The Extraordinary Life and Mysterious Disappearance of Thomas Thor Tangvald

By BEVERLY STODDART, A NH Writer’s Life

Part 1 – Peter Tangvald

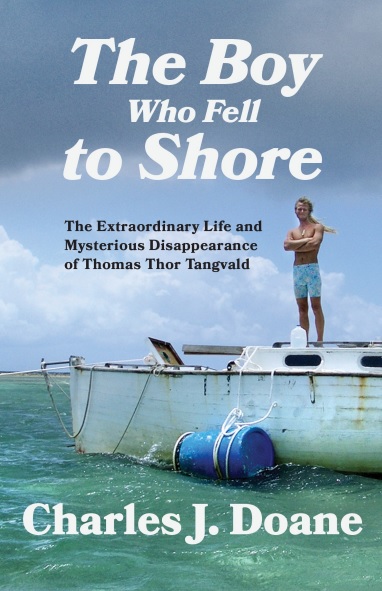

PORTSMOUTH, NH: In Charles Doane’s book, The Boy Who Fell to Shore: The Extraordinary Life and Mysterious Disappearance of Thomas Thor Tangvald, Latah Books, he explores the life and circumstances of Thomas Tangvald, son of famed bluewater sailor Peter Tangvald. Theirs is a life unlike most, lived on the sea in wooden boats without electricity or any means of communication.

Doane is an author living in Portsmouth.

To know Thomas, we first explore his father, Peter.

Peter lived by his own rules. He married seven times, beating Henry the Eighth by one. Yet, they both had two wives that died. One of Peter’s wives was killed by a bullet from pirates who were overtaking their boat. The other died when the sail boom swung unexpectedly and knocked her off the boat, never to be seen again.

Thomas was born on the boat and was raised there with his younger sister. Often they were kept in a jail cell made especially for them, which was tiny and locked from the outside, presumably to keep them safe and away from their father, who was single-handedly sailing the boat.

Whether you like books about sailing or not, this is a fascinating read that has as much intrigue, animal attraction, and adventure that I could not put it down. You have to read it to believe what Peter, did to get seven women to board the boat, sail the seas, work in drudgery, and bear his children.

Would you explain what a bluewater sailor is?

“Bluewater refers to the open ocean. A bluewater sailor can be anyone who routinely sails on the ocean or in open water in any capacity. [Examples include,] a racing sailor, or a professional who does deliveries, also cruisers who live aboard and move around usually with the seasons, from place to place living on their boat.”

What got you interested in bluewater sailing?

“I got interested in sailing from reading. One book that set me off was Song of the Sirens by Ernest K. Gann, who had an amazing life. [He], among many other things, was interested in sailing and Song of the Sirens is a memoir about the boats he’s owned in his life. The primary subject is this huge schooner he bought in Holland in the 1950s called Albatross. He was a very good writer, very evocative and that book just got me. It was ocean sailing; specifically, that captured my imagination. I taught myself to sail small boats on the coast of Maine. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that I finally said to myself, if you’re ever going to sail across an ocean, you have to get around to it now. I was in my early 30s.”

How many people are in this community of bluewater sailing?

“It’s hard to say. In a footnote in the book, I mention that the most popular and heavily trafficked route for recreational bluewater cruisers is from Europe to the Caribbean in the fall and winter. The major jump is from Las Palmas, the Canary Islands, to the West Indies. There’s an organized rally that runs. It always sells out. It’s got like 230 boats in it. Somebody did a survey of major routes and found that that was the heaviest route, with more than a thousand boats each year. Between two to six people on each boat, some are single-handed, but they’re the minority. Couples sailing together is the most common thing. Couples with young children are not unusual and groups of friends. When they’re doing a big jump across the Atlantic, often a couple will get some sailing friends to come along to augment the crew.”

They’re sailing, not motoring?

