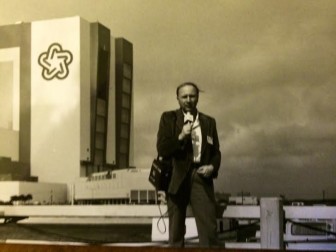

Roger Wood is pictured in Cape Canaveral, Fla. the day of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster on Jan. 28, 1986.

Roger Wood

On Jan. 27, 1986, I sat in a motel room in Florida watching the New England Patriots get trounced 45 to 3 by the Chicago Bears in their first Superbowl Appearance. After the lopsided loss, I said to the other reporters, “At least tomorrow will be a great day for New England.” I was referring to the history-making flight of Concord High School teacher Christa McAuliffe, who had been chosen from a nationwide pool to be the first teacher in space aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger. Months before, I interviewed Christa during a celebration parade in her home town. Jan. 28, 1986, was to be a joyous day for her family and the state of New Hampshire.

InDepthNH.org is reprinting Roger Wood’s journal about covering the tragic events of Jan. 28, 1986.

By Roger Wood, InDepthNH.org

Florida’s Kennedy Space Center is an hour and a quarter drive from Orlando and was to be my temporary home for the week. The spaceport at Cape Canaveral is huge and spread out, with miles of flat roadbed surrounded by swamps and wildlife areas separating the outermost gate and the space shuttle launch pad.

My associate Jim Van Dongen and I were to make that trek over flat, palm tree-dotted marshes and woodland four times during these five days in the hope of seeing a New Hampshire neighbor turned celebrity make a long-awaited journey into space.

Jim and I landed at Orlando International Airport around 3 p.m. on Thursday, Jan. 24, 1986, our Eastern Airlines flight delayed about half an hour at Logan International Airport in Boston because of a last-minute mechanical adjustment to the plane. We were both assigned by our radio stations to cover the historic event and decided to go together and share some of the costs. I am employed by 50,000 watt WOKQ FM in Dover, and Jim for WEVO, New Hampshire Public Radio in Concord. We have worked together many times.

The two stations have traded news stories for years, shared news staffs for elections and other events, and saw this opportunity as a culmination of our efforts to provide listeners back in New England with important on-location news coverage.

Landing in Orlando, we proceeded directly to the media telephones at the airport after briefly interviewing Concord Superintendent of Schools Mark Beauvais who was on our flight. Beauvais was Christa McAuliffe’s boss before her selection as NASA’s first teacher in space, and he too, along with a large delegation of New Hampshire educators, was sent to Florida to witness the flight. Beauvais was exuberant upon landing in the warm climate after leaving frigid New England.

I sent a report by telephone with a clip of the interview and a promotional announcement promising continuing coverage until the big day, now scheduled for Saturday, but threatened with another delay because of an approaching weather front.

The next morning, Friday, found Jim and I at the hotel restaurant eating a buffet of scrambled eggs and sausage before making the Cape ride. With our electronic gear packed in the rented Mustang’s trunk, we headed back up the Bee Line expressway through its frequent toll plazas and for a time it seemed out of civilization.

The busy, crowded avenues of Orlando filled with rental cars taking tourists back and forth to Disney World were replaced with the empty, open expanses of swamps and palm trees as we drove along the expressway to the coast where we knew our work awaited us in an unfamiliar setting.

New England radio reporters seldom go so far for a news story and it took me weeks to convince my station’s management that it was worth spending the money on the project. Ultimately, it was my assurance that this would be a history-making flight that won the assignment. But that Friday morning as we crossed over the Atlantic Intercoastal Waterway, I had no idea how much history I was to witness.

There was no guard posted at the Kennedy Space Center’s outermost gate, but at Gate two, tourists were instructed to turn off the roadway into a designated area while we proceed on to the news media badging center.

There, reporters were picking up their credentials, among them veteran radio correspondent Jay Barbree of NBC, a witness to every manned space flight ever launched from Cape Canaveral. Tanned and casually dressed, Jay seemed to know everyone at the spaceport and graciously showed us how to get around the huge facility.

Inside the domed media center, I got a quick lesson on protocol and located my desk space along the circular rows. My space next to Jim’s contained our telephone jack, another shared cost for both stations, and an electrical outlet. We sought out a NASA spokesperson for a shuttle update, found out it had been officially postponed until Sunday and settled in for a day of orientation.

All the major networks and news services have their own permanent buildings or trailers on site. Jim and I wandered over to the United Press International trailer and did a feature interview with Rob Navias, their K.S.C. reporter. One of their journalists turned around and quizzed us about the New Englanders along on the trip for a possible news feature.

