By DAMIEN FISHER, InDepthNH.org

The man the state of New Hampshire sent to investigate claims five-year-old Harmony Montgomery was being abused, before he dismissed the case, was twice removed from his positions during his career amidst alarming behavior, according to records obtained by InDepthNH.org.

But despite at least one known conviction for domestic violence, later annulled, and a separate complaint over sexual harassment, Demetrios Tsaros of Pembroke managed to stay employed by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services.

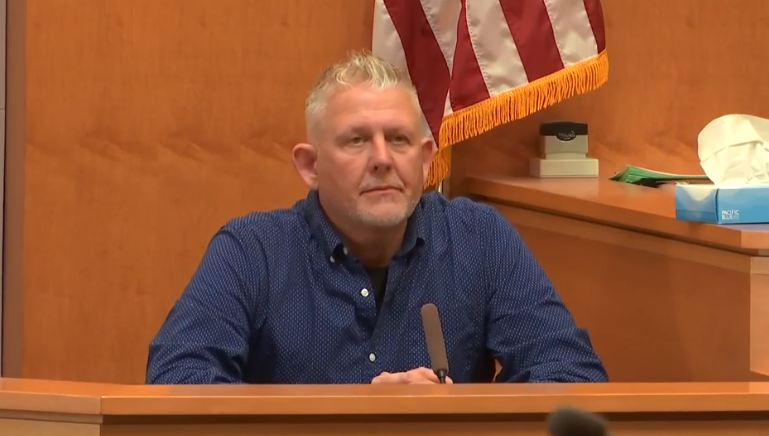

Contacted Monday, Tsaros denied initially he had been fired in the past. When he testified at Harmony’s murder trial, he said he left the state in September of 2021 and was working for the U.S. Postal Service.

“I don’t even know where you’re getting that,” Tsaros said.

When told InDepthNH.org obtained records from the state Personnel Appeals Board and the Police Standards and Training Council about his past employment history, Tsaros brought the conversation to a close.

“I don’t want to discuss this anymore,” Tsaros said.

Tsaros is central to the lawsuit brought by Harmony Montgomery’s mother, Crystal Sorey. As a child protective service worker with the Division for Children, Youth and Families, Tsaros was tasked in the summer of 2019 to investigate a report that the five-year-old girl was being abused by her father, Adam Montgomery.

According to the lawsuit, Tsaros failed to interview Harmony and Adam Montgomery for weeks after the report was made that the girl had been beaten and given a black eye. Though he later reported seeing faded bruising and redness around the girl’s eye, Tsaros didn’t speak to the girl, contact police, or take any other action to protect her, the lawsuit states.

Adam Montgomery was convicted this year in Harmony’s cruel and violent murder, which took place in December of 2019.

Retired Massachusetts judge and author, Carol Erskine, whose book Cruel Injustice covers Harmony’s story, did not know about Tsaros’ history before being contacted by InDepthNH.org. She was astounded Tsaros was in his position at DCYS at all.

“The notion you have a state moving a person who has prior domestic violence charges against him from agency to agency is shocking to me,” Erskine said. “Here is this tiny, little, beautiful girl who was supposed to be protected by the New Hampshire child protection system, and it is beyond sickening to learn her so-called protector has a history of violence.”

InDepthNH.org has learned the 2001 domestic violence conviction was annulled. Under New Hampshire law, annulled convictions do not show up on background checks as they are considered not to exist once the annulment goes through.

Blair and Johnathon Miller, the adopted fathers of Harmony’s brother, Jamison, said in a statement to InDepthNH.org that Tsaros’ employment history is another illustration of the many ways New Hampshire and Massachusetts authorities failed Harmony.

“There’s no excuse for how these agencies failed to protect Harmony Montgomery and continue to fail to protect other children. The fact of the matter is no one was looking out for Harmony. NO ONE,” the Millers wrote.

According to Sorey’s lawsuit, Tsaros found the Montgomerys living in a filthy house without heat or electricity, where food rotted, and was littered with drug paraphernalia. Tsaros reported that both Kayla and Adam Montgomery claimed their house guest was in relapse, but they were clean.

Tsaros did speak to Kayla Montgomery a week after the alleged beating, but he did not speak to Harmony, or to Adam Montgomery. That did not stop Tsaros from telling Manchester Police there was nothing to worry about.

“Following this visit, Tsaros noted in the Contact Log that he sent an email to the Manchester Police Department stating that ‘…I think you folks are all set. I saw the children and did not observe any bruises, marks, etc…,’” the lawsuit states.

According to the documents obtained by InDepthNH.org, Tsaros worked for the state Department of Health and Human Services from 1995 to 2021, though in three different capacities. He was a police officer with the New Hampshire Hospital Campus Police Department, until his police certification was surrendered due to the domestic violence conviction. He was then a youth counselor for the Sununu Youth Services Center, formerly known as YDC, and remained one even after he was fired after a sexual harassment investigation. Finally, he went to DCYF as a child protection service worker.

In February of 2001, Tsaros was discharged from the Hospital Campus Police through a negotiated resignation after a domestic violence incident then pending in Franklin District Court, according to correspondence on file with the New Hampshire Police Standards and Training Council.

Tsaros later pleaded no contest to one count of obstructing the report of a crime, and one count of simple assault, according to PSTC meeting minutes. The minutes state that the convictions would be dismissed from Tsaros’ record after two years if he met conditions of good behavior set by the court and sought counseling.

