By STEVE TAYLOR

It was almost five o’clock in the morning and the election was coming down to the vote totals from the three wards in the City of Claremont. Ballots were still counted by hand in those days, but out of 299 New Hampshire voting precincts the statewide tabulation was stalled for over an hour, waiting for just those three to be reported.

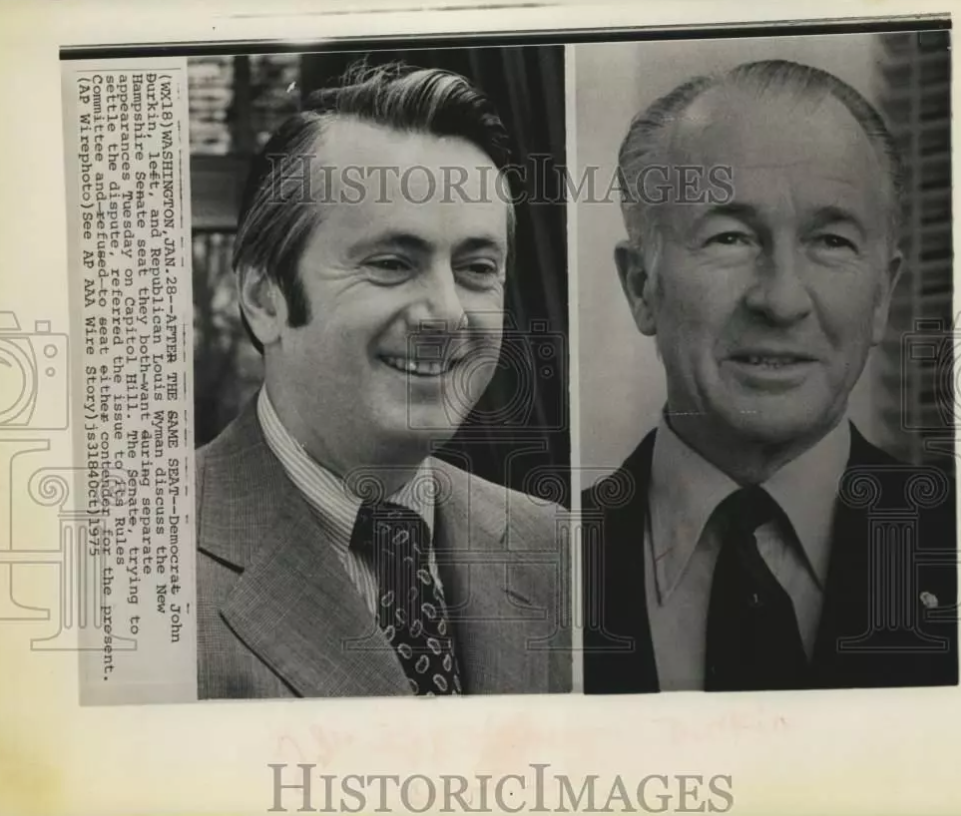

The stage was thus set for what would become—and still is—the closest race for a U.S. Senate seat in history. It was 50 years ago this week, Nov. 5, to be exact, that the result would come down to a margin of two votes; yes, two votes out of some 222,000 ballots cast.

Louis Wyman had led the race throughout the night, no surprise to the political cognoscenti, but it was a lot tighter than anybody had expected. The tabulation before those last three wards reported in had the Republican Wyman in front by 898 votes over Democrat John Durkin, enough to generate amazement among those who hadn’t long since gone to bed assuming Wyman would keep the seat safely Republican.

But at last Claremont City Clerk Rose Ellen Haugsrud had those ward tallies, and when they were blended into the statewide total, it came down to a two-vote (yes, two-vote) victory for Durkin. Claremont in 1974 was still a solid union place, and two wards voted for Democrats reliably for decades. This time, though, all three went Democratic for a citywide margin of 60 to 40 percent.

Thus began a drama that would run for more than 10 months. In a precursor to the 2000 Bush-Gore battle over disputed ballots, New Hampshire officials and politicians– and eventually partisans in the U.S. Senate–wrestled over a batch of ballots that one side or the other believed should be disallowed.

That two-vote edge generated by news organizations’ tabulations would stand for a few days until the official secretary of state’s canvass had Wyman up by 355 votes. Durkin demanded a recount, which concluded on Nov. 27 showing him the winner by a margin of 10 votes. Gov. Meldrim Thomson then gave him a provisional certificate of election.

Wyman immediately appealed to the state Ballot Law Commission, and legal maneuvering would continue in both state and federal courts for weeks. Durkin’s lawyers called for the U.S. District Court to ship the whole matter directly to U.S. Senate for arbitration, but a federal district court judge denied the request. Then the Ballot Law Commission did a partial recount, and on Christmas Eve announced that Wyman had won by two votes.

Thomson took back the certification of Durkin and gave Wyman a fresh credential. The retiring incumbent, Norris Cotton, resigned his seat four days ahead of the expiration of his term in order to give Wyman an edge in seniority rankings after Thomson had appointed him to serve the balance of Cotton’s term.

