By Stuart Silverstein

FairWarning

When the Republican-controlled Congress approved a landmark program in 2003 to help seniors buy prescription drugs, it slapped on an unusual restriction: The federal government was barred from negotiating cheaper prices for those medicines. Instead, the job of holding down costs was outsourced to the insurance companies delivering the subsidized new coverage, known as Medicare Part D.

The ban on government price bargaining, justified by supporters on free market grounds, has been derided by critics as a giant gift to the drug industry. Democratic lawmakers began introducing bills to free the government to use its vast purchasing power to negotiate better deals even before former President George W. Bush signed the Part D law, known as the Medicare Modernization Act.

All of those measures over the last 13 years have failed, almost always without ever even getting a hearing, much less being brought up for a vote. That’s happened even though surveys have shown broad public support for the idea. For example, a Kaiser Family Foundation poll found last year that 93 percent of Democrats, and 74 percent of Republicans, favor letting the government negotiate Part D prescription drug prices.

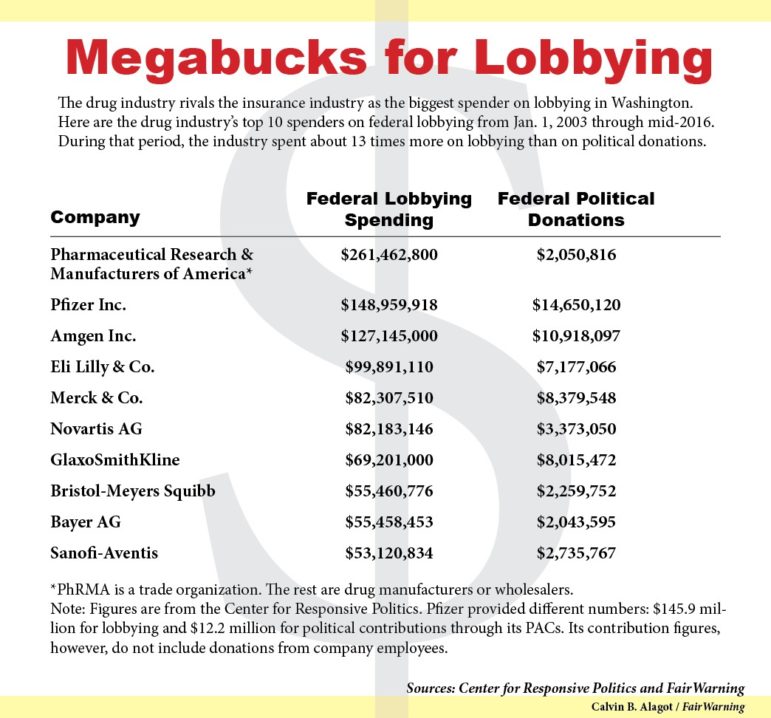

It seems an anomaly in a democracy that an idea that is immensely popular — and calculated to save money for seniors, people with disabilities and taxpayers — gets no traction. But critics say it’s no mystery, given the enormous financial influence of the drug industry, which rivals the insurance industry as the top-spending lobbying machine in Washington. It has funneled $1.96 billion into lobbying in the nation’s capital since the beginning of 2003 and, in just 2015 and the first half of 2016, it has spent $468,108 per member of Congress. The industry also is a major contributor to House and Senate campaigns.

It seems an anomaly in a democracy that an idea that is immensely popular — and calculated to save money for seniors, people with disabilities and taxpayers — gets no traction. But critics say it’s no mystery, given the enormous financial influence of the drug industry, which rivals the insurance industry as the top-spending lobbying machine in Washington. It has funneled $1.96 billion into lobbying in the nation’s capital since the beginning of 2003 and, in just 2015 and the first half of 2016, it has spent $468,108 per member of Congress. The industry also is a major contributor to House and Senate campaigns.

“It’s Exhibit A in how crony capitalism works,” said U.S. Rep. Peter Welch, a Vermont Democrat who has sponsored or co-sponsored at least six bills since 2007 to allow Part D drug price negotiations. “I mean,” he added, “how in the world can one explain that the government actually passed a law saying that you can’t negotiate prices? Well, campaign contributions and lobbying obviously had a big part in making that upside down outcome occur.”

Wendell Potter, co-author of a book about the influence of money in politics, “Nation on the Take,” likened the drug industry’s defiance of public opinion to the gun lobby’s success in fending off tougher federal firearms controls and the big banks’ ability to escape stronger regulation despite their role in the Great Recession.

“They are able to pretty much call the shots,” Potter said, referring to the drug industry along with its allies in the insurance industry. “It doesn’t matter what the public will is, or what public opinion polls are showing. As long as we have a system that enables industries, big corporations, to spend pretty much whatever it takes to influence the elections and public policy, we’re going to wind up with this situation.”

