Monadnock Region: Henry Walters is many things. He is an award-winning poet and Master Falconer, who at one point in his life climbed Pack Monadnock every day for three months to count birds of prey as they flew over. The book we are exploring is Field Guide A Tempo, part of The Hobblebush Granite State Poetry Series 2014. He is a kind and soft-spoken fellow. I discovered Henry when I dropped by my local library and a crowd had formed awaiting Henry and his birds of prey for a free, live public appearance. He works at Monadnock Falconry which is committed to raptor-related environmental education throughout New England. His newest book, The Nature Thief, was a finalist for the Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize.

Field Guide A Tempo explores his deeply interesting and self-revealing poetry that discloses his beautiful mind showing us his love of nature, birds, and music. Chapters in the book are Italian musical terms: Da Capo (From the Beginning), Animato (An Animated or Lively Quality), and Coda (The Tail or Concluding Section). It is here we should add Henry has studied Latin and Greek at Harvard College, moved to Sicily for a half year and learned beekeeping, and studied his current profession of falconry in Ireland. There is music in his words, and I asked him where the music comes from. Please note this interview has been edited for length and clarity.

“I play the piano, and have since I was a kid, and a little bit of the harmonica. As for so many people, my love of art oftentimes starts in music. It’s something about the music of a poet’s lines that makes me want to know the poems and walk around with the poems and sometimes imitate the poems. All our poetry, both folk traditions and more literary traditions do have their roots in something sung. In Homer and Beowulf and the Anglo-Saxon tradition or our folk traditions of ballads of troubadours in France and England in the late Middle Ages, music is at the heart of poems, and the language has come along for the ride. It’s hard to sit down with a chunk of text in front of you and hear it as a musical thing. But that’s always been my hope in reading and in writing.”

I explained to him that I needed to read a poem out loud. You really can’t just keep it inside. You can internalize it, but you have to give it back somehow. It’s like a stress relief when you breathe deep breaths in and you breathe out the words, the language.

“I couldn’t agree more, there’s something bodily about it. The body has to participate in it, right? If poetry’s going to energize and enliven, the limbs have to be involved, and the breath and the heartbeat. That’s the reason particular forms of poetry have endured, particular rhythms keep recurring. They’ve got a lot to do with our footsteps. They’ve got a lot to do with our heartbeat. Even if the poems themselves can cruise off into abstraction there, I do think the body has a role to play.”

Henry suggested we explore four of the poems that were his favorites, and I found that I loved each one of them as well. We started with Presto which means in Italian very fast, and it is written as one long sentence which hastens you as the reader. Then if you read it out loud, it’s, “Let’s play for real this time. I mean it, no matter what the first one to speak is in and after that, it’s the thing you say it, that’s it.” The way the poem is written, you’ve got to punch it, punch it, punch it. Is that what you intended?

“I was imagining partly the music of how kids talk, which is oftentimes unpunctuated and very quick. One thought follows immediately after the next, so that, for one thing, it makes it difficult to tell which part of that one long and broken sentence is the most important, right? You just go, go, go. There’s beauty in watching a child speak and those connections being made as they talk. That particular music is what I was after.”

