By GARRY RAYNO, InDepthNH.org

CONCORD — A workforce that has not rebounded to pre-pandemic levels is the biggest constraint on New Hampshire’s economic growth according to a brief from the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute.

Released before the Labor Day Weekend, Phil Sletten, the institute’s research director, says the two biggest issues negatively impacting workforce participation are housing and child care costs and accessibility.

The study notes the number of people out of the workforce due to child care is likely larger than the total number of unemployed people who are actively looking for work.

The brief suggests greater investment in housing and child care as the latest state budget provides, but needs to continue in order to attract more workers to the state.

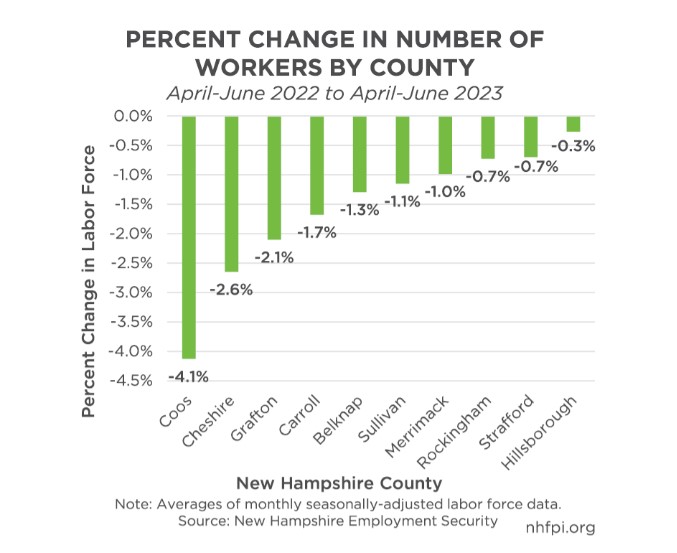

The brief also notes the number of people in the workforce is declining from a year ago compared to the second quarter of each year, and the decline is most prominent in the state’s rural counties while the four southeastern counties — Rockingham, Strafford, Hillsborough and Merrimack — have seen the least decline.

Sletten cautions the state’s demographics are impacting the workforce with its aging population growing and retiring.

The number of people between the ages of 65 to 74 years old is expected to grow to 200,000 individuals in the next 10 years, he notes, which is a substantial number of people in a state with a population of 1.4 million.

He said with unemployment at a record low, and the state’s workforce facing demographic headwinds, investments in child care and housing are easier to address than the aging workforce, and makes investments in housing and child care essential for economic growth.

“While a significant portion of New Hampshire’s workforce constraint is likely due to residents who have reached a traditional retirement age leaving the labor force, the lack of access and affordability of both child care and housing are key constraints that can be more readily addressed by policy, such as some of the initiatives in the recently-enacted State Budget,” Sletten writes. “However, these constraints are significant, and will likely remain without further significant investment.”

Both areas received substantial federal resources in pandemic relief and recovery programs that are now winding down.

Sletten noted child care is a service industry and could see a quicker impact from public investment, while housing, which has great demand, is capital intensive and will take longer to address, noting it has been a growing problem in the state for a decade-and-a-half.

Compounding the problem is the high cost of higher education in New Hampshire.

Sletten said 56 percent of the graduating students seeking a four-year degree leave New Hampshire for their education, which is the second highest percentage in the country, with only Vermont higher.

New Hampshire has the second highest tuition costs for a four-year institution in the country, with only Vermont higher, and the third highest costs for a two-year college, behind South Dakota and Vermont.

Sletten said in per capita funding for higher education, New Hampshire is substantially lower than any other state at $106 per person, the second lowest is Pennsylvania at $142 per person, while the national average is $318 per person.

New Hampshire is about one-third of what support is nationwide, Sletten noted.

The economic rebound after the first year of the pandemic was faster for New Hampshire than the other New England states, but then its growth leveled off while the other state’s continued to grow.

“New Hampshire’s growth was likely slowed by workforce limitations,” Sletten writes. “Between the second quarters of 2022 and 2023, the number of residents reporting that they were employed declined by about 740 people (0.1 percent).”

Yet employers reported greater job openings, which may reflect cross border commuting for work, according to the brief.

Per capita personal income grew faster in New Hampshire between 2015 and 2019 than the other New England states, but since the pandemic recession, Massachusetts and Maine have nearly caught up with New Hampshire.

The professional, science and technology sector in New Hampshire has seen the greatest income growth and has more jobs now than before the pandemic as do the administrative and support services and waste management, wholesale trade, and mining, logging, and construction sectors.

Jobs in the retail trade sector, which includes in-person storefront staff, have fewer jobs than before the pandemic, and that is also true for government, the arts, entertainment, and recreation industries.

Retail trade is the second-largest employment sector in the New Hampshire economy, according to the brief, while health care and social assistance is the largest industry.

The accommodation and food service industry also has fewer jobs than before the pandemic began, but had the highest percentage of increase in wages since 2019, which was not enough to bring employment levels to pre-pandemic numbers.

The average wage in New Hampshire has fallen behind inflation relative to the most recent data from 2021, according to the brief.

“With a third of Granite State adults surveyed reporting that paying for usual household expenses is somewhat or very difficult, economic growth may be more likely to remain slow despite the favorable national environment,” Sletten writes. “Providing targeted supports and making investments to expand opportunities for households to access key needs, including child care and housing, has the potential to substantially help New Hampshire’s residents and economy thrive.”

Sletten noted there are more jobs available per person seeking work, then there were prior to the pandemic recession.

In February 2020, there were 1.9 jobs for each person seeking work, while in June of this year the figure was 3.3 jobs for each unemployed person seeking work and peaked in March at 3.7, Sletten said.

Across all industries the worker shortage is more severe than it was prior to the pandemic and prior to the great recession, he said.

Garry Rayno may be reached at garry.rayno@yahoo.com.