By PAULA TRACY, InDepthNH.org

MANCHESTER – Samantha Plantin, the daughter of slaves, who may be the first African American woman to own property in the City of Manchester, is about to get the recognition she is due.

Her philanthropy to help the education of African Americans and establish funds at two notable colleges is part of an effort by a white man with Irish roots who is working to uncover the black history and display it in his native Queen City.

Upon her death, Plantin gave the proceeds of those land purchases, which were sold to her by the Amoskeag Manufacturing Co., to Tuskegee University and at the now-defunct Haines Institute in Augusta, Georgia, for the purpose of Black education.

The woman along with other African Americans and white people who made a lasting contribution are expected to be among the first markers as part of an effort to create a history trail in Manchester.

Stan Garrity, an amateur historian said Plantin came from New Boston and worked in the mill first as a washerwoman and then as a dressmaker.

“She saved all her money,” Garrity said and was able to buy two parcels of land from the Amoskeag Manufacturing Co. on Concord Street.

He said she is likely one of the first Black people to own property in the city. Her last will and testament left those assets to be sold and the funds to be used to support black education, paying it forward for many countless individuals.

JerriAnne Boggis, executive director of the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire, which is based in Portsmouth, said there is a lot of black history in Manchester.

“We are encouraged to know that more people are taking an interest in New Hampshire’s Black history. The BHTNH has been documenting the role of the earliest European settlers in the capture and transportation of African children and adults who would be sold into slavery in the Americas.

“Since 1995 we have established historical makers in Portsmouth, Milford, Warner, (and) Hanover…to recognize the African American presence in New Hampshire history. In addition to guided history tours, the BHTNH offers public education events and programs, such as the current series of Tea Talks that discuss a wide range of anti-racist topics. For instance, we point out that words matter by pointing to inaccurate language such as ‘born a slave’ to describe a baby whose mother was being held in slavery by the highest bidder.”

Garrity said Manchester had many abolitionists, white people who sought to bring freedom to slaves.

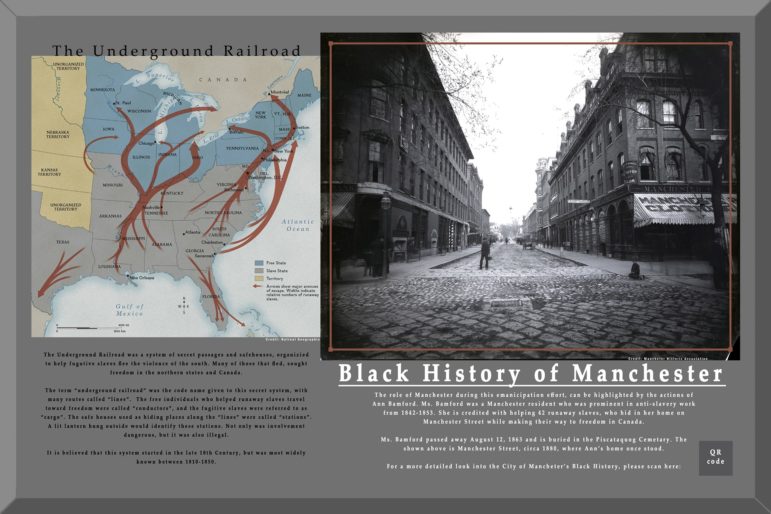

The first historic marker he has been able to create honors Ann Bamford, a white Manchester woman who between 1842 and 1858 harbored and successfully helped 42 slaves to freedom in Canada.

The first marker was placed at the corner of Elm and Manchester streets in the center of the city just in time for February, which is Black History month across the nation.

It tells about the Underground Railroad on one panel and Bamford’s contribution on the other.

An immigrant from Ireland, Bamford was a widow who lived at two homes on Merrimack and Manchester Streets.

In her later years, Garrity said she lived with her daughter and her son-in-law until her death in 1863.

“It’s kind of hard to prove because there were no records,” he said, noting the Underground Railroad was a series of secret homes connected from the south to the north in the 1800s before abolition to ferry slaves to freedom. It was unlawful to harbor escaping slaves and there were many bounty hunters looking for such slaves to return to their masters for a price, he noted.

It was in 1857, before the Emancipation Proclamation, that New Hampshire abolished slavery and made it a crime punishable with a jail sentence to own slaves, following similar action in Massachusetts, Garrity said.

Using city vital records, old newspaper articles, scanning graveyards, and collecting information at the state archives, Garrity, a member of the mayoral-appointed Manchester Heritage Commission, uncovered records.

He said he wants to highlight the work of Bamford and others who made a lasting impact as citizens of the city but who have remained largely unknown for the last 160 years.

He said he came across an Oct. 28, 1902 article in the Manchester Mirror and American about Bamford and got encouragement and help in some of his research from John Jordan, whom he described as “a good historian,” and made a number of other discoveries which he hopes to add as a walking tour of markers set up across the city.

Garrity said his family came from Ireland to work in the city. Immigrants, he said, built the city to what it is today and continue to come “just from other places,” not so much just Europe, and still provide a vital role to the city’s culture and life experience.

He retired as a captain of the Manchester Fire Department in 1984 and said he has been committed to helping other residents understand their history.

His goal, he said, is for other residents and visitors to appreciate the fact that the city has been a home to so many and their contribution to its rich history which is largely unknown.

He admits he has had a bit of pushback from some people in Manchester who do not think it worthy.

“But there is going to be a sign about these things,” and he said he is determined to bring their stories to light.

He said he has created a Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/Black-History-of-Manchester-228786582442026, and hopes to get people to contribute information and learn about the project.

The next marker he hopes to create before he puts a focus on Samantha Plantin will be about Cornelius Thornton, who was removed from slavery by two white New Hampshire soldiers in Fredricksburg, Va.

He went to public school in Manchester but died of what is now known as tuberculosis at age 14 in 1875.

A funeral at his home to pay respects was attended by many school children and their families and there is a marker for him in a Manchester cemetery.