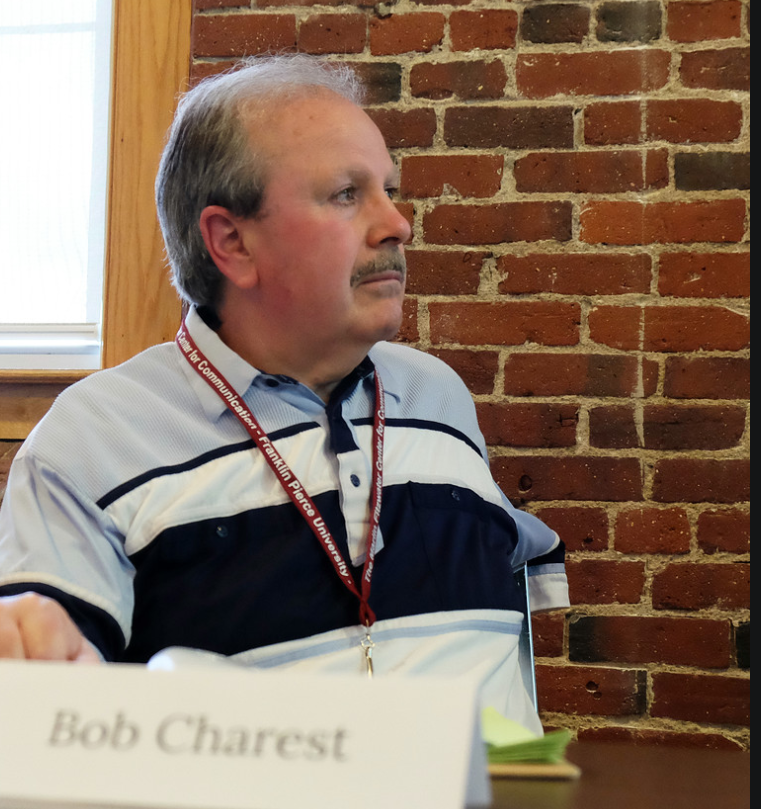

By BOB CHAREST, Why You Should Care New Hampshire

I’ve been to so many Zoom meetings in the past few weeks that I’ve seen more nostrils than a dental hygienist. People, you have to aim those laptop cameras carefully.

When I had a chance to attend a webinar on the crisis in journalism, a discussion facilitated by the Columbia Journalism Review and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, I hesitated. After all, journalists are pretty lax in trimming their nose hairs.

And we all know about the generally dismal situation with newspapers. Did I want to hear about it beyond what I’ve already read ad nauseum? You just have to pick up a copy of the New Hampshire Union Leader, which on a recent weekday contained 20 pages. There’s barely any advertising inside, and the Sunday News rarely contains a department store insert lately. They’re trying something new over there, a matching grant-type deal in which advertisers basically get their ads for half-price. It’s an example of how newspapers have to think creatively these days.

To call the situation dire is something of an understatement. I tuned in to the webinar, and I heard the experts speak. We have to do something, they said. We can’t let newspapers go away, they said.

It seems that everyone, including newspapers that always made their money in other ways – namely subscriptions and advertising – have their hands out looking for donations these days.

That’s why, when you look anywhere on the Internet at a newspaper website or even on Facebook, you’ll probably see a pitch for a donation to help the “legacy media,” as newspapers have been so named in the online media world. This is making the whole field of fundraising for journalism a tad bit overcrowded.

After all, if people weren’t paying for it before the pandemic, what makes any of us think they’d be willing to pay for it now? Therein lies the problem, and it’s time for everyone to put on their thinking caps.

There are some who say the current crisis will accelerate the demise of newspapers. Some newspapers in New Hampshire have already taken to curtailing their print production by eliminating a print product on some days. One, the Nashua Telegraph, is online seven days a week, with only a Sunday edition printed on Saturday. Layoffs and furloughs are the order of the day. My Facebook feed just today produced a post from a friend in the newspaper business who was laid off Friday.

So I ask you: Should we save newspapers?

If this were a brush fire, would you let it burn, as has been suggested by a recent piece in the New York Times?

That article was railing against the big media conglomerates, some of which are owned by hedge funds and private equity firms that raided the assets of the newspapers it buys, making some of the latest big deals not worth the fire-sale prices.

That article makes the case that it’s now time to abandon most for-profit local newspapers, with failing business models, and instead create online newsrooms. Instead of rescuing the gutted newspapers, we instead rescue the journalists.

While you have your chance personally to answer the call and donate some of your own money, have you, or will you? There are also moves afoot in Congress to help rescue journalism. I ask you: Is that a good idea for government to get involved in supporting government watchdogs?