Not only were there several radio, T.V. and newspaper correspondents from New Hampshire, many of the Boston and Portland stations were represented as well as a radio team from Framingham, Mass., where Grace and Ed Corrigan, Christa’s parents live.

Not much was happening that day at K.S.C., so I took my camera out and posed for some publicity-type shots around the media center, Vehicle Assembly Building and count-down clock. I then turned around and photographed Jim in the same places. My manager had suggested the photos could be used in future ad campaigns for the radio station, or at least hung up in the hallway at WOKQ. Lunch was cafeteria style, eating with other employees of the space agency in a nearby building.

We left Kennedy that afternoon knowing there would be no launch the next day, but hopeful that it would take place on Sunday. Our travel plans, made through a charter, called for leaving on Monday and postponements already had caused some of the New Hampshire people to leave early. Nevertheless, we again trekked over on Saturday, sending more feature interviews and reports back to New England, mainly with New Hampshire residents who were there.

One of them, Robert Veilleux, was the Manchester teacher picked as a semifinalist for the teacher-in-space program. I interviewed him at his Orlando hotel room before he took a close-up tour of the space center and the Shuttle Challenger. Veilleux conceded that he wished he was going aboard the shuttle, but added that the choice of a teacher to be the first citizen in space would be a boon to educators everywhere.

Later that day, we were advised by NASA that a threatening weather front could pass over Florida at a critical time for a Sunday launch and that another delay was possible. Before leaving the center that day, spokesman Dick Young told us that a management meeting would decide it and that the answer would be available by telephone that night.

On Sunday, there was no point in going to the Cape, since we learned that there would indeed be another delay because of the prediction of bad weather. In actuality, conditions at launch time were excellent Sunday morning, but the blast-off was rescheduled until Monday at 9:37 a.m. Jim and I mainly rested that day, taking a ride to nearby Lake Buena Vista to Disney World Village to do some shopping for our families back home and have lunch at the Empress Lilly.

It would be an early night for me with a 3:30 a.m. alarm set for the ride back to the coast.

It turned out that the alarm clock wasn’t necessary with the excitement and uncertainty inhibiting sleep early Monday morning, January 27. As if on cue, both Jim and I vaulted out of our beds. We left the motel room for a quick breakfast before dawn at a Denny’s on International Drive. Believing that the shuttle would be launched on that morning, I wanted to be at the Kennedy Space Center before 6 a.m. to send back a preview report in time for the first newscast of the day.

Approaching the Cape, the Challenger looked like a huge monument on the flat Florida landscape illuminated by two brilliant floodlights. Though miles away, the craft, sitting on its launch pad that pre-dawn morning was in impressive sight with a look of permanence as if it were meant to be admired as a work of art, not a conveyance to space.

Just days before, we drove right through the outermost security gate on the K.S.C. compound, but on this morning, there was a guard posted, more evidence that something was going to happen this time. I noticed many campers and other recreational vehicles lining up alongside the highway, their drivers vying for the best position to see the launch, now set for 9:37 that morning.

It was still dark when I pulled into the media center parking lot just after 5:30 a.m. The countdown clock was running and NASA’s Dick Young, one of the many public relations spokesmen charged with keeping us updated, was still talking about the weather being a factor. This time it was the possibility that high surface winds could hinder the launch if it were delayed too long into the window allotted for that day.

We didn’t want another delay. As reporters assigned to cover the New Hampshire angle to this flight, we were beginning to run out of ideas. New Hampshire Gov. John Sununu, scheduled to view it over the weekend, definitely wasn’t coming and many of the school officials who had come to Florida to participate were on charter trips and had to return early.

Our flight home to New England was scheduled Monday night as part of the terms with Crimson Travel, which arranged our trips with economy in mind. Some New England journalists were talking of leaving as well if another postponement pushed the launch back towards the end of the week.

On NASA T.V., we began to see pictures of the astronauts awakened early and getting ready for a blast-off. We watched the crew at breakfast, then leaving their quarters, entering the van, riding to the launch pad, and finally entering the “White Room” to finish suiting up for entry into the Challenger. Although there were clouds in the sky, Hugh Harris on the launch control speakers was talking about a “hole” of blue sky, which should arrive at around the right moment for a clear shot.

Feeling that there would finally be a launch to report, I started bringing my electronic equipment out to the press grandstand for a live broadcast back to both WOKQ and WEVO. Through an agreement with both stations, we would send our coverage back to WOKQ and WEVO would pick up our air signal live and re-broadcast it. Jim and I would co-anchor that live broadcast, then get some quick post-launch reaction from spectators, pack the car, and head back to Orlando for the flight home.