“The question you always get from people when you tell someone you sail across the Atlantic Ocean, the first question is where did you stop at night? You don’t stop at night. You’re running 24/7; ideally, somebody is awake all the time standing watch. What most boats do is set a fixed watch rotation. Depending on the crew size, you are on four hours at a time. You’re in charge of keeping an eye on things, making small adjustments if necessary, getting people up if something big has to be done.”

“Increasingly, for some people, it’s a bucket list item. Around the time I got interested in bluewater sailing, what changed the game was in the first gulf war, GPS satellite navigation units became affordable. When I first started, a GPS unit cost over $1,000. This isn’t like electronic charting you see today; it’s giving you a readout of your latitude and longitude. That’s all you were getting, but that was huge to continuously know where you were. During the first gulf war, the military decided they wanted everybody on the ground in Iraq to have a GPS in their pocket. The companies producing these things suddenly had a lot of orders, and it dropped the price to get one to below $200. After that, everyone had a GPS unit on their boat. Once you have that, you didn’t have to learn celestial navigation, which is a huge barrier. It opened it up for people who didn’t want to get into spherical trigonometry or learn how to use reduction tables. From that point forward, it was easier for people to do it on a more casual bucket list basis. The community got much larger as a result.”

I loved the book.

“I’m hoping people who don’t know anything about sailing can get into this book.”

I can tell you it infuriated me as a reader, but still, I loved it. It’s a great, well-written story and more than just a sea voyage. Let’s start with Peter. Steve Macek, an “old friend” of “the famous Marco Polo schooner, Star,” said, “Peter was a Nazi.“

“When I met Steve Macek, he was on his boat, I was on my boat in Bermuda, and I’d seen his boat around the Caribbean several times; it’s a unique boat. I found out how long he’d been sailing, and I said, I bet you know the Tangvalds. He said yes, “Peter Tangvald, he was a Nazi.”

To get a better understanding of who Peter was, the list of wives and their descriptions follows.

1 – Reidun Kathle. His first wife was Reidun. They were childhood sweethearts, got married and she emigrated with him to the United States in the late 1940s and left him in California and they had three children. He continued on with his life. Edward Allcard had known Tangvald for 34 years. They first met in 1957, and Edward became Thomas’s foster father in 1991. It wasn’t until then that Edward discovered that Peter had had three children before. He never mentioned them. He basically abdicated them.

2 – Helene. There is no last name available for Helene. He met her in California, and she left him after a business he ran had gone bankrupt.

3 – Lillemor Thorkildsen. Lillemor could not stand a life at sea and gave Peter an ultimatum, her on land or him at sea without her. He chose the sea.

4. Simonne Orgias. A French schoolteacher, they met in Martinique, and he convinced her to leave her job and sail with him. They married and stayed together until…

5 – Lydia Balta, …he met seventeen-year-old Lydia Balta. When Simonne caught them in bed, Lydia became the next wife. She was Thomas’s mother, Peter’s fourth child, and he was born onboard the boat. Lydia was so torn up from the birth, Peter mended her with glue. Lydia was shot and killed by pirates south of the Philippines in the Sulu Sea.

6 – Ann Ho Sau Chew. Peter and Ann were together for five years. He met her at a school in which Thomas was enrolled. She was Carmen’s mother and Peter’s fifth child. Ann was killed while doing laundry when a boom moved from one side of the boat to the other knocking her into the water. Her body was never found.

7 – Florence Mertens. They met when she was eighteen and he was sixty. She was the mother of Virginia, Peter’s sixth child. After years of struggle and starvation with Peter and the three children, she had enough. She left him, taking Virginia with her and leaving Carmen and Thomas with Peter.

What was it that Peter had that he could attract seven women to serve him on the boat.”

