This article was first published in Connecting

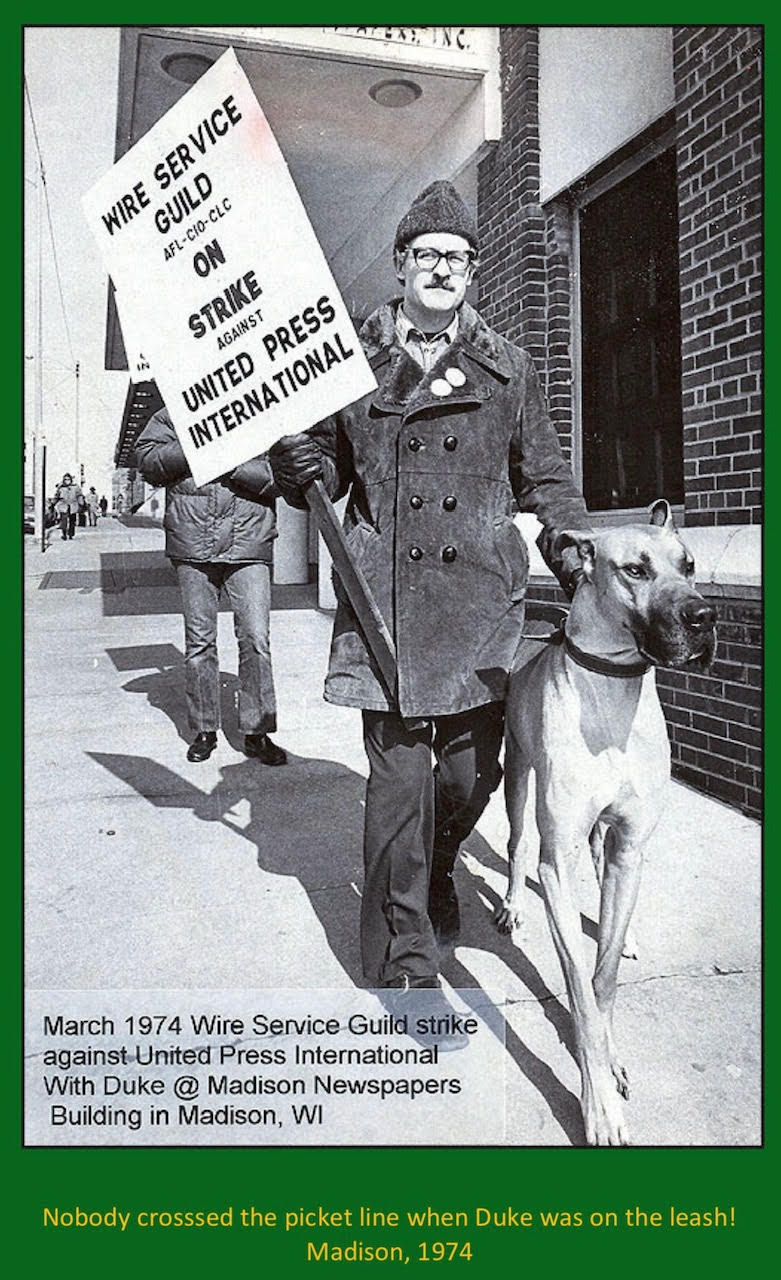

Adolphe Bernotas – Fifty years ago this week, United Press International staffers represented by Local 222 of The Newspaper Guild were in the midst of their strike against Scripps-Howard company. It was the second strike called by the Wire Service Guild and lasted 23 days. The first strike by the local was against the Associated Press five years earlier, lasting eight days. In many bureaus around the United States veterans of the AP strike and AP staffers joined their UPI brothers and sisters on picket lines.

What follows is the story of the UPI strike, told by one of its top leaders, Mike Kaeser, WSG president at the time. Mike and I spent many years as comrades-in-arms in WSG leadership.

