By Christopher Jensen

MILAN — Early next month, a 22-year-old ski champion and an 80-year-old ski jump that was abandoned in 1985 are expected to make a high-flying comeback together.

The skier is Sarah Hendrickson. She was born about nine years after the 1985 closing of the Nansen ski jump, a 171-foot steel tower that overlooks Milan, a town of 1,300 people on the Androscoggin River in Northern New Hampshire.

Hendrickson was the 2012 World Cup champion, but then suffered a serious leg injury in 2015. She has since returned to competition and is aiming at the 2018 Winter Olympics.

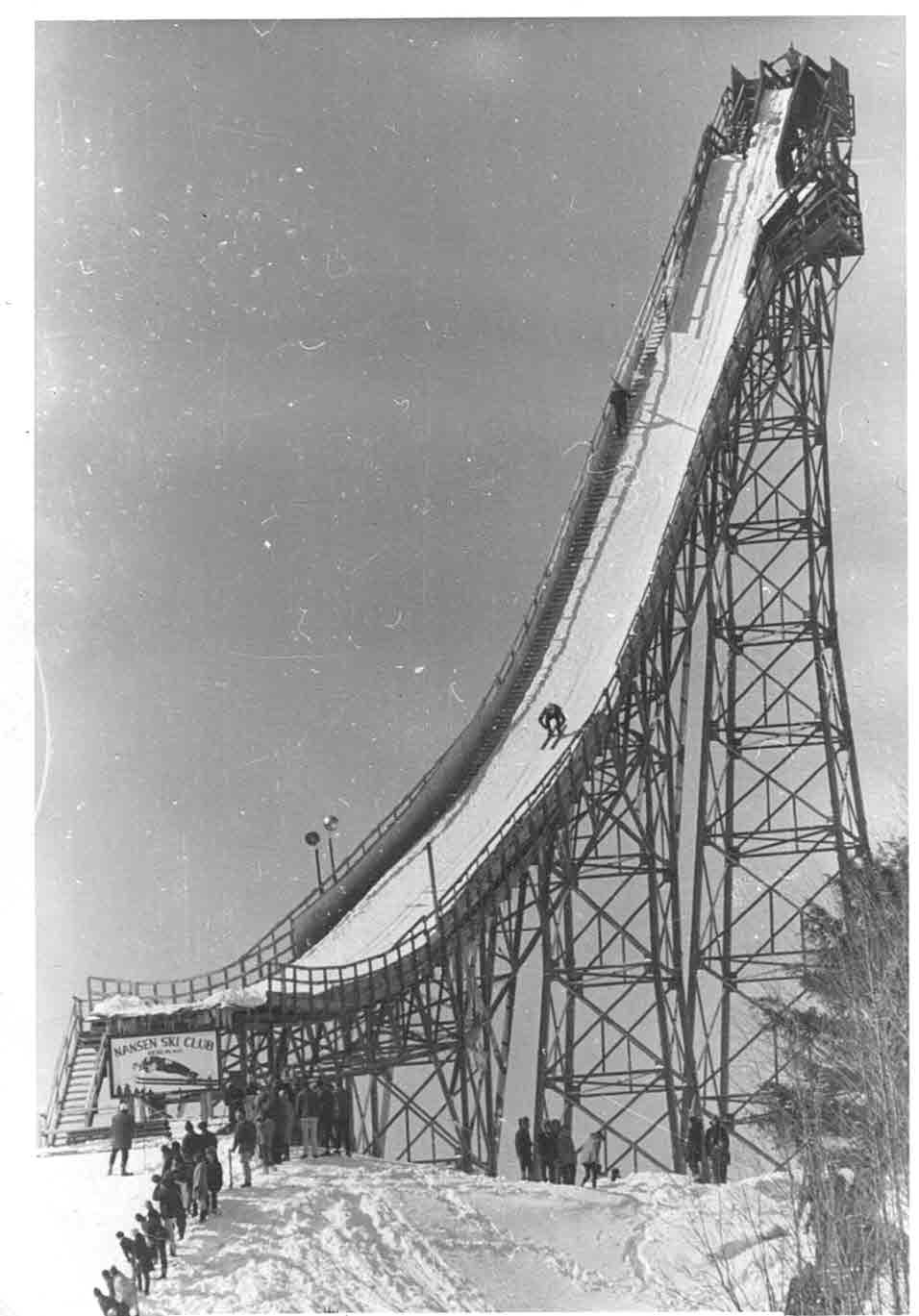

Her inanimate partner, the Nansen ski jump, was built during 1936 and 1937. It was a community effort led by ski enthusiasts and was used for the 1938 Olympic tryouts.

“At the time it was the largest free-standing ski jump in the world. Other jumps were built on the side of a hill or mountain. It was all made out of steel,” said Walter Nadeau, the vice president of the Berlin and Coos County Historical Society.

The 1938 event attracted about 25,000 spectators and was broadcast on 87 radio stations nationwide, according to Nadeau. There was a campaign to make it part of the 1944 Winter Olympics, a hope extinguished by World War II.

