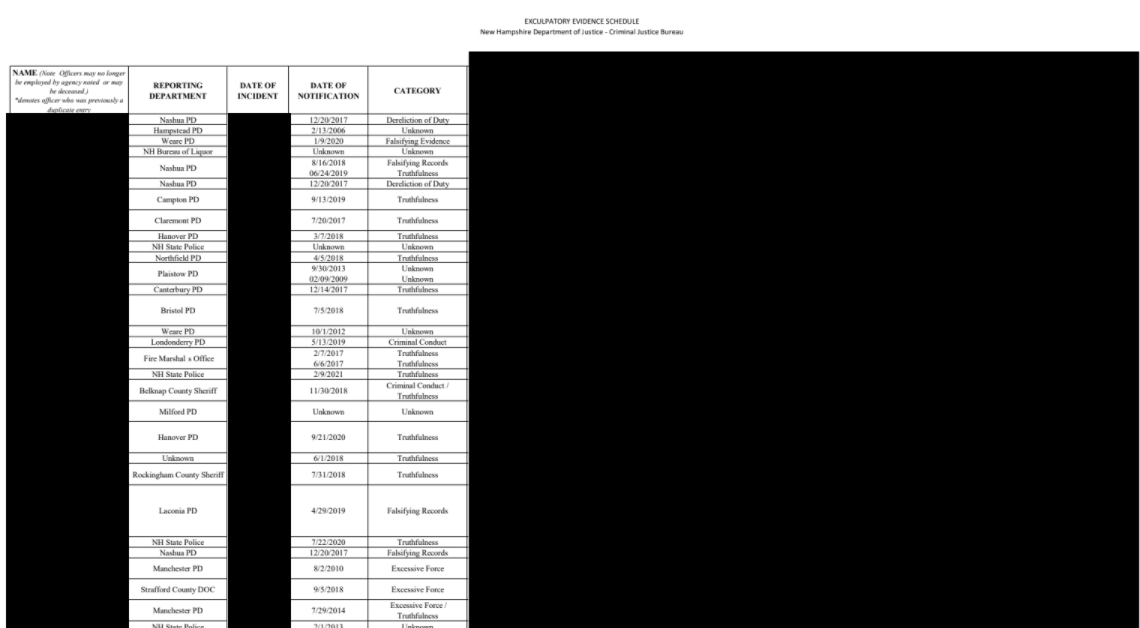

Oct. 22 Exculpatory Evidence Schedule, also known as the Laurie list provided by the Attorney General’s Office: https://indepthnh.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RTK-BS-pgs-1-7_Redacted-1.pdf

By NANCY WEST, InDepthNH.org

The attorney general has removed 28 confidential names from the Laurie list of 281 dishonest law enforcement officers before the process in the new law requiring a judge to make that decision has had time to be fully implemented.

The names were taken off using the attorney general’s 2018 removal protocol with about half of the 28 names taken off in the last two months, according to Senior Assistant Attorney General Geoffrey Ward.

“There are 28 now removed,” under the protocol, Ward said.

Taking the redacted names off the list just as the new law allows officers to file a lawsuit in Superior Court to argue before a judge why their names should be removed before the list is made public doesn’t sit well with some defense attorneys.

“We don’t think anyone should be removed from the list without judicial review,” said Manchester Attorney Robin Melone, a member of the New Hampshire Association of Criminal Defense Attorneys board.

“It certainly smells funny that now that they are going to be public, people are being removed and they are not having to go through the (court) process” in the new law that went into effect Sept. 24, Melone said.

The state is working toward transparency, she said, but the attorney general’s 2018 protocol is not a transparent process.

“It’s concerning that anyone would be removed from the list. And the fact that 28 names are being pulled off the list, that’s 28 people whose names will not be disclosed of people who were placed on the list for a reason,” Melone said.

Ward said under the protocol, another 11 names could be removed.

Attorney General’s Protocol

It is a separate process from the one outlined in the new law RSA 105:13d. The new law required the attorney general to notify the 281 listed officers in late September of their chance to argue in Superior Court why their names should be removed before the list is made public.

Ward said only 257 notifications were sent out because of the number who were being removed, or the state had no contact information or they were deceased.

Officers have been placed on the list, which is now called the Exculpatory Evidence Schedule, because they had sustained discipline for dishonesty, excessive force or mental illness in their confidential personnel files.

Such evidence must be disclosed to criminal defendants and prosecutors use the list to flag officers where disclosure is necessary.

Under the new law officers and former officers have either three or six months to file in Superior Court seeking removal depending on when their name was added.

Since there is no way of knowing how many will file, how long it will take to wind through the court system, or how judges will decide, there is no way to know how many names will remain on the list when it is finally made public.

The earliest any names could be public is Dec. 29.

