By BEVERLY STODDART, A NH Writers Life

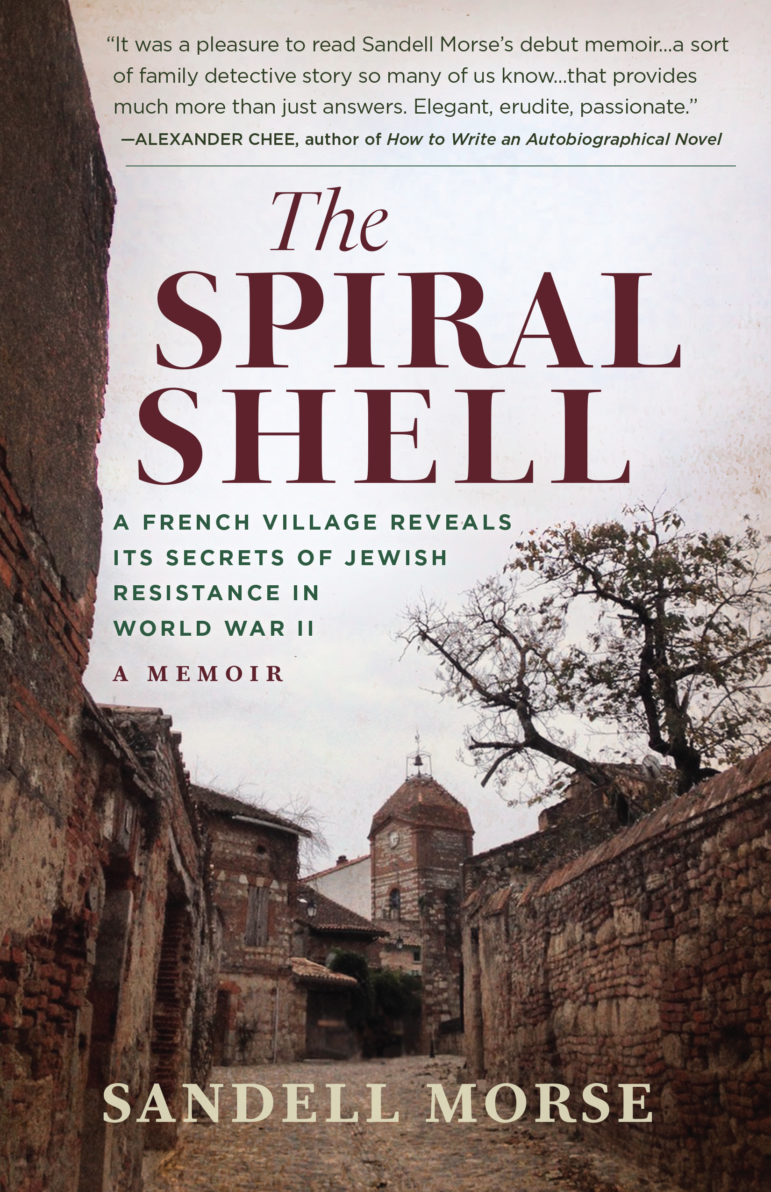

The Spiral Shell: A French Village Reveals Its Secrets of Jewish Resistance in World War II is a book by Sandell Morse, who lives in Portsmouth, that started out to be a book of essays. The book becomes so much more as she begins to follow “a trail of breadcrumbs” to the secret and dangerous ways the people of the French village of Auvillar fought to save the lives of Jewish people being hunted during the Second World War. Ironically, the trail begins with Jean Hirsch, who shares the same last name as her family. Jean leads Sandell to his father and mother, Sigismond and Berthe, resistance fighters who were turned into the Gestapo and eventually into the hands of Auschwitz’s Angel of Death, Josef Mengele. This beautifully written book takes us into the hearts of those who stood and faced certain death—people who helped Jewish children and the secret houses where they stayed. We begin by talking about her family and her Jewish faith.

You write in your book, “Mama’s gift: my deep love for Judaism’s soulful heart.” I love that line.

“Jacob and Henriette Hirsch are my paternal side great grandparents. They were German Jews. That’s why my father was so assimilated. The German Jews came over to this country much earlier, and there were few German Jews. Most of them did quite well in this country. They aspired to be like the prominent, dominant families in America. When the waves of Eastern European Jews came in the late 1890s, the German Jews were very much anti-semitic against them. They were not as cultured, and there were many of them. The German Jews thought they would ruin their place in America. My father married my mother, who has Eastern European Orthodox heritage.”

