Photo courtesy of Paul O. Jenkins

“Give me rhythm

In its fullest measure

Wild harmonies we never learned in school

If this is what they’re calling foolish pleasure

You’re looking at an ever-ready fool!”

“Foolish Pleasure” written by Raymond K. McLain

By BEVERLY STODDART, InDepthNH.org

Paul O. Jenkins of Goffstown is a librarian. He is the University Librarian for Franklin Pierce University. I make clear to anyone who will listen I know librarians are superheroes in comfortable shoes who have faced the internet and didn’t blink.

We turn to these amazing people for information, in this case, bluegrass music information. Paul O. Jenkins loves music, and musicians, especially lesser-known musicians like Richard Dyer-Bennet, who “was among the best known and most respected folk singers in America.” Paul’s book titled Richard Dyer-Bennet: The Last Minstrel details Dyer-Bennet’s many achievements.

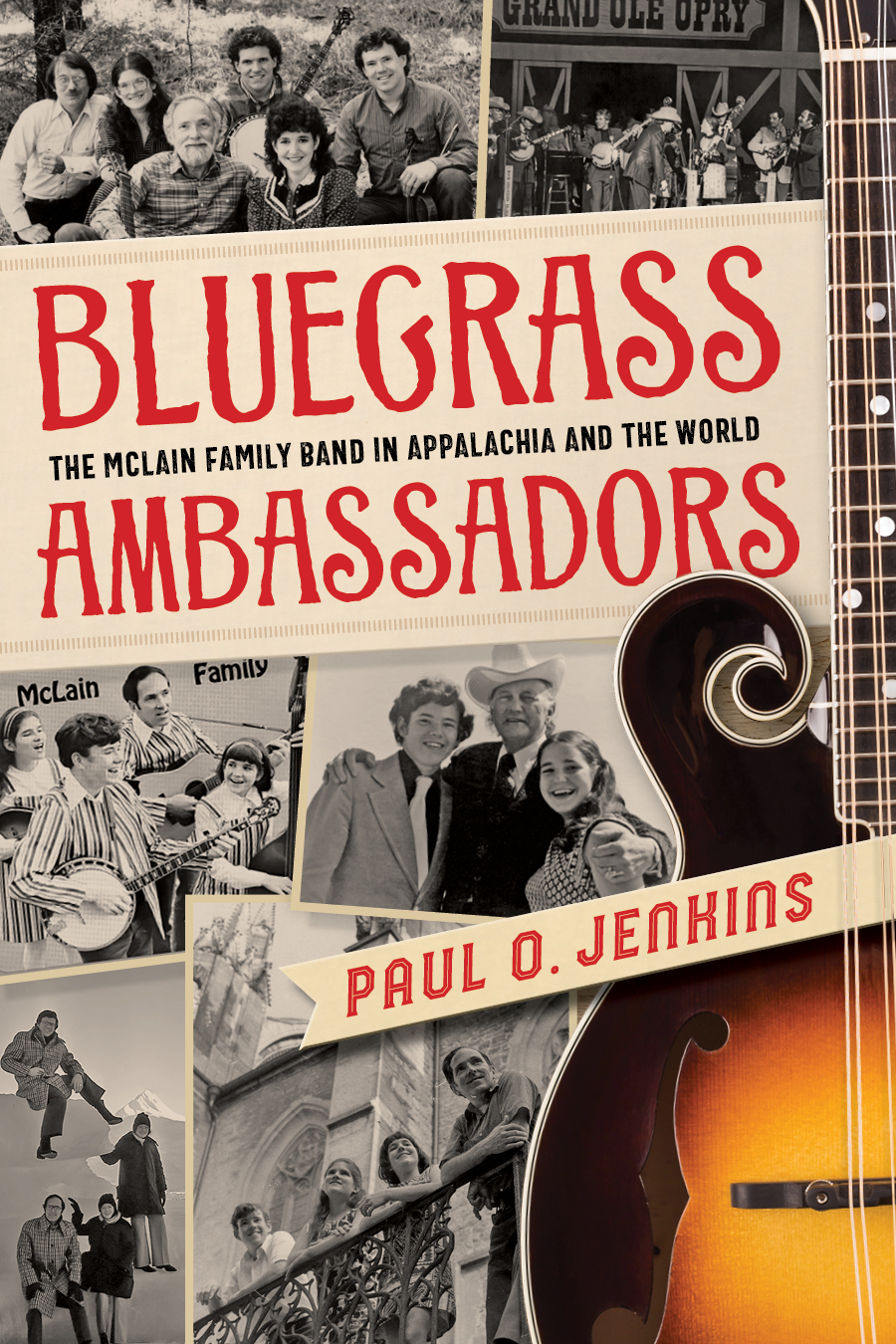

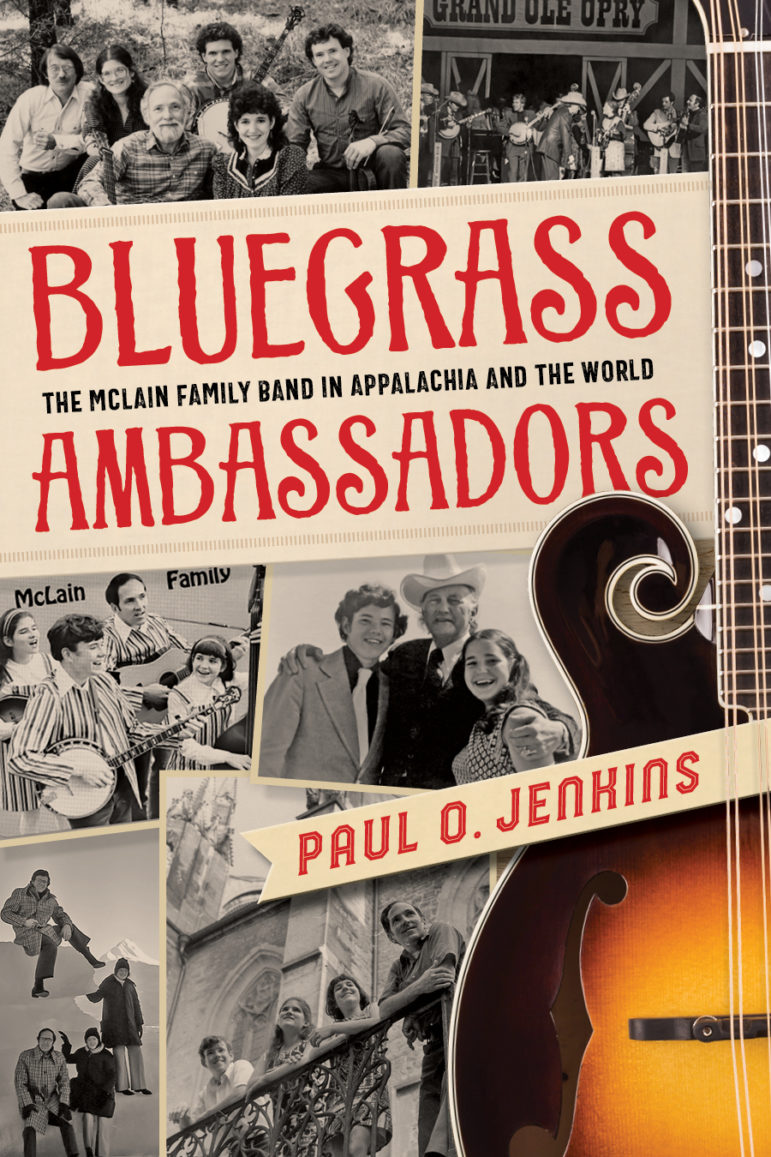

In his new book, Bluegrass Ambassadors, The McLain Family Band in Appalachia, and the World, he turns his talents for research and the love of bluegrass music and takes us into a world of the McLain Family.