Jumping at Nansen was exhilarating, said Bob Arsenault, 88, of Bethlehem, who started competing at Nansen in 1947, when he was in high school.

“I have a little bit of acrophobia so standing at the top of the tower, especially it if was windy, I got a little bit frightened,” he said. “But once I started down the jump it was sheer ecstasy. Being airborne. Being in control of your flight.”

Sarah Hendrickson, Photo by Mirja Geh / Red Bull Content Pool

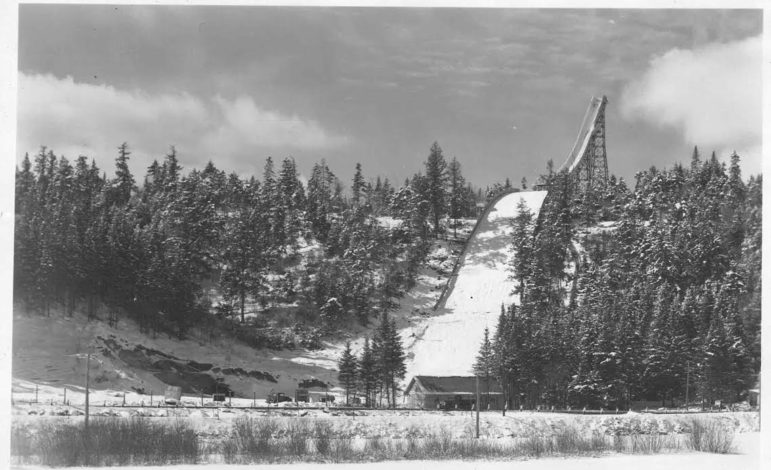

The last competition was held in 1985. Competitors were drawn to newer ski jumps and there weren’t enough volunteers to maintain the metal structure and 310-foot wooden runway, Nadeau said.

Once a source of regional pride, the jump was abandoned, increasingly hidden by trees and brush and lost in foggy memories. It didn’t even register with some locals as they drove along the adjacent Route 16.

“The significance of it was lost for a few generations,” said Jay Poulin, the secretary of the Friends of Nansen Ski Jump.

Hendrickson and Nansen connected when Red Bull, the energy-drink company that sponsors Hendrickson, heard about the ski jump being resurrected as a tourist attraction, said Ben Wilson, the director of the state’s Bureau of Historic Sites.

Red Bull asked her to jump so it could make a video.

“The restoration of Sarah and the restoration of the ski jump. So, lots of good warm and fuzzies,” Wilson said.

The state had already come up with $150,000 to fix up the structure and Red Bull added about $75,000, Wilson said.

Hendrickson said she loves the history of ski jumping and jumping at Nansen is a chance to experience a bit of it.

“For me it’s a fun way to take my mind off the competitive season and just kind of enjoy ski jumping for what it is,” she said.

Her home is in Park City, Utah but her family once lived in New Hampshire and they knew about Nansen.

“I think the funniest part is that when I was talking to friends and family that lived in the area back there they were like ‘Oh, my gosh. You’re going to jump that hill. That jump is insane.’”

Hendrickson visited the tower in November and was not worried. She competes on bigger jumps.

“When I first saw it, it actually looks small to me. It is smaller than the normal jump. It was just kind of funny because people see the tower and immediately get freaked out,” she said.

Courtesy of the Berlin Coos County Historical Society

The first time the Nansen jump was used was for the tryouts for the 1938 Olympics. Courtesy of the Berlin Coos County Historical Society.

But jumping from Nansen will be different because it has a “high-flying” design, said Jeff Hastings. He competed at Nansen in 1979 while at Williams College and in 1984 went on to take fourth place in the Winter Olympics at Sarajevo.

Contemporary ski jumps are designed so that the skier leaves the jump and then flies fairly close to the contour of the ground before landing. But that wasn’t the case at older jumps such as Nansen, according to Hastings.

“The old school was more pop you out there and let you come down, if you can. It is more exciting because you go way out there and then you are falling more instead of cruising over the ground,” he said. “I think she’ll have a fun jump.”

But she won’t be the first off the renovated jump.

Hendrickson said a younger skier from the junior team – who is about Hendrickson’s height and weight – will do a test jump. That will give Hendrickson’s coach a chance to gauge factors like speed and distance.

“Obviously we will take it just as safe with her, but she is used to jumping these older style hills because she is from the Midwest,” Hendrickson said. “So, she will kind of know what to expect. It gives me a little sigh of relief that I don’t have to be the first one to go off,” Hendrickson said.

The date of the jump hasn’t been disclosed, although the first week in March is the target. A major factor will be the weather. And Red Bull won’t be making any public announcement. It considers the event private.

It is similar to a movie being shot on any other state-owned property, said Wilson, the state official.

“It is way too complicated of an event to make public,” said Red Bull spokesman Michael Crocco.

But Wilson said there may be future events that would be open to the public and people will be able to visit the site after the jump.