Undeterred, Durkin petitioned the U.S. Senate to look at the New Hampshire situation, citing a provision in the U.S. Constitution that claims that each house of Congress is the final arbiter of elections to its respective body. The Senate at the time was controlled by Democrats, who held a 60-vote majority. The Senate Rules Committee met Jan. 13, the day before Congress was to convene.

The committee consisted of five Democrats and three Republicans, but Alabama Democrat James Allen voted with the Republicans, claiming Wyman had presented proper credentials, resulting in a 4-4 deadlock. The matter was soon referred back to the Rules Committee, which established a special panel of staffers to examine 3,500 questionable ballots that had been shipped to Washington. This resulted in a report citing 35 points of contention, which triggered six weeks of debating the validity of the various ballots. Republicans mounted a successful filibuster that blocked the seating of Durkin.

The deadlock would roll on well into summer. On July 28 a Washington Post editorial chided the Senate for planning to head off on August vacation without settling the New Hampshire election mess. It called on Wyman and Durkin to seek an agreement themselves. The next day Wyman proposed a special election to try to end the stalemate, a proposal Durkin initially refused, but he then accepted on July 30. Durkin went on television back in New Hampshire announcing his willingness to have a fresh election to unsnarl the matter.

Next he reported his change of heart to Senate leaders and the body then voted 71-21 to declare the seat vacant as of Aug.8. Thomson appointed Cotton to hold the seat while preparations were underway for a special election. The rerun of the Wyman-Durkin race attracted national media attention and it revved up voter interest, such that on Election Day, Sept. 16, a record turnout cast ballots.

This time Durkin would win with 53 percent to Wyman’s 43 percent out of 253,785 ballots cast. It would be the last election in 33 years where a Democrat would claim a New Hampshire U.S. Senate seat.

Durkin’s impressive showing at the time was chalked up to voter dismay over revelations surrounding the Nixon Administration and the Watergate scandal. But Wyman lost ground when he had an angry meltdown the night of Nov. 5 when it became clear he hadn’t waltzed to easy victory. He chastised voters, particularly in Portsmouth, for not rewarding him sufficiently for work he believed he had accomplished in Washington during the years he served as the Congressman for the state’s southeastern district.

Wyman had made his name as the state attorney general for eight years during the height of the 1950s Red Scare period. He spearheaded investigations of suspected communists, sympathizers, so-called five percenters and fellow travelers believed to have been scattered around the state. His work meshed with that of the much-publicized U.S. House UnAmerican Activities Committee and was summarized in a book-length report to the legislature. When the heat of the chase subsided he moved on to a single term as Congressman before losing his seat in the 1964 Lyndon B. Johnson tidal wave. But he regained his perch in 1966 and went on to serve four more terms before raising his sights to the U.S. Senate.

He quit elective politics for good after losing the special election to Durkin, and in 1978 was appointed by Thomson to a seat on the Superior Court bench, where he served till 1987. In Congress, Wyman was a staunch conservative and once was quoted as saying there were “too many Negroes” in Washington, D.C. He invariably projected a patrician demeanor and didn’t suffer fools well.

Where Wyman often seemed abrupt and distant, Durkin reveled in a kind of tough guy, man- of- the-people attitude. During a contentious session of a recount he said he was ready to “fight all the way to the end of the bar and out into the street.” He had served a stint as state Insurance Commissioner, and battled regularly with major insurers over rates and policies. He had bipartisan support and, as his term was ending, “Keep Durkin Workin’” buttons began to sprout around the statehouse, When his term was up, he refused to leave his office, saying he still had important work left to complete, but Thomson sent state troopers to force him to depart.

Warren Rudman was nominated by President Gerald Ford to be chairman of the Interstate Commerce Commission. Rudman had compiled a solid record as state attorney general, but Senator Durkin chose to bottle up the nomination, effectively killing it. It would be Rudman who would end Durkin’s time in elective politics in 1980 when the Ronald Reagan-led Republican ticket swept hundreds of Democratic candidates away.

But Durkin could also be gracious. On election night 1980, when votes were still being tallied, Durkin telephoned Rudman at his campaign headquarters and told Rudman he had won, he Durkin had lost; Durkin said he’d resign early so Rudman would get an edge on Senate seniority.

Brad Cook, a onetime Rudman staffer and now a prominent Manchester attorney, offers some insight on how things went down after that 1980 election:

“Rudman went on to serve two terms with distinction and he and John Durkin, both now departed, became good friends and spent many hours recounting their past experiences, notwithstanding the tension between them and resentments over prior events.

“One interesting footnote is that Durkin might not have run against Wyman if Gov. Meldrim Thomson had not had him physically removed from the Insurance Department when his term was up as commissioner, and Rudman might not have run if Durkin had not blocked his nomination to the ICC by President Ford,” Cook wrote in a 2014 monograph.

Steve Taylor resides in Meriden and contributes occasionally to the Valley News. For many years, including 1974-75, he managed New Hampshire election tabulation operations for the News Election Service, a national pool of wire services and broadcast networks. He also serves on the New Hampshire Center for Public Interest Journalism’ board of directors.

.