Recently released federal data indicate that county, city, and town governments in New Hampshire likely have millions of flexible, unspent federal dollars that must be committed to a purpose before the end of the year. While the majority of the funds have already been spent or are otherwise obligated to be spent, counties will need to have taken some additional action before December 31, 2024 on the approximately $52.3 million that were, as of the end of March, at some risk of recoupment by the federal government. Information from cities and towns suggested about $31 million in obligated funds remained at the end of March, although data were incomplete.

Flexible Federal Funds and a New Year’s Eve Deadline

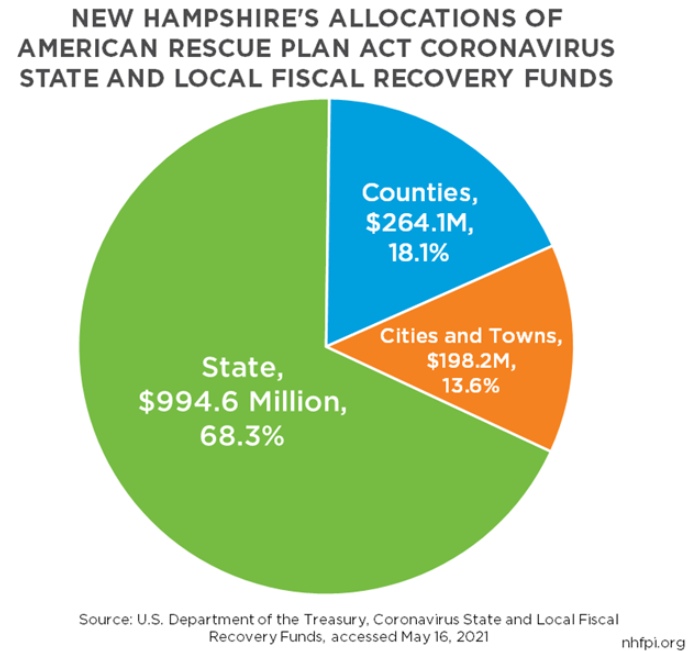

The federal American Rescue Plan Act, enacted in March 2021, provided one-time, flexible funds to the State government and to counties, cities, and towns. This rare opportunity resulted in about $1.457 billion in relatively flexible funds made available in 2021 and 2022.

The funds, called the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (CSLFRF), can be used for a remarkably wide array of purposes relative to most forms of federal aid to state and local governments, which typically have substantial and specific requirements directing their uses. Permissible uses have been added over time, including a July 2024 expansion of allowed uses for affordable housing investments. Eligible uses for these funds include:

- replacing public revenue lost due to the COVID-19 pandemic;

- responding to the adverse public health and economic impacts of the pandemic;

- providing premium pay, including retroactive pay, for essential workers;

- investing in necessary water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure;

- supporting certain types of transportation projects and community development initiatives; and

- providing relief for natural disasters.

When these funds were first provided, the federal government encouraged state and local governments to “consider funding uses that foster a strong, inclusive, and equitable recovery, especially uses with long-term benefits for health and economic outcomes.” The federal government also stated that “these resources lay the foundation for a strong, equitable economic recovery, not only by providing immediate economic stabilization for households and businesses, but also by addressing the systemic public health and economic challenges that may have contributed to more severe impacts of the pandemic among low-income communities and people of color.”

The CSLFRF dollars must be spent by December 31, 2026; any funds unspent after that date will be returned to the federal government. More critically for policymakers this year, the CSLFRF must be obligated by December 31, 2024. Obligation, as defined by the federal government for this purpose, “means an order placed for property and services and entering into contracts, subawards, and similar transactions that require payment.” Obligation can also include certain salaries and wages to be paid to public employees, interagency agreements structured similarly to a contract or subaward, compliance costs associated with administering the CSLFRF, and instances of certain reclassifications of projects after the December 2024 deadline.