My interest was piqued when I read the patriarch of the McLain family, Raymond Kane McLain, taught bluegrass music courses at Berea College in Berea, Kentucky. My grandfather, William Robinson, attended Berea College. Those unfamiliar with this Kentucky college should know no student pays for tuition at Berea. Instead, they are required to work in return for tuition. Berea College was the first “integrated, co-educational college in the South. And it has not charged students tuition since 1892.”

Paul’s book is a part of the Sounding Appalachia series presented by the West Virginia University Press-Morgantown. He begins his book with the dedication: “To Owen, who loved how Ruth “beat up on” her bass.” And then, we are given the McLain Family tree to keep the “Raymond’s” straight.

Raymond Francis McLain married Beatrice “Bicky” Kane. Their son, Raymond Kane McLain, married Mary Elizabeth Winslow, and they had five children who would become the McLain Family Band. The first-born son was Raymond Winslow McLain. Daughters Rose Alice, Ruth Helen, and Nancy Ann came next, followed by the second son, Michael Kane McLain.

What is bluegrass music?

I dove headfirst into the challenge of the depth of understanding bluegrass music by asking Paul to explain what bluegrass music is.

“That’s a very interesting question. There’s an old saying WIBA – What is Bluegrass Anyway? It’s a very contentious topic. Some people will say and will mention an artist, and another will say that’s not bluegrass.”

“I have an actual quotation here. Raymond K McLain, the father of the McLain family, described bluegrass this way, “Bluegrass has the sincerity of the Anglo-Saxon ballad, the hoopla of the minstrel show, the social ability of the singing game, and the square dance, the loneliness of the cowboy life, the sass of ragtime, the fervor of the camp meeting and the pathos of the blues.”

“I like the use of sincerity in that quote. I think one of the elements of bluegrass is its tremendous sincerity, something that’s shared with country music. There’s something called old-time or mountain music, which is related to bluegrass. Bluegrass music features virtuosity in the instrumentation in a way that old-time or mountain music doesn’t. They’ll be somebody flailing on a banjo in mountain music. It’s kind of its background. In bluegrass, the accompaniment on the banjo would be much more sophisticated, and it probably would be a three-finger roll style that Earl Scruggs popularized. It can get very complicated.

“Other people call bluegrass music folk music on steroids because it’s taking a lot of the elements of folk music, which the main thing there is acoustic instruments and no drums, and it’s amping it up and speeding it up and putting a little extra oomph in it. So, there are all sorts of definitions of bluegrass music. And then some people say it doesn’t have a banjo in it. It can’t be bluegrass. But that’s wrongheaded as well. Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass, played the mandolin. When he started with his brother, as the Monroe Brothers, there was no banjo. Yet he’s the father of bluegrass music.” (Note: According to CountryMusicHallofFame.org: “In 1945 Monroe added the revolutionary three-finger banjo picking of Earl Scruggs, which provided bluegrass with its final building block.”)

“Most people who think of bluegrass music think of Flatt and Scruggs, and they came from the Monroe tradition. Both of them had played with Bill Monroe earlier in their careers. When Earl Scruggs’s banjo came in, that’s what people think of bluegrass music: banjos, fiddles, mandolins, and usually no drums. Occasionally there are drums in established bluegrass music. That’s contentious as well. JD Crowe, a very famous bluegrass artist, had drums and some people thought that was anathema. Sometimes you’ll see an electric bass. And others will say, no, you can’t do that. It has to be a standup electric bass. I think that’s a very complex answer to your question. You get a distinction of how passionate people are about the purity of the music.”

Do you love it?

“Yes, I love bluegrass music. I say in the introduction of the book I did not listen to a lot of bluegrass music early in my life. I was mainly a Beatles guy. I’ve written a book on the Beatles. I co-edited a book called Teaching the Beatles with my brother, who also teaches courses on the Beatles as I do.