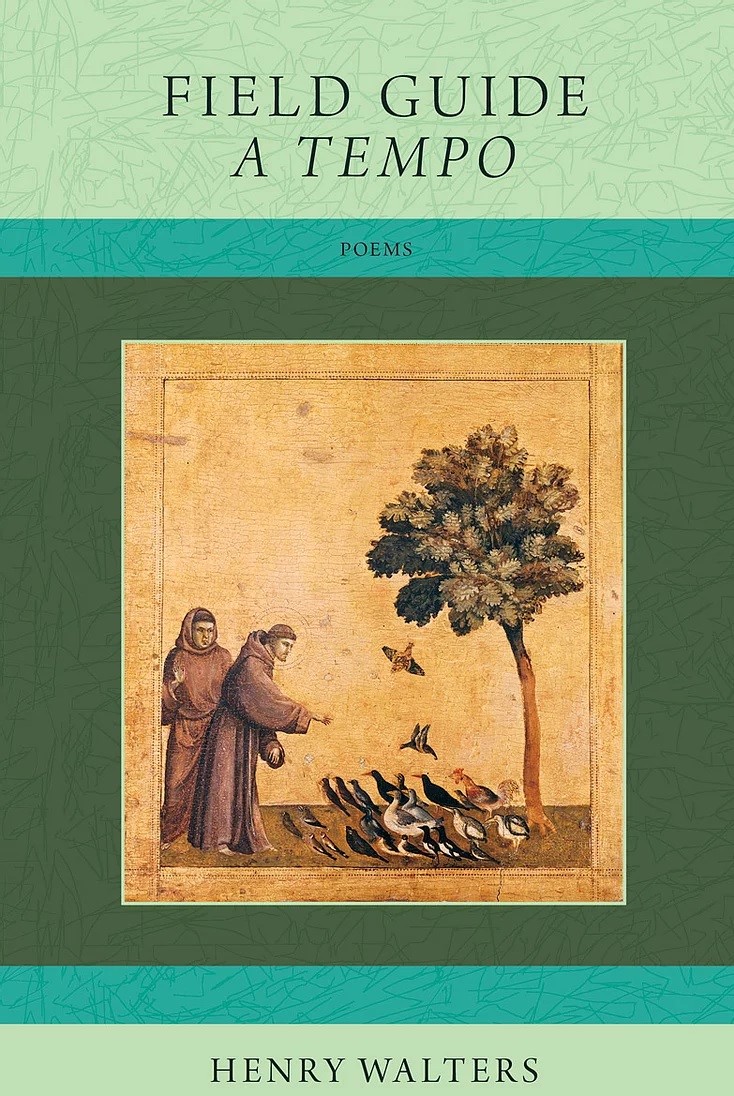

The book is beautifully designed and published by Hobblebush Books, Concord, NH, and is a part of their Hobblebush Granite State Poetry Series, Books by New Hampshire authors for any state you’re in. On their website, they write, “We are in a unique position to produce beautiful volumes of some of New Hampshire’s best poets.” The editors are listed as Sidney Hall, Jr, and Rodger Martin.

“The founding editor of the press is a wonderful man named Sid Hall, who’s a poet himself. He’s a really interesting guy, both for his own work and what he’s done to support poets in New Hampshire. I had read a book by another poet, Jim Kates, which came out in the series, and liked it so much, both the book itself and the design of it, they were the first press to which I sent this manuscript, and they did right by it. It’s a very crowded world of poetry presses and poetry books. And to give that time and attention the way they did meant a great deal.”

“Sid Hall and Roger Martin, who’s another editor with the series probably could tell you more about its history. I think they were channeling this long and rich tradition of poetry in New Hampshire that goes back to May Sarton and Robert Frost. There was a tradition of people writing poetry, especially poetry connected to the land and the natural world, and somebody needed to put banks around the current of that tradition. The other poets who have published in this series are some of them very well-known and I think they’ve chosen wisely. It hasn’t thinned out over time.

Let’s go on to Lookout. The last stanza reads, “And then, September hawks lift off from those hills,/All aimed in one direction, passing through/Without password, without permission, their fanned tails/Flying colors you’ve never paid attention to/Till now, beautiful, barbarian syllables,/A whole sky, unopposed, invading you.” The title is, Lookout, like a sentry but it could be read quickly – look out – a warning. What were you thinking when you wrote this poem?

