Lobbying by prosecutors and police guts law that would have punished prosecutors who didn’t share evidence with defense. Debate cited case of Fred Steese, subject of ProPublica and Vanity Fair story.

Two Nevada laws designed to counter bad behavior by state prosecutors, or at least give some defendants the ability to undo troubling plea agreements, passed last week, although one was substantially gutted under pressure from prosecutors and police.

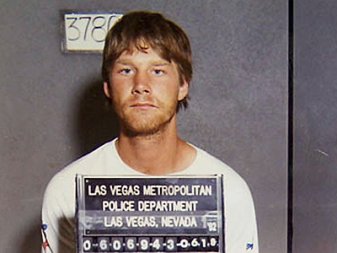

The legislative debate over both laws mentioned the case of Fred Steese, a drifter wrongfully convicted of murder, then declared innocent more than 20 years later by a judge after exculpatory evidence was found in the prosecution’s files. The prosecution then pressured Steese to agree to a controversial deal called an Alford plea that allowed him to say he was innocent and go free as long as he pleaded guilty.

The bill that passed after being substantially watered down was AB376. If passed as originally drafted, it could have exacted penalties for the sort of misconduct that led to Steese’s conviction. It would have required prosecutors to share evidence with the defense 30 days prior to trial or risk exclusion, broadened the scope of favorable evidence they are required to share and mandated that courts dismiss charges when prosecutors showed bad faith in failing to turn evidence over.

The bill that passed after being substantially watered down was AB376. If passed as originally drafted, it could have exacted penalties for the sort of misconduct that led to Steese’s conviction. It would have required prosecutors to share evidence with the defense 30 days prior to trial or risk exclusion, broadened the scope of favorable evidence they are required to share and mandated that courts dismiss charges when prosecutors showed bad faith in failing to turn evidence over.

Much of the draft law simply reinforced major U.S. Supreme Court constitutional rulings — such as Brady vs. Maryland — which apply nationwide and hold that turning over evidence favorable to the defense is a matter of civil rights and failing to do so violates a person’s right to due process. The Nevada law would have made penalties more uniform and a matter of course.

Supporters of the legislation, including the Clark County Public Defender’s office, said preventing wrongful convictions like Steese’s was one of the goals of the proposed law.

But Christopher Lalli, a top assistant with the Clark County District Attorney’s office, argued at an April hearing that the bill was “unreasonable” and a “radical change” that would “unduly burden prosecutors.” When an assemblywoman asked him what ramifications the prosecutors faced in Steese’s case, Lalli responded, “Ramifications for what?”

Lalli, who is on the disciplinary board for the State Bar of Nevada, said he was “very involved” in the Steese case and claimed “there was no exculpatory evidence withheld.”

Without mentioning that a judge had granted Steese a rare order of “actual innocence”’ or that the prosecutors’ office responded by pressuring Steese to take an Alford plea or face a retrial, Lalli noted that Steese had pled guilty to second-degree murder charges — “hardly something that would be done by somebody who was actually innocent.”

Kafka in Vegas

Fred Steese served more than 20 years in prison for the murder of a Vegas showman even though evidence in the prosecution’s files proved he didn’t do it. But when the truth came to light, he was offered a confounding deal known as an Alford plea. If he took it he could go free, but he’d remain a convicted killer. Read the story.

Fred Steese served more than 20 years in prison for the murder of a Vegas showman even though evidence in the prosecution’s files proved he didn’t do it. But when the truth came to light, he was offered a confounding deal known as an Alford plea. If he took it he could go free, but he’d remain a convicted killer. Read the story.

Following the hearing, only a small portion of the bill survived — a requirement that prosecutors press charges within 72 hours against defendants in custody.

Lisa Rasmussen, a director for Nevada Attorneys for Criminal Justice, said prosecutors’ failures to share evidence with the defense have been an ongoing problem in the state and it was “really depressing we could not get more reform this [legislative] session.”

But a second bill, inspired by Steese’s case and others like it, received a more favorable reception.

Rasmussen said she realized the raw deal Steese had gotten in 2013 and tried to help him withdraw his Alford plea so that he could sue for wrongful conviction. But Nevada law didn’t allow him to take back his plea. Last week, Nevada’s governor, with the support of prosecutors in the state, signed a new law that allowed certain defendants to undo plea agreements. The law, however, comes too late to help Steese, Rasmussen said.

“What happened to Fred makes me so mad,” she said. “We’re filing an application for a pardon.”