Your mother taught you to be proud?

“Mama is my grandmother. In Jewish culture and lore, like in German, the grandmother is muti. In our culture, the grandmother is Mama. I would call her Mama. But my grandmother, Rose, who is my father’s mother, I called Grandma Rose. Different cultures.”

Your father was not involved with his religion. Why? You have two distinct parents in their beliefs.

“My mother went over into my father’s camp. But we lived as an extended family with my grandmother, Mama, and Papa. Her parents were Orthodox and came from a place they called Russ-Poland. I would think it’s like Lithuania, somewhere like that. It was an area where Jews had to live in Russia. You couldn’t live anywhere in Russia. You had to live within these borders unless you had special permission.”

“The Hirsch family into which my dad was born, Jacob and Henriette, did very well. They were fairly wealthy, and they lived in a brownstone on Manhattan’s Upper Eastside. My grandfather was a dentist. He practiced in Newark, New Jersey. My dad grew up in a nice house in Newark, the youngest of two brothers. His father died when he was thirteen. That was a pivotal moment in his life. He always aspired to that class. He was always very assimilated. Jewish is a religion, just like Christianity is a religion. You are no different from anybody else. He would disdain a lot of the Jewish foods. That’s a way of people being kind of self-loathing. Yet, he lived in this house with my grandmother and grandfather, who were Orthodox. You’d probably call them more modern Orthodox. I grew up in a kosher house. My grandmother did all the cooking. She understood all of her children and grandchildren were eating treyf, non-kosher food, outside the house. She was kind and loving, and accepting of all. She’s the one who gave me the soul of Judaism.”

What starts you on this journey? What’s the trigger to write this book?

“I did not start on a journey to write this book. Yet, one main point of my writing the book was to affirm my Jewish identity.”

But a journey, nonetheless.

“I always seem to come in, slide in through the side door or the back door. Many writers do that. I can tell you how the book started and probably tell you when I knew I found myself on a journey.”

“I have written many novels and a lot of fiction but never published. I always say I had one foot in the door, but I never got the second one in. I started writing essays, and I liked it. I was on a residency in France in a little village called, Auvillar. I knew Auvillar was on the pilgrimage route, and it would be a crusader route. And if it’s a crusader route, I want to know about the Jews. I began researching. I knew a good friend who had been to this village and wrote poetry about some folks from the Second World War. She said I have a name for you. His name is Jean Hirsch. He was a nine-year-old resistance courier during the war, and he lived in Auvillar with his family.”

“I didn’t know anything about French history, and I went to talk to a dear friend, a rabbi. He said if you’re interested, there’s someone for you to meet. Her name is Valerie Fert. She and I developed this virtual friendship. She became my translator and my dear friend.”

“I started writing essays about Jean Hirsch and his father. Then Valerie introduced me to Germaine Poliakov. I was with her for an interview yearly for about eight years. Germaine one day said, would you like to meet one of the girls in the secret house? That’s when I knew I was on a journey. From Jean Hirsch, I went to Germaine to Yvonne. I began researching a lot about the village and talking to people in the village who knew things. I was following breadcrumbs from that point on.”

I love your writing style. Please talk about it.

“I’m lucky. I think I’m visual. As a former dancer, I like my prose to dance. I spent a lot of years going to the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. It’s a writer, composer, and artist colony in Virginia. I served on the board there for a number of years. The VCCA had converted an old barn into writers’ studios. There was this little kitchen, and it had a window that looked out onto a stone patio with a table and chair. I was in the kitchen looking out the window, and I saw an artist sitting there. She was just staring—nothing in her hands. Just sitting and looking. And I said to myself; I need to do that, sit and look.”

Talk about the village of Auvillar.

“That is where the VCCA operates a small writers’ colony in France. There are only four in residence. Usually, there’s always a composer, a writer, a visual artist, and one more of them. When you go, you’re expected to do a community project. We have readings with translators. The village is in the west of the country. It’s beautiful. There are palm trees and lush vegetation. It’s a medieval village. Everything is old. It is on the pilgrim’s route. What I loved most about it were all the flowers.”