While Part D is only one of the issues the drug industry pushes in Washington, it is a blockbuster program. According to  “If you want to have lower prices, you’re going to have fewer medicines,” said Kirsten Axelsen, a vice president at Pfizer, a pharmaceutical giant that leads all drug companies in spending on lobbying and political campaigns at the federal level.

“If you want to have lower prices, you’re going to have fewer medicines,” said Kirsten Axelsen, a vice president at Pfizer, a pharmaceutical giant that leads all drug companies in spending on lobbying and political campaigns at the federal level.

It took intense maneuvering by the Bush White House and GOP leaders to get Part D through Congress in November 2003, when the House and the Senate were under Republican control. The measure came up for a vote in the House at 3 a.m. on the Saturday before Thanksgiving, as lawmakers were trying to finish business before the holiday. But when the bill appeared headed to a narrow defeat after the normal 15 minutes allowed for voting, Republican leaders kept the vote open for an extraordinary stretch of nearly three hours, described in a 2004 scholarly paper as by far the longest known roll-call vote in the history of the House.

With the help of pre-dawn phone calls from Bush and a custom-defying visit to the House floor by Tommy Thompson, then secretary of Health and Human Services, enough members were coaxed to switch their votes to pass the bill, 220-215, shortly before 6 a.m.

Part D was conceived at a time when rapidly rising U.S. drug costs were alarming seniors, prompting some to head to Canada and Mexico to buy medicines at dramatically lower prices. With the 2004 presidential election campaign coming up, Republican leaders saw “an opportunity to steal a longstanding issue from the Democrats,” said Thomas R. Oliver, a health policy expert at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the lead author of the 2004 paper about the adoption of Part D.

A key aim of Part D proponents, Oliver said, was to cover seniors “in a Republican, pro-market kind of way.” That meant including “as much private sector involvement as possible,” which led to insurance companies managing the program. At the same time, it excluded federal price controls, which were anathema to the drug industry.

Today, the program remains subject to the pervasive influence of the drug industry. An analysis by FairWarning, based on spending data provided by the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonprofit and nonpartisan research group, has found:

–There are far more lobbyists in Washington working for drug manufacturers and wholesalers than there are members of Congress. Last year the industry retained 894 lobbyists, to influence the 535 members of Congress, along with staffers and regulators. From 2007 through 2009, there were more than two drug industry lobbyists for every member of Congress.

–For each of the last 13 years, more than 60 percent of the industry’s drug lobbyists have been “revolvers” – that is, lobbyists who previously served in Congress or who worked as Congressional aides or in other government jobs. That raises suspicions that lawmakers and regulators will go easy on the industry to avoid jeopardizing their chances of landing lucrative lobbying work after they leave office.

Probably the most notorious example was the Louisiana Republican Billy Tauzin. He helped shape the Part D legislation while chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. In January 2005, just days after he retired from the House, he became the drug industry’s top lobbyist as president of the powerful trade group, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, or PhRMA. He remained in that job – which reportedly paid him $2 million a year — until 2010.

“It was pretty blatant but an accurate reflection of the way pharma plays the game, through campaign contributions and, in Billy’s case, way more than that,” said U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky, an Illinois Democrat who has been a leading proponent of government price negotiations.

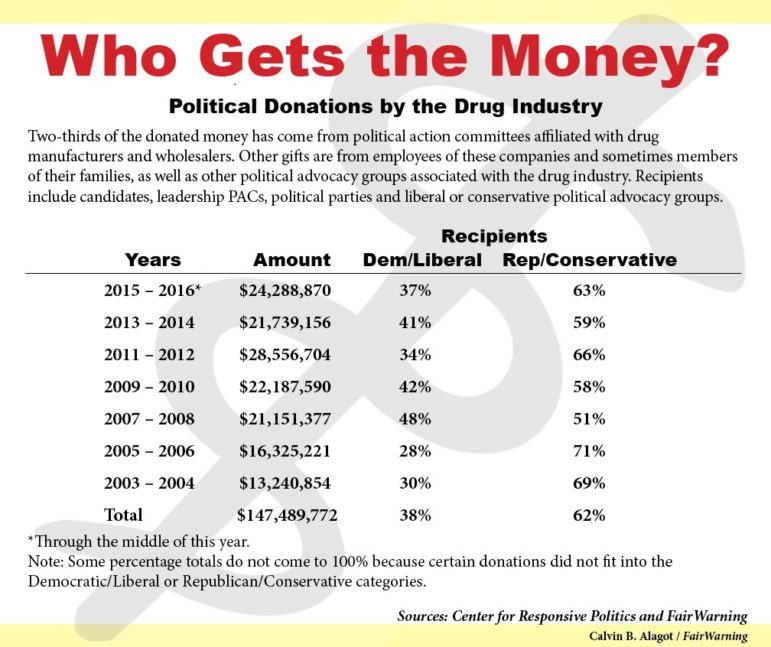

–Since January 2003, drug manufacturers and wholesalers have given $147.5 million in federal political contributions to presidential and Congressional candidates, party committees, leadership PACs and other political advocacy groups. Of the total, 62 percent has gone to Republican or conservative causes.