Mike started in the Madison bureau in 1963, then Milwaukee, Lincoln, Detroit and Chicago. He left UPI in 1978, rejoined in 1982 for a stint in Dallas, San Francisco and Chicago, leaving UPI in 1985. Before he retired from the Santa Rosa Press Democrat, Mike had worked at the Florida Times-Union, Braniff and Midway airlines, and at the Los Angeles Times for the Times-

Here is Mike Kaeser’s account of the strike:

In 1974, we called for a strike-authorization vote as soon as management submitted its money offer, not unheard of timing. Such votes usually pass by wide margins, but sometimes the members privately tell the negotiators “we’ve handed you the loaded gun, but don’t pull the trigger,” which makes the poker game of negotiations more tricky. This time, we had tremendous backing. After a major organizing drive, we had the highest percentage of membership in WSG history.

The one exception was the computer department in New York, which Chuck Wallace from the foreign desk focused on but could not crack. This raised the suspicions of Edna Berger, the TNG rep assigned to our negotiations, who had us ask for the months of overtime records we could get under the contract. An interesting pattern was uncovered: The lead programmer was working 80 hours a week, for months, meaning he was making 2.5 times the contract scale. The No. 2 programmer was working about 75 hours, and so on down the line. They were probably being paid the industry going rate for tech people, but UPI, being cheap, didn’t want to give them permanent raises above scale, so this under-the-table scheme was used to keep vital employees keeping the computer running. I don’t remember how UPI dealt with the problem.

The strike lasted 23 days. Every morning we woke up worrying whether the troops were still on the picket lines or whether the whole thing had collapsed. But our folks held strong. What they were going through made our part look easy.

Harry Culver (TNG chairperson at the time), who’d come in to do payroll analysis as only he could to cost out various pay offers, basically ran the WSG office and communicated with members around the country while the bargaining committee of Drew Von Bergen, Bruno Raniello, Karl Kramer and me was occupied at negotiations. Chris Graham from the UPI radio network provided a professional voice for the daily messages on the answering machine that updated members — and management who also checked them. The negotiators, basically living in New York for more than two months, made a couple of trips home to meet with our members. When we were in an information blackout imposed by a federal mediator, Von Bergen went back to DC and was confronted by the legendary White House correspondent Helen Thomas, who demanded to know what was going on. When he balked, she told him, “Lyndon Johnson couldn’t keep what was going on in Vietnam from me, and you’re not going to keep this from me.” One suspects there followed what is known in Washington circles as a conversation on “deep background.”

The night the strike ended, our guardian angel Edna Berger took our committee for drinks at her apartment where her husband, Gerald Marks, serenaded us with some of the Tin Pan Alley songs he’d composed. Harry, who did not drink, had one small sherry.

When the strike ended at midnight, the pickets in Chicago went upstairs and greeted returning employees with standing ovations. I took a couple more unpaid weeks to run out my three-months of allowed Guild leave, decompress and likely keep myself from putting my fist through a computer screen if I’d gone back right away. When I finally went in, the place erupted in applause, an honor that made me proud to have served them.

The strike may have ended but the battle soon resumed. All of our money proposals called for reducing the step-ups for the Newspersons, Photographers classification from six years to five. Amazingly, it seemed, all of UPI’s offers did exactly the same thing. This was a very BFD. However, when UPI put all the pieces of the contract together into the final typed version for signing, there suddenly were two scales for that classification: a six-year one for current employees and a five-year one for new hires. That had never been put on paper by the company during negotiations, so we started litigating, which was still going on when the 1976 talks began.

UPI had been outraged and embarrassed that their major star Helen Thomas had gone out on strike. Covering the White House was so important, the magic wand was waved over Helen, who was declared manager of a separate three-person White House bureau, which made her exempt from Guild coverage. UPI had a history of sprinkling managerial titles like fairy dust, and the Guild took the issue to arbitration, which was still pending in 1976.

UPI also quietly docked all the strikers 23 days of seniority for their time on the picket line. We were off to the National Labor Relations Board with an unfair labor practice complaint.

