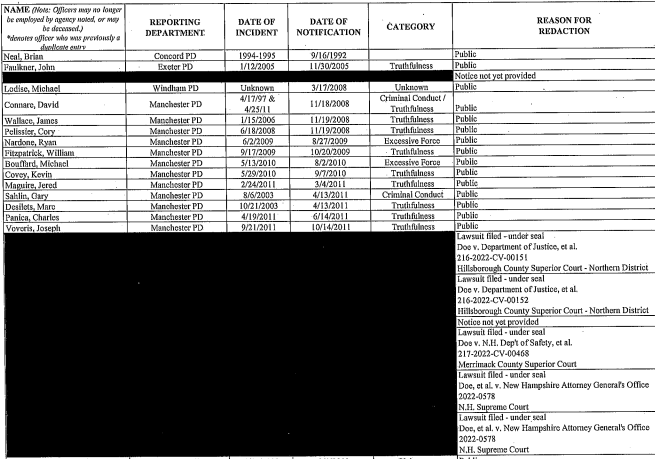

The most recent Laurie List of dishonest cops can be seen here: https://indepthnh.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/November-5-2024-EES-List.pdf

By DAMIEN FISHER, InDepthNH.org

One police officer accused of lying is getting removed from the state’s Exculpatory Evidence Schedule, while another accused of lying will remain on the list.

The New Hampshire Supreme Court issued case orders on Tuesday on two separate Laurie List appeals, and while the cases are similar, the different results highlight the fact the court is still defining how Laurie List functions since it became a public document in 2021.

The Laurie List, or EES, is a list maintained by the New Hampshire Attorney General’s Office of police officers with known credibility issues that need to be disclosed to defense attorneys. After the New Hampshire Center for Public Interest Journalism, publisher of InDepthNH.org, sued the state to make the list public, New Hampshire’s courts have been adapting to the new legal landscape.

Neither officer is named in the lawsuits decided Tuesday, but both share basic facts. Both officers were put on the EES after being accused of lying in incidents that took place more than a decade ago, and both officers had lower court judges rule the triggering incidents did not need to be disclosed during trials when considered as part of possible evidence.

But the key facts the Supreme Court seemed to base the decisions on is the weight of the evidence against the officers.

The first John Doe was accused of lying during an internal investigation in 2013, but the Supreme Court justices found his reported lie came down to a possible misunderstanding of an unclear question.

In 2013, the officer was told by a relative of his police chief that a complaint had been submitted over some incident. The same day, the officer was given a letter that an internal investigation was underway into the complaint, and he later spoke with the investigator. During that interview, the officer was asked how he learned about the investigation.

“[T]he plaintiff ‘verbally stumbled with a response’ and gestured to the department’s mail slots. He then said ‘from your . . . letter advising of the complaint,’” court records state.

The officer was never disciplined over the complaint, but instead the investigator determined that he lied about first hearing about the investigation from the letter and not from the chief’s relative. However, the officer claimed he learned about the complaint before he got the letter informing him about the investigation, and therefore he did not lie.

It was over this alleged lie that the officer was placed on the EES, and not over any complaint or other misconduct. The Supreme Court ruled that the potential confusion over the interviewer’s question creates enough doubt about whether or not the officer lied at all.

“The plaintiff claims that, although he told the investigating officer that he had spoken with another officer regarding the complaint, ‘he was honest in answering that he only became aware of the investigation when he was formally apprised of it in writing,’” the Supreme Court ruled. “We agree with the plaintiff that it is unclear whether the investigating officer asked him when he first learned of the complaint or when he first learned of the investigation.”

The case against a second John Doe, a New Hampshire State Trooper, is less ambiguous, according to the court. More than 14 years ago, the Trooper failed to appear at an Administrative License Suspension hearing. When he requested a rescheduled hearing, the trooper claimed he never got the first notification that was sent to his email account, and actually testified he never got the email during the rescheduled hearing.

Unfortunately for the trooper, a follow-up internal investigation found that not only did he get the original email notification, he reportedly deleted that email after he missed the first hearing. The trooper was disciplined and he appealed to the Personnel Appeals Board, which also found he lied during its hearing.

Even though he went on to have an exemplary career and the incident was more than a decade old, the lies about the email are enough to keep him on the EES, the Supreme Court ruled.

“In light of these undisputed facts, we conclude that while the misconduct occurred over ten years ago and, according to the trial court, the plaintiff ‘apparently had an exemplary career as a trooper’ since then, the misconduct is nevertheless potentially exculpatory impeachment evidence ‘that is reasonably capable of being material to guilt or to punishment,’” the justices wrote.

The fact that a lower court judge deemed the trooper’s email lies did not need to be disclosed during other proceedings does not mean the incident can’t be disclosed at some point, the Supreme Court ruled. Whether an EES issue is disclosed to a defendant in a criminal case depends on the facts of the criminal case and does not reflect an opinion about the EES status.

“That the circuit court concluded that disclosure of that information to the criminal defendants in two separate criminal proceedings was not required does not necessarily mean that the court concluded that the information was not ‘potentially exculpatory,’ and that plaintiff’s name should be removed from the EES,” the Supreme Court ruled.