Historically, with most products and goods available to consumers, the market decides. And when the market isn’t there anymore for your product, you and your company cease to exist. The problem with this is that journalists tend to pick up a pen and not a box of tissues if something ails them. If you thought a newspaper reporter was going to go away quietly, no way: They will not go gently into the good night. That’s why wherever I turn on the internet, there’s always another essay about why we need newspapers and how democracy will suffer, so on and so forth. (The deluge is probably related to the fact that I belong to several email groups and Facebook groups devoted to the industry.)

But there is a further problem with this survival-of-the-fittest, market economy narrative: Newspapers are not your typical consumer product. They don’t equate with VHS players and eight-tracks and drive-in theaters and other things that have largely gone away.

Newspapers have a value that goes much, much deeper than a typical consumable good. (I worked in newspapers for 33 years. Did you think I was going to say anything other than that?)

That’s why this webinar I attended hit home.

One of the participants, Penny Abernathy, Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said this: “There’s both the loss of newspapers and that has tended to happen among very small weeklies and dailies, and they have often gone unnoticed because it doesn’t really make headlines outside of the communities that they serve. And then there’s the loss of journalists, and that has tended to hit the state and regional newspapers much more than it has hit the smaller newspapers. And we have a loss of news in both ways. We lose routine government coverage that brings transparency at the local level and connects us with our local institutions, and then when we lose the investigative reporters, the beat reporters on a state and regional newspaper, we lose something else.”

So I ask: Should we forget the newspapers and save the journalists?

That’s been one of the points under debate. Maybe it’s time we moved to an online world (like we are doing here at InDepthNH.org). But a word of advice: This is not easy. For the past five years, I’ve been a witness to the struggle getting such an operation going and growing. It’s due to the sheer grit and determination of founder Nancy West that it still survives.

In a May 2017 survey published on the statista.com website, 30 percent of those surveyed between the ages of 18 and 29 never read a newspaper, and in that same age group, 26 percent read a print newspaper less than once a month. In fact, only 6 percent of those age 18 to 29 report reading a newspaper daily, compared with 15 percent of those age 30 to 59, and 23 percent of those age 60 and older.

We used to say in the newspaper business that we have a special page for our loyal readers every day. It’s called the obituary page.

Are newspapers not giving readers what they want? There’s an argument to be made. I’ve witnessed in my lifetime the disappearance of birth announcements, and I rarely see an engagement or wedding announcement anymore. It seems to me this is the content that would appeal to younger readers. And what Little League player or high school athlete doesn’t want to see his name in the paper? Of course, we are living in Covid-19 times, but I don’t know that a lot of newspapers even have the staff anymore to take dictation from a coach calling in his stats after a game, never mind sending a reporter to cover many of them.

I do from time to time meet a twentysomething here and there. I can’t say that any of them have ever told me of something they’ve read in a newspaper. On Facebook, yes. In the Boston Globe, never.

I came of age in the business when it was fashionable for three correspondents to be sitting in the audience at small-town selectmen, school board and planning board meetings. I’d get some good stories out of those meetings, which I’d have to type up after midnight and deliver early the next day to the office. I’d do those stories on an IBM Selectric while I still lived at home and had to put the thing in the middle of the bed so the clatter wouldn’t wake up everybody in the house.

I had to hustle because if I didn’t have the story the next day, with three or four other newspapers covering the same town, I could have been beaten. And no one wants old news. There’s only so many ways to write a second-day lead on a story.

But now we have something called “news deserts.” These are places where no news coverage exists.

As Abernathy pointed out in the webinar, “The places that are most likely to have lost a newspaper and not have any alternative news outlet that’s covering them happen to be the ones that are really on the margins. They tend to be economically struggling, much poorer communities. They also tend to be heavily minority or ethnic communities. I live in a news desert. I live in one of the poorest counties in North Carolina.”

Abernathy says the ramifications of this are fairly serious. Not only are these people already marginalized, they face problems with lack of communication and representation. Abernathy says in her county, a recent Covid-19 map projecting future cases showed the potential for a major outbreak right there in her county. How would those residents know or prepare?

Another participant in that webinar, Sarah Stonbely, research director at the Center for Cooperative Media at Montclair State University in New Jersey, said this: “Local journalists have to do a much better job of publicizing themselves and asking for money. It is so not in the DNA of legacy journalists who are in big traditional newsrooms, and it’s something people are willing to pay for now. I don’t think everyone thinks all content on the web is free anymore. I think it’s something people are willing to pay for.”

That last statement, I’m not so sure about. Prove me wrong.

Are newspapers going the way of my old IBM Selectric? God, I hope not.

Bob Charest hates to admit it, but he’s been in the news business since 1977. He now serves as secretary of the board of the New Hampshire Center for Public Interest Journalism, the parent organization of InDepthNH.org.