“I can’t speak to what this list will look like in its final format,” Ward said.

“But I think what we’ve made clear – and I think has gotten lost to some extent in the focus on the EES – is that my obligation, any prosecutors obligation in any case, is not simply to check the list and go from there,” Ward said.

Instead, the prosecutor should make inquiries of the officers’ department to make sure all exculpatory evidence, or evidence favorable to the defendant, is disclosed to the defense.

New Wrinkle

The attorney general’s 2018 removal protocol requires officers produce an order from an arbitrator, or from a court that has reviewed the circumstances that required placement on the list and made a finding that in essence those circumstances did not occur, Ward said.

But some of the most recent 14 officers were taken off the list because they were erroneously placed on it, Ward said.

“Some individuals had been included on the list who were not sworn law enforcement officers and the list per our protocol is for sworn law enforcement,” so they did not qualify and were removed, Ward said.

Those included corrections officers and others in unsworn areas of the department of corrections such as probation or parole supervisory personnel, Ward said.

“Other state agencies may come in contact with the criminal justice system but are not sworn law enforcement officers,” Ward added.

Ward provided this example for corrections officers: “They go through a different academy than police officers…They go through the corrections academy, so they are sworn corrections officers, but not sworn law enforcement officers.”

Defendants’ Rights

Keeping the list intact and making it public is critical to criminal defendants who were convicted but were not aware that an officer testifying against them had undisclosed exculpatory evidence in their personnel file.

If a criminal defendant finds out after their conviction that such evidence existed, even many years later, he or she can petition the court for a new trial or try to have the charges dropped altogether.

Any names removed before the list is public won’t be accessible to criminal defendants.

Melone believes the list is very limited and that prosecutors must use all means to determine if officers have Laurie issues.

There may be times when issues in a police personnel file should be disclosed even if they don’t meet the requirements of the Laurie list, Melone said.

For instance an officer may have been involved in three cruiser accidents and the case involves charges against someone for crashing into the officer’s cruiser but the defendant is arguing it was the officer’s fault. That information should be disclosed, she said.

Melone believes there should be a system wide review of past cases, but said it should not fall on over-burdened prosecutors and defense attorneys.

Every defendant should have the right to simply write a letter to the attorney general and ask if there had been undisclosed exculpatory evidence in their past case whether or not it was documented in a police personnel file.

“Part of our concern is the list will continue to be dysfunctional and not representative of all information that is potentially exculpatory,” Melone said.

“Our stance is that the law that was passed is designed to increase transparency but the constitution mandates that prosecutors produce any and all exculpatory evidence including information in personnel files. It is not limited to what is included on the list,” Melone said.

Controversial

The Laurie list has been controversial since the public first learned almost a decade ago that prosecutors keep secret lists of officers with sustained discipline in their confidential personnel files that could negatively reflect on their credibility to testify in court.

The U.S. Supreme Court in the Brady v. Maryland case over half a century ago made it clear that criminal defendants must receive all exculpatory evidence, or the conviction could be at risk of being overturned or the case tossed out altogether.

The constitutional guarantee of all favorable evidence for criminal defendants was brought home in New Hampshire in 1995 when Carl Laurie’s murder conviction was overturned because then-state prosecutors John Davis, now a federal prosecutor, and Diane Nicolosi, now a Superior Court judge, withheld evidence that the main police investigator in the murder investigation was known to have been disciplined for dishonesty and other serious issues.

Law Enforcement Rights

Getting off the list is important to law enforcement officers because of the damage it does to their careers. Some departments fire officers with the Laurie designation because it would be problematic for them to testify in court where their credibility could be questioned in front of a jury.

New Law

The new law is the culmination of negotiations between the Attorney General’s Office, ACLU-NH and five newspapers seeking to resolve a lawsuit filed by the news organizations seeking to make the list public. Lawmakers added it as an amendment to another bill.

Hillsborough County Superior Court Judge Charles Temple has already ruled the list to be a public document. The attorney general appealed to the state Supreme Court, which also found it is public, but sent it back to Judge Temple to rule on whether the officers on the list have privacy interests.

That case remains in court although ACLU-NH, The Telegraph of Nashua, Newspapers of New England, Inc., Seacoast Newspapers, Inc., Keene Publishing Corporation, and the Union Leader Corp. have withdrawn saying they agree with the state that the new law makes the lawsuit unnecessary.

The lead plaintiff, the New Hampshire Center for Public Interest Journalism, wants the case to go forward.

The Center previously argued the new law strikes the wrong balance between the public’s right to know about the functioning of law enforcement officers and departments where serious misconduct allegations exist versus the privacy of individual officers.

The state has asked that the case be dismissed because of the new law and the Center will file its response next month.

Disclaimer: The New Hampshire Center for Public Interest Journalism is the lead plaintiff in the public records lawsuit.