By NANCY WEST, InDepthNH.org

A law professor filed a motion to unseal records of a fired Lisbon police officer who sued the town in federal court challenging his placement on the New Hampshire Laurie List of dishonest cops.

UCLA Law Professor Eugene Volokh’s filing in U.S. District Court in Concord also opposes the court continuing to keep the former officer’s name confidential.

According to Volokh, the officer was fired, would like to work as a police officer again and Volokh would like to write about the case, but can’t because of the sealing of records and John Doe designation.

“As American courts have long recognized, our judicial system is supposed to be open to the public, so the public (and the media, which serve the public) can see and evaluate what courts are doing,” Volokh said in an email.

“Sealing and pseudonymity interfere with that supervision. And while they are allowed in some cases (e.g., ones involving minors), that’s a rare exception to the rule of openness.”

While the filing involves only one former Lisbon police officer’s case, the federal court’s ultimate decision could impact whether the state Superior Courts can keep the lawsuits filed by officers on the Laurie List completely sealed under a John Doe or Jane Doe pseudonym.

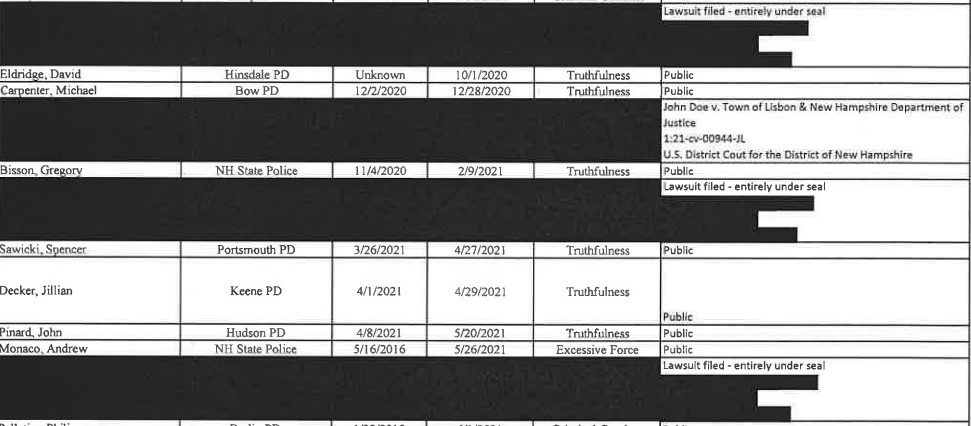

There have been 72 such lawsuits filed in Superior Court in the last six months by people on the Laurie List seeking to be removed. They have continued confidentiality in the meantime under the new law that is supposed to make public the names on the Laurie List, which is now called the Exculpatory Evidence Schedule.

The new law RSA 105:13d went into effect Sept. 24, 2021. It was a compromise by ACLU-NH and five news outlets, which have since withdrawn from the public records lawsuit, and then-Attorney General Gordon MacDonald. The New Hampshire Center for Public Interest Journalism is the only plaintiff left in the ongoing lawsuit.

According to the April 1 quarterly compliance report filed by Attorney General John Formella, 72 officers have notified his office that they have filed lawsuits under the new law. The officers’ names will remain redacted until their cases are decided by a Superior Court judge.

The new law doesn’t specifically require redaction in Superior Court filings, but does say: “Nothing herein shall preclude the court from taking any necessary steps to protect the anonymity of the officer before entry of a final order.”

Formella indicated it was the court that is filing the cases using pseudonyms John Doe or Jane Doe. The lawsuits do not show up in the portals that the public and press use to look up cases.

“We continue to seek clarification from the superior courts regarding the sealing of these cases and will release additional case-related information as permitted by the courts,” Formella said in the compliance report.

Last September, Formella’s office sent out letters to 254 of the 265 people whose names were on the Laurie List at that time notifying them they could file in Superior Court to have a judge decide whether their name should be removed under the new law.

That doesn’t include the 30 names that have been removed from the list by the attorney general through a confidential process since 2018, half since the new law went into effect in September.

Formella said the names of 174 names have been made public. There has been no action on the part of the attorney general or county attorneys to notify people who were convicted after testimony by police with undisclosed discipline for dishonesty, excessive force or mental instability.

The most recent Laurie list and compliance report can be reader here.

The U.S. Supreme Court case Brady v. Maryland and other cases over the years require all exculpatory evidence, or evidence favorable to a defendant, be turned over before trial. If such evidence is withheld, even years later, the defendant could seek a new trial.

Volokh said the right of access to the courts is protected both by the common law and the First Amendment, citing rulings from other cases.

“Only the most compelling reasons can justify the non-disclosure of judicial records,” Volokh wrote. “The mere fact that judicial records may reveal potentially embarrassing information is not in itself sufficient reason to block public access.”

Public access to judicial records and documents allows citizens to monitor the functioning of the courts, insuring quality, honesty and respect for our legal system, he wrote.

Police Officers

There is a particular public interest in lawsuits brought by police officers, and lawsuits brought against governments, he said, because they are public officials who wield immense power and enforcement discretion.

“The appropriateness of making court files accessible is accentuated in cases where the government is a party: in such circumstances, the public’s right to know what the executive branch is about coalesces with the concomitant right of the citizenry to appraise the judicial branch,” he wrote.

If Doe succeeds on his claim for damages, the judgment will be paid from taxpayer funds, he noted, so the public has a valid interest in knowing how the revenues are spent.

Doe’s Complaint

According to the amended complaint filed in federal court last December, Doe was hired in Lisbon in 2009. The trouble started when he sought reimbursement for his ballistic vest, which the department refused in 2011.

When the ballistic vest needed replacement in 2016, Doe again asked the town to pay for it, which was refused despite purchases for other officers, the complaint alleges.

When Doe complained about the vest issue, he was disciplined and only got a new vest after making demand through counsel, according to the complaint.

On October 15, 2020, Doe conducted his fitness test with the police chief of the Bethlehem Police Department, passed and submitted the form to the state of Police Standards and Training Council, which the council accepted.

Lisbon Police Chief Benjamin Bailey invalidated Doe’s passing test, the complaint said. Doe received a verbal and written warning for failure to perform a physical fitness test. That same day, Doe received a warning about failing to turn off lights, according to his amended complaint.

On Jan. 14, 2021, Doe was terminated as a police officer and Bailey notified the Attorney General’s Office that Doe would be placed on the Exculpatory Evidence Schedule.

Doe argued he was not afforded any opportunity to appeal prior to the EES notification. The complaint said he was not given the opportunity to assess or question his accusers and the EES notification was not based upon fact.

The federal court recently sent portions of the lawsuit back to the state Superior Court.

U.S. District Court Judge Joseph Laplante said the civil rights claims for damages against the town for due process and claims against the town for libel and attorney fees would remain in federal court.