I grew up listening to the Beatles and also was very big on people like Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston, and also very big into Irish folk music. There are connections between Irish folk music and bluegrass. One day my dad, an English professor at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, came home with this stack of bluegrass albums by the McLain family. The McLain’s had played a concert at the college. He bought all these albums. This would have been about 1977-1978. I loved the singing. I loved the instrumentation. I loved the topics brought up in the music and the melodies. I loved everything about it. I began to listen to all the big names, Flatt and Scruggs, Bill Monroe, and the Monroe Brothers. No other bluegrass group I listened to appealed to me as much as the McLain’s did. I started thinking about the difference between the McLain’s take on bluegrass music compared to all the other celebrated practitioners. I thought of this as an abstract exercise for years and years, and when I moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, I realized I was two hours away from Berea, Kentucky, which is where the McLain’s started.”

“I had written a bunch of articles about musicians, and I’d written a book about a famous singer from the 1950s, Richard Dyer-Bennett, and I thought maybe my next book would be about the McLain family. I went to the archives in Berea, Kentucky where the college has extensive holdings on the McLain family. I started to explore more about the band. It was terribly intriguing. They taught bluegrass music. They toured sixty-two foreign countries as bluegrass ambassadors. It was seven years of my life researching this book and finding the right publisher. Doing the revisions. Getting the permissions to use photographs and lyrics.”

Fitting into bluegrass lore.

How do the McLain’s fit into bluegrass lore?

“Raymond Kane McLain was trained in classical music. He liked folk music because his father, Raymond Francis McLain, a big name in higher education, was married to a woman named Bicky, who was into folk dancing. So, Raymond K was influenced by his mother, Bicky.

Even though he was studying classical music, in the back of his mind, Raymond K decided he liked folk music best. He decided to move the family to Hindman, Kentucky, and took a job at the Hindman Settlement School. He started to raise his family and created a bluegrass band, bit by bit, as his family grew. Father, Raymond K, played rhythm guitar. His oldest son, Raymond W, became the virtuoso of the group. He’s a very good banjo and fiddle player, mandolin player, and guitarist, a good singer too. His younger sister, Alice, played mandolin and bass and was a good singer. Her younger sister, Ruth, was a singer and bass player and mandolin player. Ruth excelled on the bass. She does a technique called slap bass.” (Note: MusikaLessons.com describes slap bass as, “By slapping the strings, bassists can get a distinct percussive sound they couldn’t have gotten by picking or plucking the strings. Also called “popping.”)

Understanding the McLain family members.

You are the university librarian (Library Director) at Franklin Pierce University. It came out in the book. The book showed your expertise with two appendixes, chronology, a discography, notes, bibliography, and index. You covered all your bases. Talk about them as players and people.

“Raymond K was the founder of the band and a guitar player. Raymond W played fiddle and banjo. Alice sang, played bass, and mandolin. Ruth played bass and mandolin and sang. That was the core group. Later on, Nancy Ann became a singer, bass player, and clog dancer. And then finally, the youngest son, Michael, became quite a good guitar player.”

“The group, as the years progressed, sort of had interchangeable pieces to it. Al White married Alice, and he became part of the group. He was from the American Southwest, and he brought in the Bob Wills swing music element. The core group was the father. Raymond K, son, Raymond W, and daughters, Alice and Ruth.”

Give me one sentence on each individual. Let’s start with Raymond Kane McLain.

“Raymond K: patriarch, erudite, scholarly, professional, organized leader and arranger of the songs.”

“Raymond W: oldest son, he is the group’s virtuoso, leader, innovative, gregarious, and friendly. They were all so friendly.”

“Alice: the oldest daughter, teacher, excellent singer, and organizer. She was the one who wrote to various embassies and advertised the family was willing to perform in foreign countries.”

“Ruth: also, a teacher, an organizer, team player, and a facilitator. She helped everybody come together and be on the same page. She worked with me most on the book.”

“Michael K: He’s very good at production. When the band went their separate ways, he’d be the sound engineer and producer. He was the best guitar player of the group.”

“Nancy Ann: Her main contribution was a clog dancer. A good bass player and singer.”

How was their music different from traditional bluegrass.

