Nancy West Photo

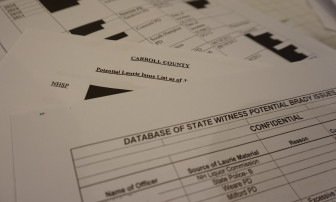

All 10 New Hampshire county attorneys keep a list of potentially dishonest police officers called “Laurie” lists.

The chairman of the commission formed to protect the rights of police officers placed on secret “Laurie” lists has filed confidential legislation that already has the backing of the Attorney General’s Office.

State Sen. Sharon Carson, R-Londonderry, chairman of the Commission on the Use of Police Personnel Files, submitted the proposed language “confidentially” that would provide potentially dishonest police with an appeals process before being placed on the lists.

The proposed legislation also prohibits firing police simply because their names are on “Laurie” lists, but would allow termination for the underlying behavior that prompted the designation.

It also would allow prosecutors to review confidential police personnel files seeking evidence of dishonesty.

“This legislation will be supported by our office with some minor tweaks,” said Senior Assistant Attorney General Susan Morrell, a commission member.

Carson said she files most of her legislation as confidential until the language is finalized, which is allowed under Senate rules. The practice is not allowed by House members.

Carson said she expects this piece of legislation to become public on Dec. 1.

“This isn’t set in stone,” said Carson, who also serves as the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The public will have ample opportunity to offer input after legislative services is finished with the appropriate language and she signs off on the bill, Carson said.

“Everyone will have the opportunity to weigh in,” Carson said.

Rep. Frank Heffron, D-Exeter, a member of the commission, said in an email that he didn’t receive a copy of the proposed legislation.

Heffron was also surprised to learn that state senators can file legislation confidentially until the bill is in its final form.

“I definitely was unaware that senators can file bills confidentially,” Heffron said.

Morrell said her office expects to soon finish updating the Heed memo, which has been used for a decade as the official guide in how police and prosecutors track and disclose testifying officers who have potential credibility issues.

The memo was written by then-Attorney General Peter Heed in 2004 to standardize the way police and prosecutors handle disclosing exculpatory evidence that is buried in confidential police personnel files.

Morrell expects the commission to continue its work for another year to review the updated Heed memo and other unfinished business regarding Laurie lists and the public’s right to know about the process.

InDepthNH.org obtained the proposed legislation through a request for the minutes of the last two commission meetings.

Steve Arnold, New Hampshire state director for the New England Police Benevolent Association, said accessing an entire police file for one issue involving discipline is not appropriate. He testified before the commission.

“Representing police officers in New Hampshire, we are adamantly opposed to any access to police personnel files except for the single incident that lands an officer on the Laurie list,” Arnold said.

Stephanie Hausman, deputy chief appellate defender for the state public defender’s office, said the commission was provided with a draft of legislation during its final meeting.

“I thought the draft addressed some important issues, but there was much discussion and editing during the meeting. I don’t feel that the commission members reached an agreement about the language before we adjourned,” Hausman said.

“My hope is that the commission is continued so that we can continue the discussion and reach a consensus on what legislation to recommend,” she said.

The commission was formed after police complained their due process rights were violated by being placed on Laurie lists, which could damage or even destroy their careers because it could limit their ability to testify.

The Laurie designation stems from the 1995 New Hampshire Supreme Court case State V. Laurie in which Carl Laurie’s murder conviction was overturned because prosecutors withheld the fact that the key police detective who testified against him was a documented liar.

Prosecutors are required to keep lists of police officers for possible disclosure to the defense when that officer is scheduled to testify.

Prosecutors are also constitutionally obligated to turn over to the defense all material favorable information, including police discipline that involves credibility problems for possible use impeaching the officer’s testimony.

Prosecutors are likely to lose convictions even decades later if it is discovered a police officer had been disciplined for lying and it wasn’t disclosed to the defense.

A convicted murderer in Nashua, Eduardo Lopez, is awaiting a judge’s ruling on whether he should get a hearing that could lead to a new trial because of an undisclosed lie told decades ago by then-Nashua Police Detective John Seusing, who testified against him.

Concord Attorney Jim Moir, an expert in Laurie matters who also testified before the commission, said the proposed legislation doesn’t require a police chief to notify prosecutors of potential Laurie issues, and doesn’t address Laurie lists.

Some commission members would like to do away with Laurie lists altogether.

Other issues, including the extent of the public’s right to know about dishonest police, are expected to be examined in the next legislative session if the commission continues its work as expected.

“Why do they need intermediate legislation?” Moir asked. “Why do it piecemeal?”

Moir said the commission agrees there are substantial problems when it comes to Laurie police issues.

“The whole process is mysterious. That’s the language they use. They want to demystify the process,” Moir said.

The proposed legislation does address what police officers can do to be sure they can challenge being placed on the list.

“Does the prosecutor not disclose this until the (police) appeals are done?” Moir asked.

“A prosecutor would be well-advised to simply disclose Laurie issues. If the officer is exonerated later on, so be it,” Moir said.

Otherwise it would pit the constitutional right of the defendant against the statutory right of the police officer, Moir said.

“The constitutional right trumps every time,” Moir said. “The commission has realized this is far more complicated than they realized going into it.”