By TERRY FARISH, InDepthNH.org

The Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire already knew it, the words of Elizabeth Dubrulle, director of education and public programs of the New Hampshire Historical Society.

Dubrulle said, “This is the time to be brave.”

JerriAnne Boggis, BHT Executive Director, and her staff opened their annual public conversation on democracy Sunday with bravery, by hosting a conversation on “Divisive Concepts: A Chilling Effect on Teaching History.” Covid limited attendance to 50 people, seated behind plexiglass wings at Portsmouth Middle School. Over 700 streamed in.

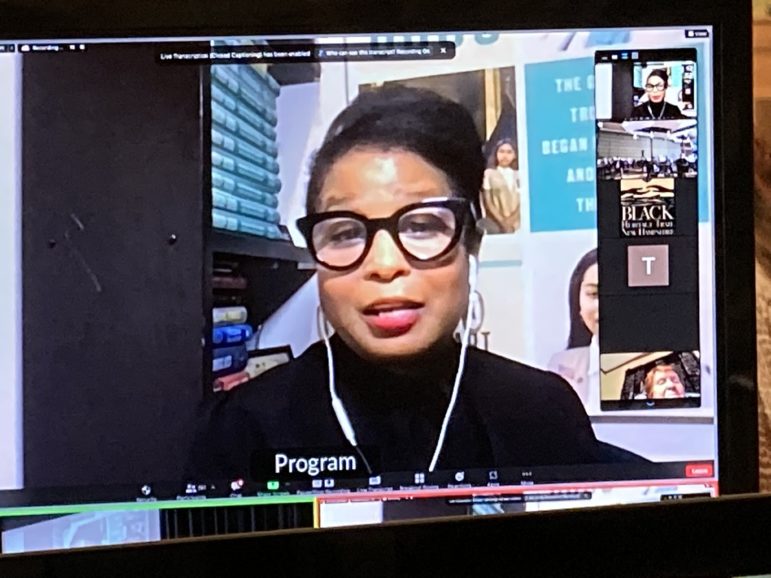

Panelists included Nikita Stewart, an editor at the New York Times and contributor to the 1619 Project, essays that first appeared in the New York Times Magazine that give historical context to the beginnings of slavery. Stewart was joined by Dubrulle, Erin Bakkom, 8th grade American history teacher at Portsmouth Middle School, and state Sen. David Watters, D-Dover.

The term “divisive concepts” draws on language in House Bill 544, sponsored by Rep. Keith Ammon, R-New Boston, Rep. Glenn Cordelli, R-Tuftonboro, and Rep. Jason Osborne, R-Auburn, and is also known as the bill on “prohibition of teaching discrimination.”

“Divisive concept” bill prohibits teaching that “An individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex; Any individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race or sex…”

The bill was tabled in the House. It was then amended and added as a trailer bill to the state budget in a proposal by state Sen. Jeb Bradley, R – Wolfeboro. Watters said that passing of the state budget by the Republican-controlled Senate was contingent on the inclusion of the amendment to “prohibit the teaching of discrimination.” This law seeks to regulate what can be taught and punishments to teachers.

“We’re talking about erasing any history of bad acts,” Nikita Stewart wrote.

Stewart said she wasn’t prepared for the intensity of the backlash to the 1619 Project. Some critics confused it with critical race theory.

“These were not radical ideas,” Stewart said. “They were simply gathered together. My essay for the project was called, ‘We are committing educational malpractice: why slavery is mistaught — and worse — in American schools.” (New York Times Magazine, Aug 19, 2019) “But now it’s, Why can’t we teach slavery at all, anywhere?

“Book bans are now on the table.”

