Power to the People is a column by D. Maurice Kreis, New Hampshire’s Consumer Advocate. Kreis and his staff of four represent the interests of residential utility customers before the NH Public Utilities Commission and elsewhere. It is co-published by Manchester Ink Link and InDepthNH.org and distributed as a public service to news outlets across the state.

By D. Maurice Kreis, NH Consumer Advocate

Garry Rayno is right, as usual.

As one might expect from a journalist who has been writing about energy and other contentious New Hampshire topics for three decades, the InDepthNH.org reporter drew the right conclusion in his July 21 column about the recent decision of the New Hampshire Supreme Court about the Northern Pass transmission project.

The state’s highest court affirmed the decision of the Site Evaluation Committee to reject the controversial power line that would have sliced through New Hampshire to deliver massive quantities of hydroelectric power from Quebec to greater Boston. Rayno’s conclusion: What New Hampshire and the rest of New England need is a “true regional approach to electricity, beyond the Independent System Operator system controlled by the power generators.”

Rayno is referring to ISO New England – which, in the parlance of federal energy law, is technically a “regional transmission organization” (RTO) even though ISO does indeed stand for “independent system operator.” The distinction is important because RTOs have more authority and more independence than ISOs do.

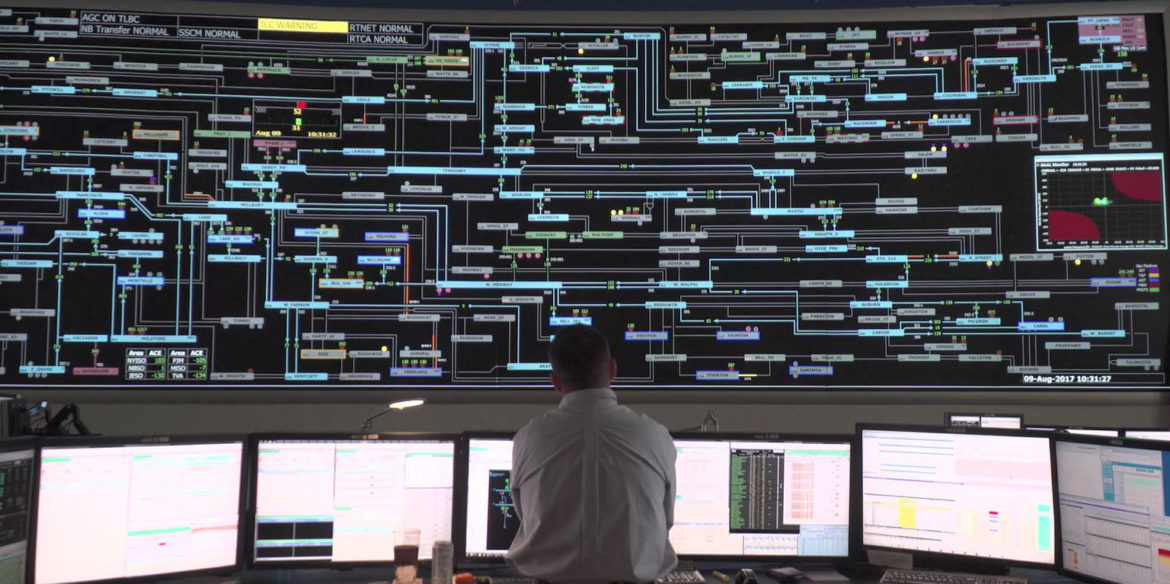

ISO New England is a nonprofit organization that has been tasked by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to discharge key functions for all six New England states. First and foremost, the RTO operates (but does not own) the bulk power transmission system. That means ISO New England is our major bulwark against major, cascading power failures.

Another critical ISO New England function is overseeing the open wholesale markets by which electricity is bought and sold throughout the region. Once upon a time, electric utilities were vertically integrated, meaning they owned everything – including generation plants. Now the electricity produced by generators is considered a free-market item even though wholesale power prices are still subject to FERC regulation under the Federal Power Act.