“It does seem improbable that someone would be that attractive. He’s a very handsome man. I never met him. I read his book. I didn’t know who Peter Tangvald was until shortly after he died. I was inhaling ocean sailing literature. In high school, I had sailing magazines stacked up the way most boys would have Playboy and Penthouse under their beds. I didn’t start reading a ton about ocean sailing until after I did that on Constellation. I came back and said I’m doing this on a boat of my own, and I was reading everything I could get my hands on. This would have been in 1995, Peter died in 1991, and his book came out within a year in English; I found it and read it a couple of times. It’s an amazing story. And I find out eventually it’s not all entirely the way it happened. Then I read his first book. There’s a famous cruiser, Lin Pardey, who met the Tangvald in the Philippines and was inspired by his first book, which is about sailing around the world in a small boat without an engine. Lin and her husband, Larry, were both inspired by that book, sailed around the world a couple of times, and became very influential in the bluewater sailing world in the 1970s and 1980s. [They sailed] on a small boat they built without an engine and cited Peter as their inspiration for going without an engine. After Larry died and Lin retired and started publishing sailing books, she wanted to republish the first book Sea Gypsy, got a hold of an old copy and read it, and said I can’t publish this. It was too sexist. This is back in the 1960s. You could write about these things and not suffer for it, about his relationship with his third wife, Lillemor, and how dismissive he was of her. And the sex tour he got into chartering in the Caribbean. He met these guys on a beach who wanted to get laid, and he said I’ll take you to St. Lucia and took them on a sex tour of St. Lucia, which he describes in detail in the book.”

“There wasn’t a wire on the boat,” I love that line.

“That’s from Steve Macek, and he was cited as a source. Steve Macek was an electrician before he took off and went sailing. He knows electricity. So when he says there wasn’t a wire on that boat, he means there was no electrical current on the boat at all.”

Primitive.

“That’s how the Pardey’s sailed, for example. You don’t need electricity on a boat. Lin and Larry used oil lamps and hand pumps. It can be done. I’m sure they had a hand-held radio.”

Peter had nothing.

“No radios. Maybe a flashlight. He sets out with his son, Thomas, and Carmen, who is just seven years old. He does this without any thought whatsoever. I was amazed that one would take a young teenager and a seven-year-old girl out on a boat without caution.”

“He was reckless all through his life on what a bluewater sailor would call weather routing. If you’re living on a boat and sailing across any large body of water, I always like to say the weather is your life. It’s the only thing that matters.”

It’s not pirates.

“Weather is the most important factor, always. He used to take chances with the weather. Even when he was old and infirm and starting to feel where he couldn’t confidently sail that boat himself anymore, he took off.”

He’s got a tiny seven-year-old girl with him. Would you explain where he kept those children and what he did to those children?

“As I mentioned in the book, he was sailing with children from the 1970s. And, the forepeak, the forwardmost cabin on the boat, he turned the forepeak into a jail cell for children. It had a lock on the door, grate overhead on the deck hatch so they couldn’t get out through it – for safekeeping. A simple utilitarian answer to the problem is how you mind a child sailing on a boat. I can’t say exactly when he fortified the forepeak. The first woman he sailed with children was his teenage bride, Lydia Balta. Thomas was born on the boat.”

Lydia Balta was Thomas’s mother.

“He sailed with Lydia and Thomas on the boat from Singapore, Southeast Asia, Taiwan, and the Philippines before Lydia was killed. It would be interesting to know whether or not the forepeak was set up as a jail cell at that time or if it came later. My assumption would be he started that after Lydia was killed and he had to sail with Thomas. How will I handle this two or three-year-old kid and sail a boat single-handedly? Facing the problem in that context is not an insane thing to do. If you’re single-handed with a kid on board, sometimes you are focused on the boat. You can’t keep an eye on the kid. Most people put their kids in harnesses. You always have to be clipped onto something on the boat. He never had his children in harnesses. He wouldn’t let them on deck until they reached a certain age. Then when he couldn’t mind them personally, he locked them up.”

What were Peter’s consequences for the loss of Lydia?