The 1619 Project includes a picture book for young readers called Born on the Water with lines such as these:

It was illegal to teach enslaved people how to read,

but they birthed generations of

teachers and librarians,

scholars and authors.

from Born on the Water by Nicole Hannah Jones and Renee Watson

Dubrulle offered a long view of the diminishing social studies curriculum in New Hampshire schools. “Kids don’t know context of New Hampshire history to be able to put wars in chronical order. There’s almost no social studies” before high school. She said that because of testing requirements, teachers are forced to focus on English language arts and math. Today, teachers are more scrutinized than ever before in a subject that has the least support.”

Watters echoes these ideas. “There’s a diminishment of history being taught in the schools, from k-12. There’s less emphasis on the humanities and arts. In New Hampshire there’s so much history to be proud of concerning the struggles for freedom. The study of our Black history is a way to foster learning.”

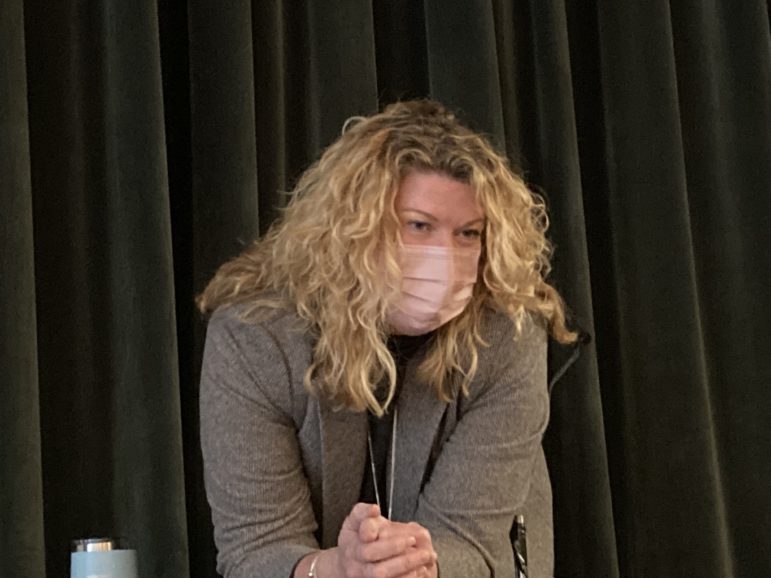

Erin Bakkom teaches inquiry-based research with her eighth-grade history students. “There are so many incredible primary sources. Kids have a lot to say. Kids are ready to hear what the truth is. They are ready to hear how history shapes us.” She said the legislation does not allow honest portrayal, only positive things.

Bakkom said that her students were interested in the impact of slavery in the north. That interest has led to student inquiries into New Hampshire in the 1960s, to integration of Wentworth by the Sea (Bakkom’s own scholarship) to the making of the film, Lost Boundaries, to ground breaking research done by Valerie Cunningham, founder of the Black Heritage Trail.

Bakkom said, “I didn’t expect this [prohibition of teaching discrimination] 23 years into my career.”

Stewart said, “It’s not guilt that [teaching history] seeks to develop. It’s about awareness.”

“Diverse Concepts” is the first in a series of the 2022 Elinor Williams Hooker Tea Talk series. Sen. Watters, also on the Board of the BHT, said, “The Tea Talks were always open conversations that were a mission of the Black Heritage Trail. The goal is to offer new insights on democracy. They offer a way to present history today.”

Watters said about the “divisive concepts” legislation: “We are facing a hiring crisis of teachers. New Hampshire used to be a magnet for teachers.” When he taught at the University of New Hampshire, he said, “I always encouraged students who wanted to become teachers. I told them, ‘I hope you’ll teach in New Hampshire.’ I can’t say that with confidence anymore. They could face lawsuits for what they say. They could lose their homes.”

What would he say to teachers in classrooms today?

Watters said, “Dig down deep to what brought you to your profession. Return to your own joy in learning. I hope the noise is not too overwhelming. I hope they know that most parents support them.”

“African American history is American history,” Watters said.

Stewart also said, “In my heart, I think we’re going to get through this.”

Tell us your story. Contact Terry Farish at terryfarishnh@gmail.com