That’s not good enough, according to Rayno.

He wants New England “to look at electricity in the same way the Northeast viewed carbon emissions when former New York Gov. George Pataki spearheaded the regional effort to cut greenhouse gases called [the] Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative or RGGI.” Rayno points out that New England has some of the highest electric rates in the country and so he calls for “joining together to try to stabilize and reduce the state-to-state cannibalization of neighboring states’ landscapes.”

Such cannibalization was a fair allegation against Northern Pass, since all of the power would have been sold in hydropower-thirsty Massachusetts (and, in fairness, the project would have been entirely paid for by customers in the Bay State). There would have been some modest, region-wide wholesale price reductions, but New Hampshire will now get the same benefits without any local impacts (assuming that Plan B for Massachusetts, the equally controversial NECEC transmission project across Maine, is built instead of Northern Pass).

Unfortunately, Rayno’s plea to our altruistic rather than cannibalistic instincts faces a formidable obstacle: the U.S. Constitution.

The framers did not provide for regional authority; we have only a national government and 50 sovereign states. The only exception is the Constitution’s “interstate compacts” clause. Basically, states can make treaties with each other, but it requires congressional approval. An interstate compact creating a regional energy authority for New England seems unlikely in the present political climate.

We do have the Federal Power Act, but it explicitly leaves to individual states the responsibility to decide what kinds of generation facilities get built within their individual borders. Under the federal statute, only wholesale energy prices, and interstate transmission, are regulated by the FERC.

This is why the FERC did not require utilities to surrender control of the power grid to RTOs – indeed, in the southeast, there is no such thing – but, instead, simply encouraged the utilities (and their states) to go along with such arrangements. Ergo, ISO New England is a relatively weak confederation, and one whose governance is subject to a system of stakeholder input so byzantine as to be truly worthy of ancient Byzantium.

Therefore, the pathway to the “true regional approach” urged by Garry Rayno is by getting the FERC to force ISO New England to be a more dynamic organization that is less vulnerable to the kind of conventional thinking that legacy generators and transmission owners promote.

In that regard, attorney David Ismay of the Conservation Law Foundation recently made an interesting presentation to the FERC about ISO New England. He had the good luck to be presenting after ISO New England did.

When ISO New England had the floor, they put two graphs up on the screen, one above the other. One showed that pipeline gas was dangerously scarce during key hours of the infamous cold snap that occurred from December 25, 2017 to January 8, 2018. The other graph showed that wind power generation during that period was variable.

Ismay simply drew some green lines between the two graphs to show that the wind power, though variable, tended to be available during exactly those hours when the natural gas generation was limited due to fuel constraints. “Fuel diversity brings fuel security,” Ismay concluded.

That’s good news for ratepayers, even ones who don’t care about renewable energy. It suggests that emerging technologies and a diverse portfolio can mean lower rates and good reliability.

Ratepayers need more good news from ISO New England. For example, it’s time to do away with the ISO New England capacity market, an elaborate mechanism designed to shovel so-called “missing money” to big generators that use nuclear energy and natural gas. ISO New England should stop tinkering and start euthanizing that one.

Ending the capacity market would likely require lifting the current cap on wholesale energy prices – since the cap is where the missing money goes missing. That could be disruptive, but perhaps an inducement to the kind of regional cooperation for which Garry Rayno yearns.

Ultimately, Rayno Regionalism would require reinventing ISO New England in a manner that only a muscular and vigilant FERC can require. The five-person commission will soon be down to three members with the impending departure of the only New Englander on the FERC, Obama-era appointee Cheryl LeFleur.

Will the FERC vigorously assert the public interest, which demands regionalism and innovation? Or will New England remain balkanized and captive to old ways of thinking about energy? Here’s hoping it’s the former and not the latter.