That plan turned out to be short-lived, however, as the delay jinx continued. Excitement turned just as quickly to anxiety, and then disappointment, as we watched launch crews wrestle with the bolt on a balky hatch door, which had to be secured before launch. The countdown clock had ticked down to just minutes when this latest glitch took place, and it was soon clear that there would be no quick fix to the problem.

Further threatening the launch was the weather, clear for a time, but now clouding up and getting windier. Just as the crews were cleaning up inside the white room, we got the word that cross-winds presented a “no-go” for launch unless they improved. By now, those winds were whipping across the ground, rustling through the palm trees, blowing through the grandstand, and finally, scrubbing the launch for Monday.

We had already checked out of the motel, but I called the desk and reserved a room for the next two nights. Tuesday morning, Jan. 28th was crystal clear, but icy cold — typical weather for a New England mid-winter early morning, but unusual and unwelcome for the citrus belt.

Frost warnings had already been posted the night before for orange growers and the temperature was far below freezing that morning. We had already been warned at Kennedy that sub-freezing temperatures could very well force another cancellation of the shuttle launch, so neither Jim nor I expected any activity when we drove to the Cape that morning.

In fact, my radio reports the previous afternoon suggested that it would be unlikely for a launch until better, warmer weather arrived was therefore amazed when, upon reaching K.S.C. I heard the public affairs officers saying that it looked like a go for that morning.

At 24 degrees Fahrenheit, it was bitterly cold at the Cape, a piercing kind of cold that can only be compared to a below zero, wind-chilled New England day.

I was uncomfortable in a lined raincoat and warm gloves, but many of my counterparts from the North were equipped only with light spring jackets or sweatshirts, expecting the balmy weather that Florida is so well-known for. I asked NASA’s Dick Young if a space shuttle had ever been launched in such temperatures, and he conceded there hadn’t, but he downplayed my line of questioning saying that the agency had launched other types of rockets in weather that cold.

I also took my question to Col. Robert Nicholson, an Air Force weather expert on hand at the media center. He told me that rising temperatures after sunrise should help improve conditions and that the ice control team seemed to have kept ahead of that problem on the launch pad. But the residue of that team’s overnight work was still to be seen on the underside of the launch platform.

There were long icicles clinging to the surface just as they do to the roof eaves of our New England homes. It was those icicles that forced the last postponement, this one to 11:30 that morning for the Challenger liftoff.

When the sun finally rose the morning of the 28th, it had a warming quality to it and there was absolutely no wind. Since there were no clouds in the sky, the cold and icing on the launch pad were the only remaining obstacles.

I and my fellow New England reporters were ecstatic, sensing that this would probably be the day we would witness a shuttle launch and record the historic beginning of a journey for space-teacher Christa McAuliffe.

Some of us had almost run out of cash and clean clothes, and certainly all of us had exhausted our news feature interview possibilities. The only thing left to report on was the launch itself.

After the last hold was called to evaluate the icing situation, a problem presented as minimal to us by NASA, we prepared to lug our radio equipment back out to the grandstand, which was still freezing after only a short time in the sun. On the NASA T.V. screens, after watching the astronauts go through their routine, just a picture of the icicles remained.

Then, word from launch control that engineers determined they would be gone by the time of launch, now set for 11:37 a.m. I phoned my station and briefed them to expect a live lift-off broadcast beginning just after 11:30 and continuing only until a short time after the blast-off took place. I began to feel, like many of my colleagues, that the story was near an end and that my trip back home was imminent.

I can’t really remember when I began to believe that something was wrong. I had just finished a short, live radio broadcast on the lift-off of Challenger, when a voice from mission control in a very low-key voice crackled something about the vehicle exploding.

Then, more silence on a system that had been alive with sound beforehand. Then there was a report about search and recovery operations beginning off the coast, but no official announcement from NASA. That was to come, fully five hours later at a news conference by Jesse Moore that added very little information.

What was a New England radio reporter who had never seen a rocket launch in person to do? I was sent to the Kennedy Space Center to report on the triumphant journey of New Hampshire teacher Christa McAuliffe, not the horrible deaths of seven human beings in an incredible explosion that reverberated throughout the press grandstand and in the living rooms of Americans watching in horror.

When the awful truth began to filter back from the V.I.P. grandstand nearby that the worst had happened, the initial roar of the shuttle rocket engines had already passed and was replaced with an eerie quiet. Up in the sky there were trails of vapor and smoke going in all different directions, but no sign of the Challenger.

I packed my electronic equipment and moved from the chilly grandstand into the domed media center. There, reporters who were usually busy writing a feature story about the mission or crew or socializing, were just standing or milling around.