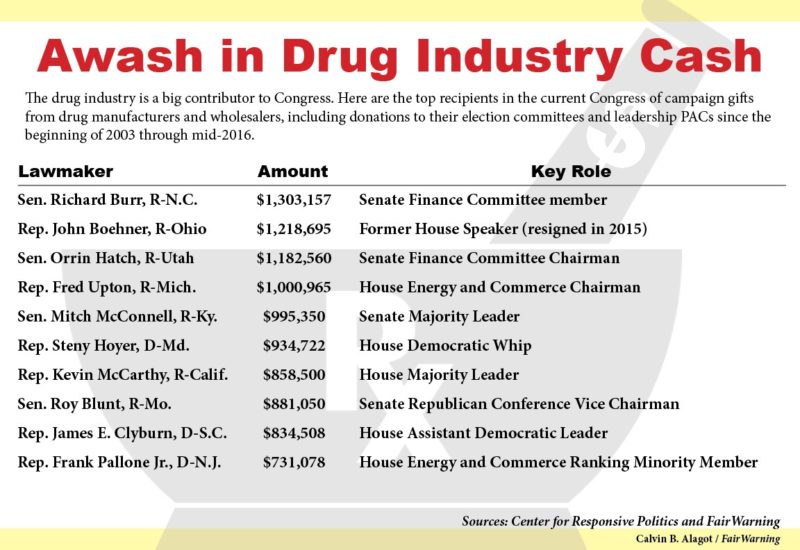

Over the period, four Republican lawmakers from the 2015-2016 Congress received more than $1 million in contributions from drug companies. (One of them, former House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, resigned last October.) In all, 518 members of the current Congress — every member of the Senate and more than 95 percent of the House – have received drug industry money since 2003.

Pfizer said since the beginning of 2003 through the middle of this year it has spent, at the federal level, $145.9 million on lobbying as well as $12.2 million on political contributions through its PACs. In a written statement, the company said: “Our political contributions are led by two guiding principles — preserve and further the incentives for innovation, and protect and expand access for the patients we serve.”

–The big money goes to top Congressional leaders as well as chairs and other members of key committees and subcommittees.

The House Energy and Commerce Health Subcommittee, repeatedly a graveyard for Part D price negotiation bills, underscores the pattern. The 16 Republican members received an average of $340,219 since the beginning of 2003.

The drug industry “knows that you really only need, in many cases, just a small number of influential members to do their bidding. That’s why you see contributions flowing to committee chairs, regardless of who is in power. They flow to Democrats as well as Republicans,” Potter said.

Proponents of negotiations say some economic and political currents may turn the tide in their favor. The main factor: After years of relatively modest price increases for prescription drugs, cost increases have begun to escalate. That’s partly due to expensive new treatments for illnesses such as hepatitis C.

According to Medicare officials, Part D payments are expected to rise 6 percent annually over the coming decade per enrollee, up from only 2.5 percent annually over the last nine years. Already, cost increases are “putting wicked pressure on our hospitals, on our seniors and on our state governments,” Welch said.

At the same time, both major presidential candidates, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, have called for Medicare drug price negotiation. So have doctor groups such as the American College of Physicians and an alliance of more than 100 oncologists, many nationally known, who last year garnered headlines with their plea for Medicare negotiations and other measures to fight skyrocketing costs for cancer drugs.

PhRMA, the trade group, wouldn’t comment for this story on lobbying or campaign spending.

In a written statement, however, PhRMA spokeswoman Allyson Funk said, “There is significant price negotiation that already occurs within the Medicare prescription drug program.” Pointing to the private companies that run the program, Funk added, “Large, powerful purchasers negotiate discounts and rebates directly with manufacturers, saving money for both beneficiaries and taxpayers.”

Funk also pointed to skeptical assessments by the Congressional Budget Office about the potential additional savings from federal negotiations. Repeatedly – including letters in 2004 and 2007 – the CBO has said government officials likely could extract only modest savings, at best. The office’s reasoning is that costs already would be held down by bargaining pressure from insurance firms and by drug manufacturers’ fear of bad publicity if they are viewed as jacking up prices too high.