What is the meaning of Vichy France?

“In 1940, the Germans marched into Paris and took France. The French government fled first to Bordeaux, and they made a deal with Hitler. The Germans would control the north of the country, and the French government moved to Vichy, a spa town in the south of France. They could govern the southern part from there. The head of the French government was Marshal Petain. During the Second World War, he became a collaborator with the Germans and did their bidding. I uncovered the extent of French collaboration in the round-ups and all of the horrors of that war. Vichy means the government of Petain. It means French collaboration with the Germans. It means a time of distress and shame. In Auvillar, you had sympathizers with the Germans, and then you had resistance, and they were all in the same area.”

In the book, you write, “The AJPN, a nonprofit organization headquartered in Bordeaux, collected Second World War testimonies and added them to an open online database.” This is where you find Jean Hirsch and his testimony.

“It is a site that recorded testimonies after the war. I found it while I was there the first time I had gotten the VCCA fellowship. I found his words, and Valerie helped me translate them. Jean Hirsch’s father was Sigismond Hirsch. He was a doctor.”

In the book, you write, “The Shoah was not one in a long line of genocides. It was unique. The killing of Jews had no political or economic justification. It was not a means to an end. It was an end in itself. Never before and not since has the world seen such systematic, bureaucratic evil, an efficient murder machine with the intent of exterminating an entire people, not just from one particular place but from the earth.” Why do you use the word Shoah?

“It is the holocaust, but I use the French word because I was writing about France. In French, it is the Shoah. Holocaust means the burning. In the book, I write, “The biblical word Shoah means catastrophe in Hebrew.” For me burning was a kind of extinguishing, an extinction, the reducing to ashes. Calamity is something that can happen again. Language carries a culture. So, I wanted it to be close to that.”

Let’s talk now about the Jewish Scouts. Tell us about their role in World War II.

“There were scouting organizations for years, and they were segregated. The Jewish Scouts were a normal scouting organization before the war. Their leaders realized they needed very early to save Jewish children during the war. So, they turned all of their organizational skills to rescuing Jewish children even before the war came to France. They ran a number of secret houses throughout the south of France that protected Jewish refugee children. They were couriers and resistance fighters. They created false documents and transported those documents. Jean Hirsch, the little nine-year-old boy whose father was Sigismond, and his mother, Berthe, led a resistance group in Auvillar. He used to ride from Auvillar to Moissac, a nearby village, on his bicycle, and hidden in the handlebars were messages he was carrying to his aunt and uncle who ran a secret house protecting Jewish refugee boys in that town.”

The Hirsch family you write about is not related to you.

“No relation whatsoever. None of the Hirschs I write about are related. I wanted to connect with Jean Hirsch to talk about the village of Auvillar. I did not want to connect about my ancestry. I felt a connection to him because I knew that somewhere down the line, we could have been, might have been related. Hirsch is a very common Jewish name in the Alsace area where my family came from.”

But he won’t speak to you.

“Gerhard Schneider, an academic interested in Auvillar’s Jewish history, would tell me Jean Hirsch was very traumatized by the war. Jean wrote a book in French, not translated, and I could not read it. He wants to let it rest. Jean said I have said everything in my book. At that point, he was in his late seventies and has since passed away. He would make dates to meet with me and then cancel them at the last minute. I think he just couldn’t.”

We now meet Germaine Poliakov. In the book, you hear from Valerie Fert, who says, “Since you wrote to me, I have tried to think of people I knew who lived through the years of Vichy that I could introduce to you. Tomorrow, I will take you to meet Germaine Poliakov. She is a widow. Her husband was a famous French historian, Léon Poliakov.”

Photo courtesy of Sandell Morse.

“First, let me say she passed away in February of 2020 at 101. There’s a scene in the book where I describe her, and I still can see her standing at the door of her flat in Paris, leaning on her cane. There is blue in the dress she is wearing. Watermelon pink lipstick. The dyed red hair so common among French women. She was wonderful, my kind of woman. Strong, outspoken, energetic. She was a singer, and when I met her, she was ninety-two, and she still had music students. She had written a small book about teaching music. She was making collages of dried flowers she collected. She lived on the fifth floor and still walked up and down those stairs twice a week to go to the grocery. She was interested in life, her entire life.”