Some were wiping their eyes, most appearing to be in shock. Others were crowded around pay phones trying to send back the almost non-existent information that was available. My manager back in New Hampshire wanted updates on the disaster and I was still in disbelief.

By then, realizing that there was no official information forthcoming from NASA, national and local T.V. crews were roaming the morgue-like media center trying to find something, anything to capture on film or video. As soon as I began writing or picking up our special phone link back to New England, a still or video camera person would focus on me.

Totally numb at first, I began to try and think of a story to tell. Just then, 16-year-old Brian Ballard, who accompanied another New Hampshire radio reporter to the Cape, walked through and I remembered that he was the editor of Concord High School’s newspaper. Just a couple of days before, he had sat around with a group of us watching the Super Bowl game.

Now, I recognized him to be the only source of immediate local reaction so I beckoned him over to my press desk. Immediately, the rest of the New Hampshire press corps joined me and in minutes, the youth was lost in a sea of microphones and video cameras, an instant celebrity in an incredibly upside-down world.

The interviews were still going strong, network reporters were asking him to come to their buildings when I phoned the story and his eyewitness comments into WOKQ. Jim Van Dongen of WEVO then used our joint telephone to call in a report to his station and National Public Radio.

I vacillated from complete involvement in writing and producing news material to sitting quietly at the desk wondering what was really happening. Up since 3:30 in the morning, I wasn’t hungry, but an empty feeling reminded me that I hadn’t eaten since breakfast.

One of my fellow New Hampshire radio reporters was having a difficult time dealing personally with the tragedy and at one point said he didn’t know how he could go on. Minutes later, he was again at his desk sending reports back to worried listeners in Concord.

Later, Jim Cole, also from Concord, an Associated Press photographer assigned to shoot pictures of Christa McAuliffe’s family and others in the V.I.P. grandstand at K.S.C. dropped by my desk, and I interviewed him.

Jim, who wasn’t even looking up into the sky at the doomed shuttle, was taking pictures as Christa’s family as they watched the horrible scene unfold. His observations also found their way onto Public Radio networks and others around the nation.

By now, there was still no official word from NASA, just a video scene of the apparent search area off the Atlantic Ocean. The action meanwhile had shifted, temporarily elsewhere, to Concord, where we heard that students were excused from an assembly called to watch the historic launch and that school officials would speak to the media there at 3 in the afternoon.

Here, finally an advisory came on the NASA T.V. screens that the agency’s Associate Administrator of Space Flight, Jesse Moore would have a statement in the auditorium next door at 3. However, the news conference kept being pushed back, fifteen minutes at a time, until finally at 4:30, he released few details with the awful confirmation that the shuttle exploded killing all seven astronauts.

We also watched President Reagan from Washington attempting to lift the spirits of shell-shocked NASA employees, along with children and other Americans everywhere. Next on the video screens, a picture of the flag, outside by the grandstand at half-mast right next to the countdown clock, which was still moving into plus hours, minutes and seconds, but no longer recording a mission into space.

Just three days before, I had my picture taken in front of that clock, with the flag flying high and proud and the still intact space shuttle sitting on its pad.

The pictures I had taken for the radio station’s possible publicity use will probably simply be placed aside, along with my press badge, car window press sign and the next morning’s local papers with their shocking headlines.

I can’t even imagine wearing my NASA souvenir one-size fits all cap, and I neglected to buy any space souvenir toys to bring back to my children.

Life at the Kennedy Space Center by late afternoon was dreary with most of the information and reaction now coming from New England and other parts of the nation. Another advisory flashed on the video monitors, that Vice President Bush would be in the auditorium, along with space pioneer John Glenn and Utah Senator Jake Garn, the first non-astronaut to fly in the shuttle.

We had expected Bush on Sunday to view the launch, but when that date was scrubbed, he wasn’t able to be in the V.I.P. stands on the fateful morning.

After a 5:30 p.m. radio update, exhausted from the early morning rise and a devastating day, I was ready to pack it in.

Besides, this story belonged to the national media now, and it seemed like an appropriate time to leave the base. In the heavily secured K.S.C., we drove out of the press parking lot with no delays and left. Incoming lanes to K.S.C. were blocked by security vehicles.

The next morning, Jim and I secured a Delta flight to Boston leaving in the early afternoon. On it were other reporters from New England, from Channel 9 in Manchester, Channel 13 in Portland, and the Concord Monitor. Some were talking about the logistics of covering such a story, while others were quiet and pensive on the trip back.

As I write this, I am not sure whether or not I’m grateful to have been dealt in on the biggest news story since the John F. Kennedy assassination.