By ARNIE ALPERT

Surprised to see a quotation from Martin Luther King, Jr. used more than once by advocates of the proposal to ban discussion of “divisive concepts” such as “race or sex stereotyping,” I re-read Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. I encourage supporters of HB 544 to do the same.

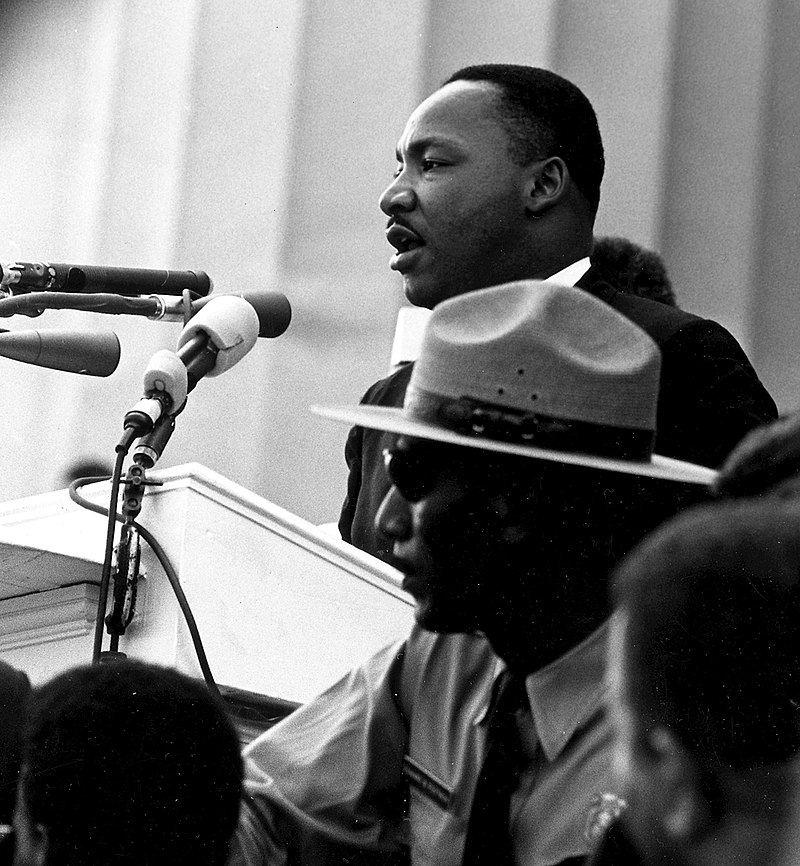

By most accounts, Dr. King’s speech was the highlight of the 1963 March for Jobs and Freedom, now remembered as the “March on Washington.” Inspired by A. Phillip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the rally marked the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation which ended slavery in the states of the Confederacy. It took place shortly after demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama brought inescapable attention to the brutality needed to maintain racial segregation. By emphasizing jobs and freedom, the march sought to advance an agenda for job training and an end to workplace discrimination as well as voting rights and a civil rights bill that would end segregation in schools and public accommodations. Dr. King was one of several major speakers.

A century after emancipation, Dr. King began, “the Negro still is not free; one hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.” Today, we might label that, “systemic racism.”

Dr. King continued with reference to the Declaration of Independence, which he saw as a promise that all Americans, regardless of race, were entitled to the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. In effect, he said, the founders of the nation had issued “a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.”

“It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned,” he charged, saying that instead of following through on a promise, America had issued a bad check. “We’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice,” Dr. King said. Today, we might label that a call for reparations.

Seeking to rescue the nation from “the quicksands of racial injustice,” including “the unspeakable horrors of police brutality,” Dr. King said “There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.”

Today we might just say, “Black Lives Matter.”

Yes, Dr. King said he had a dream that “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by content of their character.” It is that line, 29 words out of a 1642-word speech, which is especially popular with backers of HB 544, now incorporated into the budget trailer bill adopted by the NH House of Representatives and pending in the Senate. The “divisive concepts” proposal, based on a Donald Trump executive order, seeks to prohibit tax dollars from being spent on training programs which address the systemic nature of racism and sexism. A previously obscure academic concept known as “Critical Race Theory,” or CRT, has drawn the ire of HB 544 backers, though the term itself appears nowhere in the proposal’s language.

At a pro-HB 544 rally held at the State House in April, one person reportedly carried a sign reading, “Teach MLK not CRT.” A writer who calls herself “Barbara from Harlem” addressed the same rally, where she labelled CRT “racist” and said, “The correct path (to King’s dream) is to judge people by the content of their character, not the color of their skin.” Dr. Elana Yaron Fishbein, founder of a group which has paid for pro-HB 544 display ads in local newspapers calls Dr. King’s teachings “wholesome” and “uplifting,” in contrast to what she calls “radical indoctrination” in schools that teach lessons emphasizing diversity and anti-racism.

In a column titled “Critical Race Theory Is Dangerous. Here’s How to Fight It,” published in the conservative National Review, Samantha Harris writes, “We need to fight the rise of this toxic and destructive orthodoxy if we want America to be a place where, as Martin Luther King said, our children are judged by the content of their character and not the color of their skin.”

And in an opinion column published in the Concord Monitor on April 21 and the Union Leader on May 11, Joseph Mendola backs HB 544 and says, “CRT rejects the work and idea of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. that says ‘Judge the people by the content of their character, not the color of their skin.’ CRT theorists call King’s idea dangerous. That is toxic thinking. America has been moving in that direction of Dr. King’s idea for the last 50 years. We want to teach our children and share with our employees that we want to act in the way Dr. King has prescribed, not the CRT idea of systemic racism.”

But today, we might call Dr. King a critical race theorist. He knew, after all, that discrimination had been baked into American law and custom from the beginning and that it wasn’t just the fault of misguided individuals. He wanted to “transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood,” but he never denied the existence of discord or its systemic nature.

Yes, Dr. King had a dream, but he was wide awake at the March on Washington when he called for dramatic protests against racism to continue. Speaking prophetically, he said, “We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

If we want to learn about Dr. King’s teachings, the “I Have a Dream” speech is a good place to start, as long as we study the whole thing. Then, we can move on to some of the thousands of other speeches he gave in his shortened career and to any of the books he wrote. Considering the body of his work, words, and deeds, it’s hard to place Martin Luther King, Jr. in alignment with those who want to forbid discussion of systemic racism. Instead, we should revisit his call to “let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire” and emulate his insistence that we look critically on the contrast between America’s highest ideals and the reality of violence and discrimination faced by people of color. As Dr. King well knew, ending racism takes ongoing action, not just dreams.

From 1988 to 2000, Arnie Alpert served as Communications Coordinator for the campaign to establish a New Hampshire state holiday named for Dr. King.

Quotations from “I Have a Dream” taken from A Testament of Hope: the Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., edited by James W. Washington.