What is her history with the Jewish Scouts?

“When she was very young, she was a Jewish Scout. She went to school at the French Academy of Music when war broke out, studying music and voice. As soon as the Nazis came in, her career was ruined. Her father rented a flat in the south of France for his family before the mass exodus. The belief was Paris would be bombed. They had to get out before that. They realized then Hitler was not going to bomb Paris but make it the jewel in his crown. Germaine’s father, mother, and two of her sisters returned to Paris, and they passed as Christians during the war. Germaine did not want to go back and one day met her old scout leader on the street, and that was Madame Gordin, who was running this secret house. Madam said to her, Germaine, I need you to help me manage these girls. And she said to me, I had nothing better to do, so I said yes. She was twenty.”

There’s an amazing scene you write about in the book. “I was…” Germaine rounded her hands and drew a dome in front of her belly… “expecting my third child, carrying my baby in one arm, dragging Daniel by his hand, and running across a field to the woods. I heard a shot. I knew what it was. I wasn’t frightened. I felt calm. I don’t know why.”

What kind of book were you writing at that time?

“I was writing a book of essays about Vichy France and Jews resisting. I was writing my connection to these people and how my beliefs had changed when I learned the reality of that time. And how my father’s voice contradicted so much of what I was finding out.”

How is this a memoir?

“It’s my spiritual journey. What kept drawing me to Germaine’s story was the secularism of the French Jews and the assimilation of the French Jews, and the way they loved their country, yet after the war could not say they were Jewish. They were ashamed. The French Jews, after the war, reminded the French of all they wanted to forget, and that was collaboration. Don’t forget when the French Jews came back they were no longer were in possession of their homes and their places of work. The immigrant Jews were the ones that were mostly murdered. The French Jews knew better how to survive.”

Germaine introduces you to Yvonne.

“Yes. I thought Yvonne was French. She was German. Her family had been in Germany in a town at the Rhine River for four hundred years.”

Was she Jewish? Was she one of the hidden girls?

“Yvonne was Jewish. It was a secret house, but they weren’t hidden children. Hidden children are the children who lived like Anne Frank. They are living very openly in this village, and that is what’s remarkable to me.”

“Yvonne was nine years old when the war broke out. She remembered and talked to me about this a lot. I had never been that close to one who had been through that horrible night in November 1938. Her sister was three years older. Her father was arrested on Kristallnacht and sent to Dachau, but Dachau was not a killing camp then. It was a concentration camp. She gets sent to her father’s sister in France. She was very itinerant for a long time. Then she was dropped off at the la colonie, the house that protected Jewish refugee children, and Germaine became her caretaker. Germaine was twenty, and Yvonne was nine or ten years old.”

Kristallnacht is that horrible night in Germany where they burned Jewish-owned stores, buildings, and synagogues. You connect her to Germaine and the scouts. You use the phrase of finding your story by “coming in through the back door.” You have these discoveries.

“What I learned about myself recently is that everybody doesn’t do this. But for me, it seemed natural. This is a connection, and I think I’ll follow it.”

You write, “The best way to find what I was looking for was: let it reveal itself.” Is that what you’re saying?

“Yes, I think so. That’s truly what it’s about. Just go. I had to learn this very late.”

Why so late? What would stop you?

“My father’s voice in my head. You can’t do that. What, are you crazy?”

What is the la colonie and the secret house?

“They called it the secret house, but it was visible. Clearly visible in the village of Beaulieu sur Dordogne. That’s the other thing I learned. There was Communist resistance. There was a Catholic resistance and a Jewish resistance.”

All fighting for the same purpose? Getting rid of the Nazis.

“Yes. They would fracture later, but all worked on getting rid of Hitler.”

Two words: collaboration and deported. Please talk about how these words apply.

“Collaboration was turning in Jews. Sigismond Hirsch was arrested one night by the Gestapo. I just knew an officer arrested him. Mary Jo Schneider, who, along with Gerhard, founded the French and German Cultural Society, said to me one night, yes, but who told him? That’s when I realized collaboration was giving information to the Germans.”

“The word deported is loaded. It can mean in the sense of Vichy France, when you were deported, meant you were going to a holding camp, like Septfonds, the one I visited. Then you went to a transportation camp. Then you were going to a concentration camp which meant almost certain death.”