Budgeting the funds for a particular purpose through a policymaking body’s approval would likely not be sufficient to be considered obligated by the federal government. Unbudgeted funds and funds that are budgeted but unobligated will need some relevant policy action taken this calendar year to avoid recoupment.

Four Counties Reported Significant Unobligated Funds

The American Rescue Plan Act’s distribution formula for counties was based on each county’s share of the U.S. population. As a result, no adjustments were made for differing responsibilities of county governments within different states, or between counties based on budget sizes or policy initiatives.

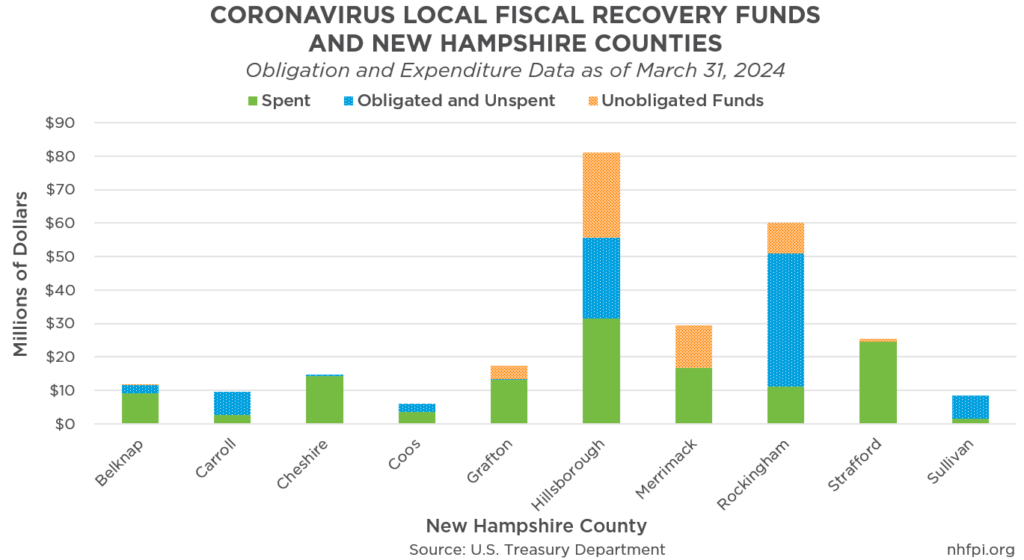

Counties in New Hampshire received a total of $264.1 million in Coronavirus Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (CLFRF) during 2021 and 2022. By the end of March 2024, counties reported spending $128.3 million (49 percent) of these funds, and obligating $211.8 million (80 percent) of the total funds received across the ten counties. A total of $52.3 million (20 percent), or one in every five dollars made available to counties, had not yet been obligated nine months before the deadline.

However, these unobligated funds were not evenly distributed across counties. Carroll, Cheshire, Coos, and Sullivan Counties all reported having obligated all of their funds by the end of March 2024, while Belknap and Strafford Counties reported less than four percent of their original funds were unobligated at the end of March.

The remaining four counties reported significant remaining unobligated funds. Grafton County had $4.1 million (23 percent) unobligated, and Rockingham County had $9.1 million (15 percent) remaining unobligated. The county with the most unobligated funds remaining was Hillsborough County, with $25.3 million (31 percent), or nearly half of the county-level total. Merrimack County had the largest portion of its original funds unobligated, with $12.7 million (43 percent).

Data for Municipalities Incomplete, May Not Fully Reflect Status

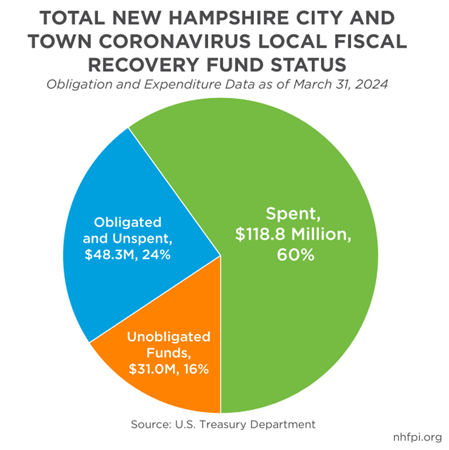

Municipalities in New Hampshire have been spending these flexible funds at a faster rate than either counties or the State government, but incomplete data and concerns about whether funds reported as obligated truly meet the federal definition may be cause for concern.

