By D. Maurice Kreis

What would you pay to keep your baby alive and thriving into adulthood?

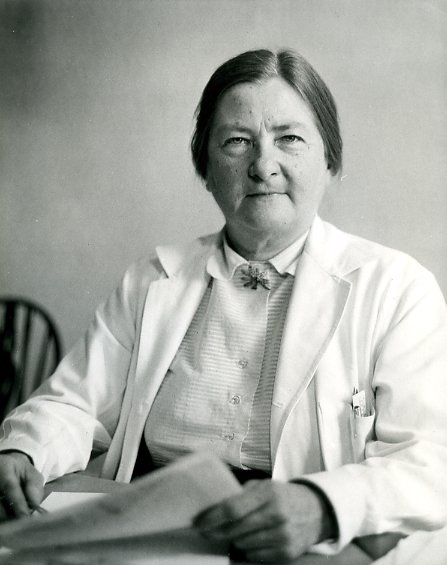

That’s not a question I get paid to ponder as New Hampshire’s ratepayer advocate, but it’s been on my mind. So, in keeping with my intermittent holiday tradition of devoting my last column of the year to a topic that touches me personally, I’d like to introduce you to Dorothy Hansine Andersen.

She is not a baby. In fact, Andersen she died in 1963 at the age of 61 after a distinguished career as a pathologist at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in New York.

Dr. Andersen was a gifted physician who earned a doctorate in endocrinology on top of her M.D. But, the times being what they were, by virtue of her gender Dr. Andersen was thwarted in her efforts to practice on live patients and was consigned instead to examining dead ones, in the pathology lab.

A particularly sad task for Dr. Andersen was performing autopsies on babies who had died. And, as she did that grim work in the basement of her Manhattan hospital, she began to notice a pattern in some of the tiny human bodies she was examining.

Specifically, she noticed cysts on the pancreases and lungs of certain babies. In 1938 Dr. Andersen published an account of her findings and invented a name for the phenomenon she had observed: cystic fibrosis.

Before 1938, what we now know as cystic fibrosis was just a mysterious reason some babies – ones whose skin was salty to the taste – died early in life. Today there are more than 30,000 people in the U.S. who are living with cystic fibrosis. Every single one of those people owes their life to Dr. Andersen.

One of them is my daughter, who turned 18 a month ago.

My purpose in taking up this subject today is not to brag about my daughter, though any college admissions officers who happen to read this column should be advised that Rose is academically accomplished, hilariously funny, a gifted dressage rider with Olympic aspirations, and endowed with the kind of insight, resilience, flexibility, persistence, and wisdom that are necessarily cultivated by anyone who manages to thrive in the face of a serious chronic illness like cystic fibrosis.

Rather, my point is that the cost of keeping those 30,000 people alive is something we as a society simply did not incur before 1938. And the cost is growing – thankfully so, because science and medicine are advancing, new treatments are emerging, and the median survival age for people with CF is steadily increasing.

Multiply that by all of the similar advances in the care of other diseases and you understand why the cost of healthcare is escalating and accounting for an ever-increasing share of the economy.

Recently the Food and Drug Administration approved a new cystic fibrosis drug, called Trikafta. Developed by Boston-based Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Trikafta joins a suite of similar drugs, also developed by Vertex, that are the first ones to treat the underlying cause of CF at the cellular level. Collectively, the Vertex therapies are now approved for use by 90 percent of people with cystic fibrosis.

The price tag for a year of Trikafta: $311,000 per year.

That’s a jaw-dropping sum, until you remember the question with which I began this column.

Here’s where I can put my ratepayer advocate hat back on. Unlike prices for electricity or natural gas, drug prices are not regulated (yet). But the same principles used to develop just and reasonable utility rates can be brought to bear on whether it is appropriate to charge $311,000 a year for a drug.

A bedrock principle is that it is reasonable for investors to demand a higher return as the riskiness of their investment increases. Utilities are a low-risk investment, as I repeatedly find myself reminding utility management.

Pharmaceuticals by contrast are ultra high-risk. Most drug research does not pan out and even therapies that gain approval must persist through long and expensive trials. Sorry, Senator Sanders, but it is actually quite reasonable for the owners of Vertex Pharmaceuticals to expect a big return on the investment they made in drugs like Trikafta.

What we need is transparency. Allowing Medicare (the nation’s biggest purchaser of pharmaceuticals) to negotiate prices with drug companies is also a welcome idea. Congress is considering some promising legislation on this front – notably H.R. 3, the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs NowAct recently approved by the House.

However, federal drug price reform will be a setback for patients unless there are provisions protecting their access to life-sustaining drugs like Trikafta. Families dealing with life-shortening chronic illness should not bear the burden in the event the federal government and drug makers cannot agree on a price.

That’s not to let Vertex off the hook. Last year the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) – an independent nonprofit that works as a kind of self-appointed rate commission to study drug prices and treatment costs – issued a detailed report on the Vertex CF drugs that were then available. Among the experts with whom ICER consulted was Dr. Brian O’Sullivan of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, a fabulous pulmonologist. (I know he’s fabulous because he’s among the CF doctors who have treated my daughter.)

ICER accused Vertex of “harming patients and families” and “benefiting from monopoly power.” According to the institute, Vertex should “[a]bandon vague claims that prices are justified by the need to invest in future research and instead join the growing number of biotech innovators who provide a transparent, explicit justification for their prices based on the ability of treatments to improve the length and quality of patients’ lives.”

This discussion is especially bittersweet for me, since my daughter is among the ten percent of CF patients who do not benefit from Trikafta or the other Vertex drugs now on the market. My family is implicated because the CF Foundation, which invested in the Vertex drugs when they were under development, cashed out is share of the royalties in 2014 to the tune of $3.3 billion. That money is helping to pay for research that will, in due course, cure the disease for everyone who has it.

Meantime, I remain grateful for the life of CF heroes like Dorothy Hansine Andersen. And mindful of all of the sorrows and ironies. Though she discovered cystic fibrosis and thus did so much to improve the pulmonary health of so many, Dr. Andersen was a chain-smoker.

She died of lung cancer.