After the strike, there was some grumbling from the ranks that we hadn’t gained much over what was on the table when it began. One thing we did gain was our self-respect as a union and the respect (or fear) of management, which fell all over itself two years later to avoid a repeat and make us happy. I may be imagining this after all these years, but I believe I opened the 1976 negotiations with the words, “As we were saying…”

We went back in 1976 with the same TNG model contract all locals must submit before amending it to more practical terms. This time management was not as openly hostile and we did our part by quickly jettisoning the parts that didn’t apply well to a wire service. UPI’s chief spokesman again was Scripps-Howard labor lawyer Jack Novotny, a former Marine given to such verbosity, orally and in the writing of flabby contract language, that I was convinced he was being paid not by hour but by the word. He was quickly nicknamed Monotony. Trees died as we endlessly passed paper back and forth, Jack padding every paragraph, the editors on our side doing heavy editing and shoving it back.

Trying not to trigger another instant strike authorization vote, Novotny kept assuring us that the eventual company salary proposal would be “a ballpark offer,” not a take-it-or-leave it one as in 1974 when UPI made it clear it would not exceed levels in the recent AP contract. By the time Novotny finally said the “ballpark” money would arrive in the next session, we were ready. Company negotiators walked in to find Walter Wisniewski, Mike Conlon, Jim Pecora and me wearing yellow and blue rugby shirts. “OK, Jack, we here to play ball,” I said. We called them the bumblebee shirts, after a running SNL skit and wore them only when talking money.

Nothing signaled the difference in UPI’s willingness to listen and bargain between 1974 and 1976 than a session involving the lowest-paid classification, the mail room aides. Some of the young men came in to make a pitch for a little something extra — a slightly higher percentage raise than other classifications might get because they were paid so pitifully little. Management brought in the mailroom foreman, George Muldowney, a former Guild officer before the management wand got waved over him. Moldy, as his staff called him, did not look comfortable on that side of the table. Monotony delivered the most condescending speech I’d heard in two negotiations, saying that UPI had only so many resources to spread around and had to put them where they would do the most good, with the editorial staff, and besides you can never grow up to be president.

The young lad next to me shot back: “Al Bock started in the mailroom.” Bock was the company controller, the guy who signed the checks. Novotny was stunned. He mumbled something polite and indicated they’d see what they could do. In the end, the mailroom aides did get an extra boost.

You may have heard of that bright kid. His name is Kevin Keane and he went on to become Guild administrator.

In 1974, when we were embarrassing management with a cache of company documents and they wanted to know how we got them, Edna had said, “The Angel of Mercy left them on our doorstep at the Guild office.” In 1976, the new general manager reached out to me before the talks to say that if we ever felt that our message was not getting past their negotiators (translation: Novotny) to higher management we should contact him directly. After another day of endless, unproductive haggling over a relatively minor issue involving the horse racing wire, I ended the nightly phone message cryptically: “On this issue, the Angel of Mercy has yet to hear from the Horse’s Mouth.” An hour later someone in management tracked us down and gave me a number to call. It’s was the GM’s home number. His wife answered, asked who was calling, and I said, “Tell him it’s the Angel of Mercy.” The result was a private rendezvous with him the next day at the Waldorf coffee shop where Wisniewski and I cleared the air on a number of issues, setting the stage for a contract deal a couple of nights later that finally resolved all three matters of dispute outstanding from 1974. The dual scale disappeared with the five-year plan prevailing; the 23 days seniority days were returned; and Helen would continue to be exempt until she left, whereupon the imaginary bureau disappear back into the DC bureau.

As a parting gift, we gave Novotny a book on how to write clear contract language. The inscription “From the Angel of Mercy” was typed, somehow, so as not to give him any clue who the original angel might or might not have been. Like Bob Woodward, I will not reveal my sources.

Over the years, I had edited any number of labor stories that used the phrase “hammered out an agreement.” I considered it a cliche and would change it to “reach an agreement.” One word shorter and less trite.

My opinion changed after my experience at the bargaining table. It really is incredibly hard, stressful work.