I found the word deported lacking.

“That’s the point. Germaine did not want to bring things back. Everybody talked about the deportation of the Jews. It was a euphemism. I also think what was revealed to me doing this work, even though I knew about the systematic and the bureaucracy of deportations, I didn’t see how they worked until I was there. An order would come to the local gendarmerie. You had to round up on that day. You had to have enough transportation on that day. Then you took them to a localized holding camp where they stayed until the transport camp was empty. Then you filled it up again. You have a local train line. And everyone comes from all over to the transportation camp and then to the killing camps. And then it starts all over. Can you imagine?”

I have never heard it described like that. The organization. Logistics in the worst way.

“Deadly.”

Back to Sigismond and Berthe. I was reading your book from my Kindle app on my phone. I don’t sleep well. I’ll read during the night. I read this, “Berthe, thirty-seven, was gassed on arrival. Sigismond, also thirty-seven, was sent to work for Mengele.” I had to stop reading and get away from that thought of the Angel of Death.

“That’s the closest I’ve been to that, too. Someone said to me; it must have been hard to do all this. I was so immersed that something was sort of protecting me and keeping me going. Right now, it’s so painful. It’s horrible. You know these things because the Germans kept meticulous records. You can find this out. You can find the numbers of the convoys they were on. I don’t know what document I found that specifically in, but, yes, that’s what happened.”

You go to the house and the garden where they were arrested.

“Yes, I had to go. I had to see because, as I say in the book, place remembers. I wasn’t going to let that stop me. I go into the garden. They were both crouching underneath bushes trying to hide.”

Someone told somebody they would be there.

“Yes, at that meeting of the resistance. They came that night just to arrest Sigismond and Berthe. They didn’t take anyone else because they didn’t have an order to take another.”

They would have to have a written order to take someone?

“Absolutely. That’s another thing people don’t get. Until there was a specific order, people went to buy a loaf of bread. They lived. Until their moment came when they would come home, someone was at the door. What do you do? You live.”

Sigismond, in Auschwitz, ends up working for Mengele.

“Jean Hirsch wrote about his father. He says in his testimony, his father read X-rays.”

Do you buy that?

“Of course not. But that’s what people had to do to protect themselves. His father had nightmares all the rest of his life.”

He survived. There’s guilt in surviving and collaboration. He returns to Auvillar to thank them for saving his children.

“They did save Jean. A convent of nuns in Auvillar saved him. First, I found out there was this little boy who was this courier. Then I went to Paris and found a woman who lived in a secret house. And then I find out that there’s a child in one of those houses, and I come back to Auvillar, and I talk to Gerhard. He tells me more about Jean Hirsch, Sigismond, and Berthe. I found out how much the gendarmeries were involved in the arrests. It just kept going.”

Back in Paris, you wandered the Marais, the Jewish Quarter. You read a plaque about 260 children taken one day from school. It reads, never forget.

“How do you look at never forget? It is a way of acknowledging to yourself this horror, but we do forget. We do it again. Maybe we remember, but we repeat. Never forget means we repeat. Genocides are going on right now.”

I kept looking throughout the book for the source of the title, The Spiral Shell. You join a walking tour in the Marais, and the guide, Brian, points to the limestone block and traces his finger in the grout. You write, “Nearly all of Paris was constructed of limestone dug from deposits that dated from a time when France was once an inland sea.” What do you see in the limestone?

“I saw the indentation of a shell. Brian found a shell in the pebbles and gave it to me. (Sandell shows me the shell.) It was a good metaphor because of the way things do spiral up. The book is about attitudes, values, survival, how much it takes to survive and how little it takes to help someone survive.”

You write, “You don’t need a personal connection to feel the horror, the injustice, and the cruelty.”

“Right. I believe that.”

Beverly Stoddart is a writer, author, and speaker. After 42 years of working at newspapers, she retired to write books and a blog. She is on the Board of Trustees of the New Hampshire Writers’ Project and is a member of the Winning Speakers Toastmasters group in Windham and the Ohio Writers’ Association. Her latest book is Stories from the Rolodex, mini-memoirs of journalists from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. A prized accomplishment was winning Carl Kassel’s voice for her voice mail when she won the National Public Radio game, Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me! She has been married for 45 years to her husband, Michael, and has one son and two rescue dogs.