” said Bob Libal, Texas a consultant at Human Rights Watch, which issued a report in September. Amerika Garcia Grewal was one of the witnesses to the incidents.

“Under international human rights law,” Human Rights Watch said, “law enforcement may only use force—including less lethal weapons like pepper ball projectiles—when strictly necessary and proportionate to a legitimate aim. The UN Guidance on Less Lethal Weapons in Law Enforcement states chemical irritants should only be used where there is an ‘imminent risk of injury.’”

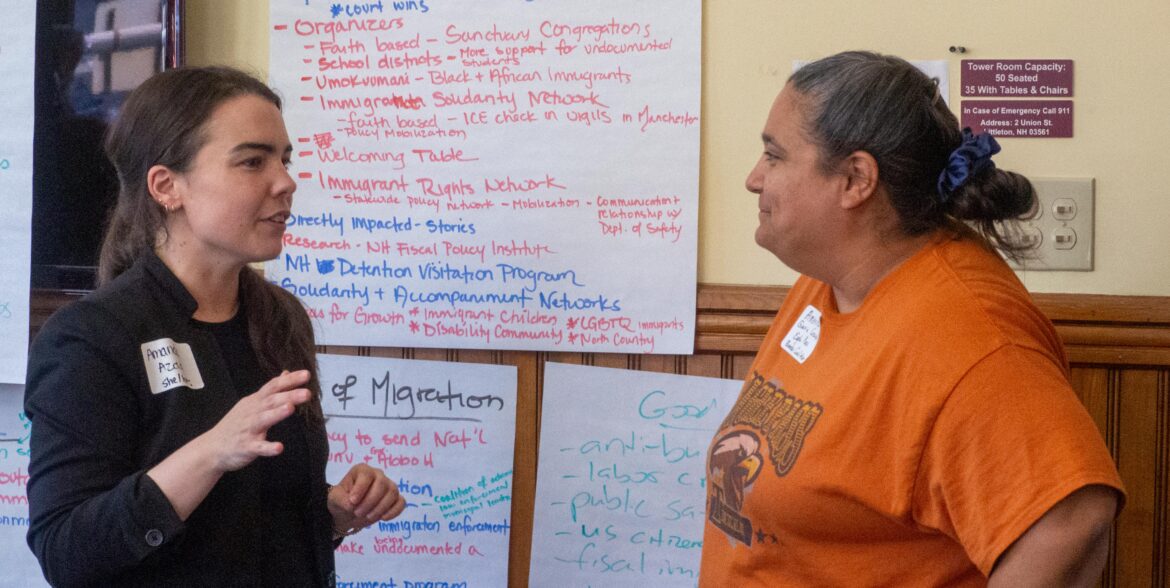

In addition, Garcia Grewal said, “Seventy percent of high-speed chases that happen in the state of Texas happen in border communities. We’ve had well over 100 deaths from those high-speed chases. We’ve had millions in property damage. We also have a very high rate of suicides with National Guard members who’ve been detached to the southern border, but also with Customs and Border Patrol,” she told a group of immigrants’ rights activists at a strategy meeting in Littleton.

Operation Lone Star has also disrupted the local economy, which for generations has depended on cultural and commercial ties with Piedras Negras, Eagle Pass’s sister city across the border. For an impoverished community–Maverick County, where Eagle Pass is the biggest city, ranks 250th out of the state’s 254 counties when it comes to per capita income–militarization has come at a high cost beyond the state budget impact. “The closer you looked, the more there was to look at,” Garcia Grewal said.

“The funds spent on Lone Star is money that would have been education. This is the money that would have been healthcare. This would have been our roads,” she said.

Last week, Gov. Abbott asked the Texas legislature for another $2.9 billion for “border security.”

Gov. Chris Sununu

Something similar could be said about New Hampshire, where Gov. Chris Sununu allocated $1.4 million for his Northern Border Force, a mini-Lone Star responding to a trumped-up (pun intended) crisis along the state’s 58-mile border with Canada. He sent a unit of the National Guard to Texas for a year in 2022 to work alongside the Border Patrol. He joined Gov. Abbott and other Republican governors in a Shelby Park publicity event last February, and in April he sent another unit to Eagle Pass to join Operation Lone Star. In several statements, the governor said the exercise was needed to stop drug trafficking, even though analysts believe most illegal drugs enter the United States carried by U.S. citizens crossing at ports of entry, not migrants wading across the Rio Grande.

The latest National Guard mission cost New Hampshire taxpayer $850,000.

If we’re so concerned about fentanyl, said Eva Castillo of the NH Alliance for Immigrants and Refugees after Garcia Grewal’s talk in Pembroke, “we should invest more in preventing people from using drugs” rather than using force and violence against immigrants desperate for safer lives in the United States.

Castillo, New Hampshire’s most experienced and indefatigable immigrants’ rights advocate, said she sees the northern border and National Guard missions as “planting the seeds” of something like what is going on in Texas. It’s a sign of upside-down priorities, spending money on soldiers and policing “instead of using them on the people and their needs.”

More Texas-inspired policy may be on the horizon, modeled on a bill Abbott signed last December which authorizes law enforcement officers to arrest and deport people they believe to be unauthorized immigrants. The law is being held up in federal court, but it has inspired copycat bills, including one expected to come to the New Hampshire State House next year. Rep. Joe Sweeney says he wants to make it a felony for unauthorized immigrants to be in New Hampshire at all and to create a state deportation task force. (For State House watchers, it’s LSR 0012 for the coming session.)

The Sweeney bill, the northern border, and the political hostility to immigrants which is so evident in election season politics were topics of discussion for the meeting in Littleton last week where representatives from the ACLU, NH Legal Assistance, the American Friends Service Committee, NH Council of Churches, Granite State Organizing Project, Welcoming NH, and others heard Amerika Garcia Grewal’s warning loud and clear.

Together, the group has beaten back a host of anti-immigrant bills over the years and almost succeeded in stripping the Northern Border Force out of the 2023 state budget. They’ve already got their eyes on Sweeney’s proposal and are gearing up for another budget debate.

At the Pembroke meeting, Garcia Grewal said “doing things here in New Hampshire will help me in Eagle Pass.” The “doing things” agenda they discussed started with Castillo talking about the importance of resisting efforts to dehumanize immigrants. Others spoke about sifting through deceitful political messaging about drugs and human trafficking. “They have to resort to lies because the truth isn’t scary enough,” suggested Chris Wellington, whose background includes policing and immigration law.

Martin Toe of the Granite State Organizing Project described a campaign called “Invest in Us,” which he said looks at “how we can redirect our tax dollars towards local issues and public services” instead of devoting funds to projects like the Northern Border Force and Operation Lone Star. He said he found receptive people on the streets of Littleton, where he used his smart phone to record short videos asking people how they want their tax dollars used.

Garcia Grewal concluded the Pembroke meeting by asking everyone to take out their calendars and say what they are going to do and when they are going to do it. Among the responses were education of church congregations, research on anti-immigrant legislation, writing to members of Congress, and wearing buttons that say, “I’m pro-immigrant and I vote.” I said I’d write a column for InDepthNH.org.