“They covered a lot of traditional bluegrass pieces, but what set them apart was their original music. That was mainly Raymond K (father of the band) who wrote a lot of songs like “My Name’s Music, or “Foolish Pleasure.” Much of the music was about the pleasure music can bring to life. That is what sets them apart in their material. Their approach set them apart as they were tremendously cheerful. They almost got dinged in the bluegrass press because they were too cheerful. You’ve heard of the high lonesome sound of bluegrass music. The very word lonesome indicates sadness in the music. The McLain music was more cheerful than most bluegrass music. And some critics thought they were too cheerful. One of the critics named John Hartley Fox claimed, “the dark and haunted side of bluegrass is completely absent from the McLain family. Some see this as a plus and others as a minus.” That was the kind of thing that haunted their career. People thought they were great, but they weren’t sad enough to be bluegrass. A ridiculous claim.”

“They were good at the sad songs too. However, the main impression you got was this cheerfulness. And what’s wrong with cheerfulness, for God’s sake? One of the primary roles of music is to provide a balm to all the cares of daily life.”

Why are the acknowledgments at the beginning of the book? Aren’t they usually at the end?

“I like to set the table and say before you read anything in this book, here are the people I need to thank. Here are the people who made this possible. That’s why I put it at the front.”

And you wrote, “thanks for letting me share their foolish pleasures.

“It’s a pun on one of the songs Raymond K wrote called “My Foolish Pleasure.” It was a pun in the song, too, because there was a horse named Foolish Pleasure who raced in the Triple Crown races. The lyrics go, “some say my music is just a foolish pleasure,” and the rest of the song says, “it’s not just foolish pleasure; there’s more to it than that.”

Were there ever any family issues? Were they always happy with themselves?

“Yes, when you spend so much time on the road and the stresses, they stayed as a cohesive working unit. I asked them this question too. By all accounts, they kept a very good relationship with themselves. They knew they had to work together as a team. They each kind of knew their role in the family. They were a bit old-fashioned as they respected their father a lot and he set the pace and controlled things, which helped. As a family who grew up in Appalachia, the role fell to the father.”

Berea College

Let’s talk about Berea College. Not everyone will know this college. Tell me about the institution of Berea College and then tie it to the McLain family.

“Berea is often called the Oberlin of Kentucky, which is a big compliment as Oberlin in Ohio is an outstanding school. I like to say an exceptional band found a home in an exceptional college. Berea doesn’t charge admission to its students. One of the ways the students make up for the way they don’t pay tuition is that they all have to have a job on campus. Often this involves various crafts. Berea College’s craft store is famous, and you can order things via the mail and over the web. They were one of the first schools to welcome African Americans. In the nineteenth century, a lot of African Americans weren’t allowed to go to college. Berea was one of the first places to welcome students who weren’t white. That’s another thing that makes Berea exceptional.”

“When Raymond K, the father, was the director of the Hindman Settlement School, he was offered a job at Berea by a man named Loyal Jones. He knew Raymond K’s work and wanted him for Berea College because he felt Raymond K embraced the same values Berea held. He took a job at Berea College, and he taught music classes, some more traditional folk music, but he was one of the first to teach bluegrass music at the college level at Berea. Berea became very well known for that, and a lot of students came to the college for that reason. The McLain kids ended up going to Berea too. They were there half the year, going to classes and then on the road. It was an intimate connection with the band and Berea College.”

“The campus is beautiful, and there is a friendliness to the campus. Every college has a culture, and Berea’s is welcoming, friendly, embracing, positive, and cheerful. That fits right in with the McLain family. It was a match made in heaven.”

Women in bluegrass.

Will you talk about the prominence of women in bluegrass acts? They are right up front.

“There have been females in bluegrass groups before. The McLain’s were part of the vanguard of this. There’s a book by Murphy Henry called Pretty Good for a Girl. It’s devoted to the history of bluegrass music, and the McLain’s have a chapter devoted to themselves. Alice, Ruth, and later on, Nancy Ann were not in the background. They were a big part of the band. That was inspiring to many young girls who would see them perform. Often entire families would come to see them play because it was a lot more of a family act. Little girls would draw inspiration from them. It’s another great part of their story of bringing female musicianship to the fore. A lot of time, females had been singers in the groups. But not as much as prominent musical members. Ruth was a very innovative bass player. She’s a small woman, and when she was young, she had to stand on a box to play the bass.”

