The most recent Laurie List of dishonest cops can be seen here: https://indepthnh.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/November-5-2024-EES-List.pdf

Read more of our coverage here: https://indepthnh.org/category/dishonest-police/

By DAMIEN FISHER, InDepthNH.org

A retired Hanover police officer who forged a doctor’s note for extra pay is now likely to get taken off the Exculpatory Evidence Schedule, also known as the Laurie List, thanks to the New Hampshire Supreme Court.

In a case order issued Wednesday, the justices unanimously state that the forgery incident is too far in the past to be relevant to any pending criminal cases. Citing their recent ruling in favor of three New Hampshire State Police Troopers who were disciplined for faking activity logs more than 20 years ago, the justices state the age of police misconduct needs to be factored into EES decisions.

“If there is no reasonably foreseeable case in which ‘potentially exculpatory evidence’ relating to an officer’s conduct would be admissible, due to the passage of a significant length of time or some other factor weighing on the conduct’s relevance,’ an officer’s inclusion on the EES would not be warranted,” the justices state.

The officer brought the complaint as a John Doe plaintiff to argue he should not be on the EES for something that happened more than 20 years ago. According to the case order ruling, Doe forged his doctor’s signature on a medical clearance form in order to qualify for a stipend the department paid to officers who could pass a physical agility test.

Unfortunately for Doe, he shared a doctor with at least one other police officer in the department. An internal investigation into Doe kicked off when a department secretary noticed the signature on Doe’s form did not match the signature on the other officer’s form.

Doe would subsequently admit to the investigators that he forged the signature, and the then-chief sustained the finding that Doe lied to the department. He was suspended for two weeks, but not placed on the EES at that time.

Several years later, before he retired, Doe was able to have his disciplinary record cleared from his file thanks to the union’s collective bargaining agreement with the town. But after he retired, Doe was informed he was getting placed on the EES.

After Doe brought his lawsuit, Superior Court Judge Lawrence MacLeod sided with Hanover and the New Hampshire Attorney General’s Office in keeping Doe on the EES. MacLeod ruled that a defendant facing criminal charges in a case where Doe would be a witness had a right to know about the forgery.

‘[F]orging a signature in order to secure a stipend is probative of the plaintiff’s character for truthfulness or untruthfulness, which may be inquired into on cross-examination, because it shows that he has lied,” MacLeod said.

But the Supreme Court Justices ruled that because the forgery took place more than 20 years ago, and Doe is currently retired, he is unlikely to be called as a witness in any criminal case. In September, a divided Supreme Court ruled that the state should not put three John Doe troopers who created bogus activity logs to show they were doing more police work than they were in reality.

Like the Hanover Doe, the Doe troopers were disciplined for the bogus reports more than 20 years ago. And like the Hanover Doe, they all went on to have clean discipline records for the rest of their careers.

Chief Justice Gordon MacDonald was the lone dissent on the September opinion.

“I am unaware of any legal basis to impose an expiration date on the potentially exculpatory fact that, for instance, an officer lied,” MacDonald wrote.

But, MacDonald signed onto this week’s case order ruling along with the other justices. The September opinion on the three Doe troopers set legal precedent which the Court applied in this Hanover Doe case order. Case orders do not carry precedential weight.

The law enforcement officers were allowed to challenge their placement on the list before their names would be made public because of a law passed in 2021.

The officers on the list then were notified of their option to argue in Superior Court to have their names removed and some of the cases remain in court three years later with most having filed confidentially under Jane or John Joe.

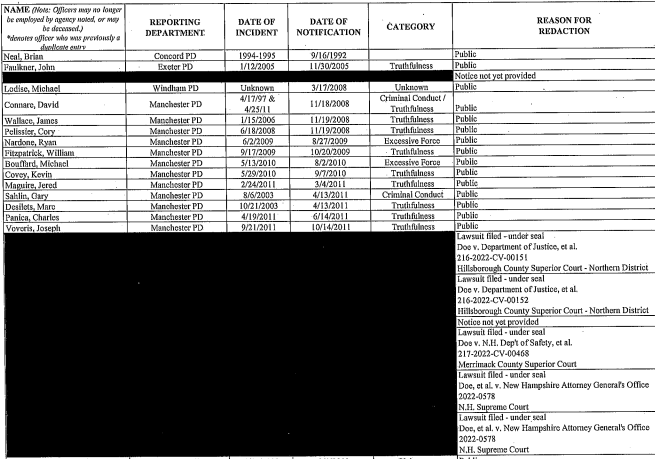

There are presently 270 officers on the exculpatory evidence schedule.

The names of 222 have been disclosed to the public; 75 officers have notified the Department of Justice that they have filed lawsuits. As of the date of this report Nov. 5, 2024, there are 59 pending lawsuits.

Those who haven’t yet been notified of the 2021 law and their options to keep their names secret are either deceased, on military deployment overseas, or the Attorney General has been unable to obtain any contact information for the individual from the relevant law enforcement agency that last employed the individual or the Police Standards and Training Council. “This Office is actively addressing these situations,” and has been since the new law was passed.

Under the terms of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brady v. Maryland case more than 50 years ago, the names of officers with sustained discipline for credibility problems or excessive force issues in their confidential personnel file must be disclosed to defense attorneys before trial, but their identities would otherwise be kept hidden from the public.

Prosecutors must provide such evidence about sustained police discipline to criminal defendants if it is considered exculpatory, or favorable to the defendant involving dishonesty, excessive force or mental illness.

Criminal defendants who find out later that such police discipline was withheld before trial can argue in court to try and get a new trial or have their case dismissed in egregious cases.

To date, the state has taken no action to alert defendants who were not told of the secret police discipline that would allow them to challenge their convictions based on the state withholding evidence in their favor when the names of the officers with credibility issues have become public since the new law went into effect three years ago.