Deputy Chief Don Palmer told then-PSTC Executive Director Earl Sweeney there were red flags about Tsaros prior to that domestic violence case and that he had “a past history of this sort of problem,” according to notes Sweeney placed on file in 2001.

Sweeney’s interdepartmental note, part of the PSTC file kept on Tsaros, misspells the last name by dropping the final “s.”

“Tsaro came to work last year with a cast on his hand and admitted to Palmer he became angry at home and smashed his hand into a wall,” Sweeney wrote. “Palmer believes there was a prior domestic violence incident a couple of years ago in Concord involving Tsaro, the record of which he thinks has since been expunged. Palmer said Tsaro is not a particularly good employee, and he feels he has little respect for women.”

In October of 2001, Tsaros went before the Police Standards and Training Council and agreed to surrender his certification rather than have it revoked, according to meeting minutes. The surrender kept open the possibility Tsaros could regain his certification after two years as long as he underwent an anger management course. Tsaros had completed six months of batterer’s counseling at that point in October of 2001, according to the minutes.

The PSTC voted in a non-public 2010 meeting to restore Tsaros’ certification, though the minutes of that meeting have not yet been made available. Despite that vote, InDepthNH.org confirmed through PSTC that Tsaros did not get another job in law enforcement after his certification was restored.

The same month Tsaros surrendered his police certification, he began a new job as a YDC, now known as the Sununu Youth Services Center, youth counselor. That position, like the Hospital Campus Police job, was again under the umbrella of DHHS. While the domestic violence conviction would later get annulled, it should have shown up on his record when he got the YDC job. DHHS’s Jake Leone did not respond to a request for comment about Tsaros’ employment history.

Tsaros wasn’t with YDC long before he got into trouble again, according to records on file with the Personnel Appeals Board. In May of 2002, Tsaros was reported for making sexually harassing comments to a female YDC co-worker, according to documents filed with the PAB.

The investigation into that complaint resulted in a finding that Tsaros made several harassing comments and he was fired for violating DHHS policy.

“It was determined that your behavior created an intimidating, hostile or offensive working environment,” DHHS Human Resources Administrator Susan Anderson wrote in the July, 2002 termination letter.

But Tsaros and his SEIU union representatives appealed the firing, arguing that of the six alleged comments, only two occurred that could meet the policy guidelines as being sexually harassing, and only one was made directly to the complainant. Tsaros maintained, however, he did not do anything to warrant being fired.

“Mr. Tsaros denies making any comments whatsoever that rise to the level of an action for which he could be terminated and denies any comments that rise to the level of sexual harassment,” the SEIU appeal letter states.

Before the PAB got the full case, Tsaros reached a settlement with the state Department of Health and Human Services and withdrew his appeal in September of 2002. His employment records indicate he remained on the job for several more years before moving to become a child protective service worker with DCYF in 2011, another agency that is part of DHHS. Tsaros would remain at DCYF until 2021.

Even with his annulled criminal record and negotiated settlement over the sexual harassment complaint, his supervisors likely knew about his history as he changed divisions, Erskine said.

New Hampshire’s understaffed DCYF has struggled in the past to keep up with the cases it is assigned. Tsaros had been there for almost a decade when he was tasked with investigating the Montgomery abuse allegation, and Erskine wants to know if he disclosed his conflict of interest in the matter to his supervisors.

According to Sorey’s lawsuit, Tsaros was Adam Montgomery’s youth counselor at YDC, a fact that should have disqualified him from handling the abuse report, Erskine said. In fact, according to the Sorey lawsuit, Tsaros relied on his prior relationship with Adam Montgomery while he handled the abuse assessment.

When Kevin Montgomery, Adam Montgomery’s uncle and the person who reported the abuse, called to report Adam Montgomery was back to using heroin, Tsaros did not believe it, the lawsuit states.

“Kevin [Montgomery] reported that Tsaros told him that he had known Adam since Adam was 15 and that Tsaros knew he was ‘not like this,’” the lawsuit states.

At one point, Tsaros reportedly told Adam Montgomery’s family he should never have been assigned to the case because he knew Adam Montgomery from YDC, the lawsuit states. The lawsuit alleges Tsaros never talked to Harmony alone, never talked to witnesses, failed to pursue issues like the fact Harmony was not enrolled in school, or that Adam Montgomery was violating a visitation order.

After having the file for three months, as is standard DCYF procedure, Tsaros closed the investigation as “unfounded.” Harmony would be dead six weeks later.

“In my mind, (the abuse investigation) might have been Harmony’s last chance to be rescued and live, if DCYF and its supervisors had done their job correctly,” Erskine said. “Everything that could go wrong with Harmony did go wrong with Harmony.”

The Millers want to see real change come to the way New Hampshire and Massachusetts administer their child protective agencies and worry about what will happen if there is no meaningful turnaround.

“The reality is, there could be another Harmony Montgomery happening right now and nothing has been put in place to prevent it from happening. How many children have been lost and what’s it going to take for laws to change?” the Millers wrote. “Our son Jamison will grow up hearing how no one was there to protect his sister; a sister who was looking out for him when they were in foster care together. No one protected his sister against murder, especially the people put in place to protect her. We won’t stop fighting for change until someone realizes what can be done differently to protect children who truly need it most.”