In total, New Hampshire cities and towns reported spending $118.8 million (60 percent) of the original $198.2 million in CLFRF appropriated to them by March 2024. Another $48.3 million (24 percent) were reported as obligated but not yet spent, for a total of $167.2 million (84 percent) of funds that were likely not at risk of recoupment. About $31.0 million (16 percent) of the total required some action to obligate or spend these funds in the final nine months before the deadline to avoid recoupment.

However, this analysis of remaining available funds is made less certain by some complications with these data. First, 38 of New Hampshire’s 234 recipient municipalities did not have data available in the published federal dataset. Of those 38 communities, 11 were identified as having received funds in the federal data, while the remaining 27 also did not appear in the federal list of recipient communities, although recipient funding amounts were initially estimated by the State. Municipalities may be absent from the dataset because they missed reporting deadlines or may have encountered technical challenges when interacting with the federal data portal, which was a challenge identified by some communities in New Hampshire. These missing data suggest that obligations and expenditures may actually be higher than the available data suggest.

Second, some of these reported data may be based on an inaccurate understanding of obligation. Instances documented elsewhere in the country suggest local governments may have budgeted funds to a specific purpose and considered them obligated; however, without a binding agreement to spend the dollars, the federal government would likely not consider those funds obligated, putting them at risk of recoupment after the end of December 2024. Project-based data reported by municipalities, which is available on the U.S Treasury Department’s website, shows some potential examples of this in New Hampshire communities. One New Hampshire town reported budgeting and obligating, but not yet having spent, $100,000 to purchase a new fire truck; if there is not a binding agreement, such as a contract, that the town has entered to purchase a fire truck, then the federal government may not consider those dollars obligated. Another town reported obligating $50,000 to renovate the local food pantry, including removing old kitchen appliances, upgrading the electrical work, installing a new ceiling, and adding a new door, shelving, and air conditioning, and having spent $16,239 on that project as of the end of March. Unless those renovation projects are all reflected in agreements that “require payment” for the full $50,000, then those funds may only be budgeted, and not obligated, under federal rules. While these data suggest municipalities have obligated about $48.3 million, the total may actually be lower if local governments are reporting these funds as obligated when they are only budgeted, based on federal rules. Crucially, such a misunderstanding would also mean some cities and towns may be at risk of losing funds, due to noncompliance, despite having planned a purpose for their use.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/1y3uX/5

Third, municipalities have reported obligating and spending these funds at substantially different rates. Based on the available federal data, 113 cities and towns reported obligating or spending at least 95 percent of their CLFRF allocation. However, 13 reported obligating or spending less than 25 percent of their CLFRF as of the end of March 2024, and five towns (Alexandria, Lancaster, Lincoln, Orford, and Walpole) had not obligated any of their funds, according to the published federal data.

Looming Risk of Losing Funds

The federal government does not typically provide State and local governments with funds that have as few restrictions, and broad uses, as came with the CSLFRF. Policymakers at the State level have begun the reallocation process to help ensure that no funds are recouped. Counties, cities, and towns may seek to clarify whether the legal structures supporting their obligations of funds are sufficient to avoid the risk of recoupment by the federal government after New Year’s Eve. For governments with unobligated funds remaining, the federal government has published rules and guidance that indicates eligible uses of these funds, and examples of ways jurisdictions around the country have used them to support an equitable and inclusive economy, including affordable housing and supports for the workforce and small businesses. Counties, cities, and towns may wish to assess the status of their own flexible federal funds and seek community input to creatively and effectively deploy funds to support the well-being of their residents.

– Phil Sletten, Research Director