Classical Crossover

They do the most unusual thing. They cross over to classical.

“There was a composer named Phil Rhodes, and he got to know Raymond K and saw the McLain family band perform and said, I want to compose a bluegrass concerto specifically for your family band. That’s how impressed he was with their musicianship. Even though their father was a classically trained musician, he made a conscious decision not to teach his children classical notation, how to read music. He wanted them to experience it naturally and organically instead of learning scales from written notations. When Phil Rhodes wrote the concerto in standard notation, the question was how does the group learn this to perform it with a symphony orchestra?”

“This is a fascinating story. They just memorized the parts, and they came up with their system of remembering where to come in. It was a challenge for the classically trained musicians as they had to work with musicians who weren’t going by the score. They tackled and mastered this complicated process, and it became a mutual admiration society. The classically trained musicians were amazed they weren’t following the score. They memorized their parts. It was a great union of two different traditions and the down-home untrained style of the bluegrass musicians. Phil Rhodes bridged the two traditions, and he did it in a very seamless manner. They performed this concerto hundreds of times with different symphony orchestras all over the country.”

Ambassadors of Bluegrass Music.

Chapter seven of your book is “On the Road.” Talk about their travel. It looks like this little bluegrass group takes the world.

“That’s exactly right. The McLain’s are recognized as spreading the gospel of bluegrass all over the world. They performed in sixty-two foreign countries throughout a ten-year period. They operated under the auspices of the US State Department. They were keenly aware they were representing America and all the good parts of America. Many in the audience had never heard bluegrass music before. If you’re in the Congo, you’ve never heard bluegrass. They didn’t understand the lyrics. But it was the feel and the joy that the McLain’s brought. They would learn the traditions of the country they were visiting to fit into the cultures they were performing. Some countries didn’t applaud after a song. This was hard for the McLain’s, but they knew not to take offense. They would learn songs in the language of the country they visited. That cemented the bond with the band and their audience. They sought out opportunities. Alice played a key role in writing to representatives of the State Department saying they wanted to perform in a country. All they asked for was a basic stipend and living expenses. They embraced these opportunities. They did it for the experience and were financially supported by the US State Department with help from cultural attaches. They were doing this in the 1970s and 1980s. It was tremendously complicated to coordinate all this.”

The McLain Family Legacy

What is their legacy?

“They celebrated their 50th anniversary a couple of years ago. Raymond K is dead. Raymond W, the oldest son, is the leader now. But it’s a team effort. One of their legacies is their educational links. Raymond Francis, the grandfather, was president of Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky. He was president of the American University in Cairo, Egypt. Raymond Kane, the father, taught at Berea College. Raymond Winslow, the oldest son, became director of bluegrass music programs at Eastern Tennessee State University and Morehead State University in Kentucky. Ruth teaches at Morehead State. Michael, the youngest son, was the head of a bluegrass music program at Belmont University. Alice was an elementary school teacher. So, you can see that education runs through their family, and they have instructed so many college students in the history of performing bluegrass music. There are hundreds of performers out there now who can trace their musical skills to the direct influence of the McLain’s. They are propagating the traditions of bluegrass music. That is one of their big legacies. Along with that is the bluegrass ambassadorship and then the cheerfulness and celebration they brought to bluegrass music through the songs they performed themselves.”

“The McLains performed at Carnegie Hall. They performed at the Grand Ole Opry. I want to let people know that this is a very important group and go and listen to their music. I hope the book inspires people to listen to their music.”

Beverly Stoddart is a writer, author, and speaker. After 42 years of working at newspapers, she retired to write books and a blog. She is on the Board of Trustees of the New Hampshire Writers’ Project and is a member of the Winning Speakers Toastmasters group in Windham and the Ohio Writers’ Association. Her latest book is Stories from the Rolodex, mini-memoirs of journalists from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. A prized accomplishment was winning Carl Kassel’s voice for her voice mail when she won the National Public Radio game, Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me! She has been married for 45 years to her husband, Michael, and has one son and two rescue dogs.