But many analysts, particularly amid recent controversies over skyrocketing costs for essential drugs and EpiPen injection devices, scoff at those CBO conclusions. They fault the CBO for not taking into account other price controls, such as those used by Medicaid and the VHA that likely would be coupled with price negotiation.

What CBO officials “seem to be assuming is that Congress would change the law in a really foolish way,” said Dean Baker, a liberal think tank economist who has studied the Part D program. “It seems to me that if you got Congress to change the law, you would want Medicare to have the option to say, ‘OK, this is our price, and you’re going to take it. And if you don’t take it, we’re not buying it.”

In fact, related bills proposed during the current Congress by two Illinois Democrats – Schakowsky and Richard J. Durbin, the Senate minority whip — go beyond requiring drug price negotiations. They both provide for federal officials to adopt “strategies similar to those used by other federal purchasers of prescription drugs, and other strategies … to reduce the purchase cost of covered part D drugs.”

The potential to reduce prices is underscored by a 2015 paper by Carleton University of Ottawa, Canada, and the U.S. advocacy group Public Citizen. It found that Medicare Part D on average pays 73 percent more than Medicaid and 80 percent more than the VHA, for the same brand-name drugs. The VHA’s success in holding down costs helped inspire a measure on California’s November ballot, Proposition 61, that would restrict most state-run health programs from paying any more for prescription drugs than the veterans agency does.

Two studies by the inspector general of Health and Human Services that compared drug expenditures under the Part D and Medicaid programs also concluded that Part D pays far more for the same medicines. The more recent inspector general study, released in April 2015, examined spending and rebates on 200 brand-name drugs. It found that, after taking rebates into account, Medicaid, which provides health care for low-income families with children, paid less than half of what Part D did for 110 of the drugs. Part D, on the other hand, paid less than Medicaid for only five of 200 drugs.

Those findings provide evidence that “the current reliance on private insurers that negotiate drug prices isn’t working that well,” said Edwin Park, vice president for health policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington think tank.

Five Democrats who are leading opponents of the status quo – U.S. Representatives Welch, Schakowsky and Elijah E. Cummings of Maryland, along with Senators Durbin and Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota — each have introduced price negotiation bills (H.R. 3061, H.R. 3261, H.R. 3513, S.31 and S.1884) during the current, 114th Congress. All of the measures have stalled in committee.

Schakowsky, a House Democratic chief deputy whip, said under Republican control in her chamber, “I think it is virtually impossible for this to ever go to hearings and markups.”

Take, for example, the bill that Welch introduced in the House on July 14, 2015. Within a week, it was referred to two health subcommittees, where it has sat ever since.

The closest Welch ever came to success was in 2007. He was among 198 co-sponsors – all but one, Democrats – of a bill introduced by then-U.S. Rep. John D. Dingell of Michigan. It was approved by the House but then blocked by Republicans from being taken up in the Senate.

Lawmakers on committees where Part D bills ordinarily go – Finance in the Senate, and Energy and Commerce as well as Ways and Means in the House – tend to be well-funded by the drug industry.

For instance, Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C., who sits on the Finance Committee, has received more money from the industry since 2003 than anyone else currently in Congress, $1,303,157. Close behind is Senate Finance Chairman Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, who has gotten $1,182,560. (The other members of the million-dollar club are Rep. Fred Upton, R-Mich., the House Energy and Commerce chairman, at $1,000,965, and former House Speaker Boehner, at $1,218,695.)

Burr also is the Senate leader so far in the 2015-2016 political cycle, collecting $229,710 from the drug industry. In the House in the current cycle, John Shimkus, R-Ill., a member of the Energy and Commerce health subcommittee, has snagged $189,000, trailing only Republican Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy ($292,550) and House Speaker Paul Ryan ($273,195).

A Burr spokeswoman declined to comment. Hatch and Shimkus failed to respond to repeated requests for comment.

Amid the EpiPen controversy and growing concerns about prescription drug prices, Park sees signs that more lawmakers are willing to buck industry opposition to government price negotiation.

“There’s a lot of industry opposition. This would affect their bottom line,” Park said. “It doesn’t mean, however, that industry is all-powerful.”

But Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, was skeptical about the prospects for reform. “I think it’s pretty clear what you’re seeing is, there’s an industry group that stands to lose a lot of money, and they’re basically using all of the political power they can to make sure that it doesn’t happen.”

##

This story was reported by FairWarning (www.fairwarning.org), a nonprofit news organization based in Pasadena, Calif., focusing on public health, safety and environmental issues. Deborah Schoch, a freelance health and science writer, and Douglas H. Weber, a senior researcher for the Center for Responsive Politics, contributed to this story.