“[When he showed up in Brunei without his wife on board, Lydia, who had from the authorities point of view, disappeared.] And the story was they’d been boarded by pirates, and she’d been shot. They didn’t believe him. He was held in Brunei for some time on suspicion of murder. In the end, they did a photographic recreation of the robbery, the act of piracy. Peter, when Lydia was shot, had been standing at the tiller of the boat in the cockpit and Thomas was clinging to his leg. So they took a photograph of that, and the story police told him when they finally were free to go, was we looked at this photograph and said we always wondered why the pirate didn’t kill you. If you’re a pirate and you board a boat and you kill one person, you don’t want to leave witnesses, you kill them all. That question in our mind is why didn’t they kill you? We looked at that photograph and said they didn’t have the heart to do it with that boy looking at them.”

Soft-hearted pirates. Lucky for him he didn’t get killed.

They are pirates in the sense they would be impoverished fishermen. Peter’s description when they left they seemed eager to get away as he was.

To end with Peter, would you explain what happens to Peter, Carmen, and Thomas, which brings in Edward and Clare Allcard?

“The book starts by telling the tale of how Peter and Carmen died and how Thomas became an orphan. By this time in Peter’s life, he wasn’t firing on all cylinders. He’s in his mid-sixties and had a couple of heart attacks. He has angina. There was within the year before setting out on this voyage. A man named Gary “Fatty” Goodlander met him in St. Johns and found he couldn’t raise the mainsail on his boat. He had to get help from other cruisers to get help out of the harbor. I think he changed the rig to make it easier for him to sail on his own.”

“Thomas had moved off the boat. By this time, he was fifteen years old, had been born and raised on his father’s boat his entire life, and was looking to put a little distance between himself and his dad. [To] assert a little independence, all he could think to do was get a boat to live on. He bought a little wrecked boat for $200 and worked at fixing it up. His father wanted to take the whole family from Puerto Rico down to Bonaire to escape the summer hurricane season. They were on the island of Culebra, just off the east coast of Puerto Rico, and wanted to get out of the hurricane zone. Bonaire is far enough south, just off the coast of South America. Hurricanes don’t go there. It’s 400 miles, and Peter wanted to tow Thomas and his boat 400 miles across the open Caribbean to Bonaire. With 300 feet of line, Thomas needed to be aboard his boat to bail it out. It’s got a huge cockpit relative to the length of the boat, so water splashes aboard. It’s a rough passage. You’re cutting across the easterly trade winds, which are quite strong sometimes. Thomas is just aboard bailing while Peter is sailing his boat single-handed with his seven-year-old daughter to mind.”

“After four days at sea, Thomas woke up at night just in time as it turned out to see that they were on the east coast of Bonaire. The windward side is open to all the waves marching across the Caribbean Atlantic Ocean. He was awake when he saw his father’s boat sail into the shore. It’s an ugly piece of shore, a sharp coral shelf. And he was able to jump overboard with his surfboard just in time before his boat followed his father’s onto the coral shore. Both boats were grounded to splinters.”

Was Carmen in the jail cell?

“Thomas recalls hearing his sister screaming inside the boat as he’s on his surfboard offshore. He’s got to hear this over what’s got to be a lot of surf. She most likely and most certainly was in the forepeak, locked up, and wouldn’t have been able to get out.”

In the next part, we will explore Thomas’s life.

Beverly Stoddart is a writer, author, and speaker. After 42 years of working at newspapers, she retired to write books and a blog. She is on the Board of Trustees of the New Hampshire Writers’ Project and is a member of the Winning Speakers Toastmasters group in Windham and the Ohio Writers’ Association. Her latest book is Stories from the Rolodex, mini-memoirs of journalists from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. A prized accomplishment was winning Carl Kassel’s voice for her voice mail when she won the National Public Radio game, Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me! She has been married for 45 years to her husband, Michael, and has one son and two rescue dogs.