“I love that interpretation. It is sort of a call to action, a call to look up. And this ties in very much with my interest in birds and hawks in particular. But what first drew me to New Hampshire was taking a job with New Hampshire Audubon, counting migratory birds. I knew this migration went on, of course, all across North America, but the job got to me. You’re stationed on a northward-looking mountain for really, every day of September, October, and November, watching, watching the north, and trying to count what comes by and identify what comes by, trying to get a sense of bird populations. And many of those hours, you’re not seeing anything, you’re just looking, looking to the north, hoping to spot some spec. Then that spec grows and becomes an identifiable thing with wings, and you jot it down. And some of those days, you’re seeing 5000 birds in a day, just sort of coming out of the woodwork, coming out of nowhere, and going all the way down to Brazil. It was a really special experience to be stationed there, and as you’re standing up there, you do feel a little bit like not a guard, exactly, but thinking back to other lookouts, in the sense of people looking out both, you know, fire wardens manning a fire tower, or soldiers, or people trying to give messages from one mountain top to another. And because I was the one whose job it was to pay attention to this particular thing, that you feel like you are the boundary, that you’re standing at the boundary. But even though it’s woods to the north and woods to the south, you still feel like you are the one that is opening the door to this flood of migration, and also you see very clearly that the birds don’t care for your boundaries. They don’t see you as a boundary. They don’t even pay any attention to you at all. They’re just passing by. All our worries about boundaries and borders, who can stand where on whose land. It puts that into perspective so that our human concerns all of a sudden seem quite small. And I guess that’s why I’m framing it in these military terms, about enemy lines, and a sky unopposed and invasion, that a person, as well as a place, can feel invaded by other forces, and that invasion can be wonderful. It’s great to be taken out of yourself even for a moment and be part of the sky or part of this migration. You’re standing there in place. You’re not moving, but you are a part of it. That’s how I felt up there and how that’s the kind of invading that I want poems to do, too: they give us the chance to be taken over by another point of view.”

You were looking for all kinds of birds, though, right, specifically, or was it?

“Specifically birds of prey, just because they’re real indicators of how the ecosystem is doing as a whole. So if you’re not seeing so many birds of prey, well, there’s something else going on in the ecosystem, but, I was counting all birds, including songbirds, but most songbirds, are migrating by night. Some of them aren’t able to survive our winters. They’re feeding on rodents that are under the snow, in other cases the density of those birds in the summertime would be too great to catch enough food to raise young. So they sort of have to spread out in the summer. If they want territories big enough to be able to feed their chicks, they need to have larger territory, so that’s the reason to migrate.”

And what did you discover in those three months about the health of the ecology?

“Well, it’s a long-term thing, like you see different numbers of birds each year depending on the particular weather on particular days. But if you continue that study long enough, you begin to see those trends emerge, and they’re finding some amazing things. It was hawk watches that pointed out we had a problem with DDT, this pesticide we thought was fairly safe, in fact, was making all these animal populations crash, and we didn’t know that until we surveyed birds of prey and found that we were seeing fewer and fewer peregrine falcons and bald eagles, and ospreys each year. We’re seeing something of the same thing with kestrels in the east, a real plummeting of that population, not understanding why yet. But other populations are doing okay.”

The next poem, “Milkman” is in the Tempo Mortale section. Mortale, something like death and dying? Where did that poem come from?

“I lived for a while in a cabin on Willard Pond just outside the town of Hancock, but it was a very mouse-ridden cabin on the edge of this pond, a beautiful spot, but felt quite remote. And, in the winter, I just had the mice for company for long stretches of time, a week or two at a time, and also the voices of musicians I would listen to.”

“One of them is this blues singer, Son House.” (Eddie “Son” House is a Delta Blues singer and guitarist.) Just thinking about people who are looking for communication from the outside, right? This is a sad song about getting a letter about somebody who’s died, and the way it comes on my record is that it will skip at exactly that point. (Henry sings this.) So got a letter this morning, got a letter this morning. And, you know the feeling of having a skipping record, it seems to be it’s just an accident, but it also feels like it’s telling you a message, and just thinking it, along with listening to that and feeling quite isolated in my cabin, trying to get into the mindset of other people who have been looking for messages, who have been looking for arrivals.”

“And that prompts this image of the milkman arriving at your doorstep each morning, bringing you something essential that also must have felt like just manna from heaven to wake up and be in your robe and open the door and find fresh milk there. Where now we feel like we’ve got to preserve it. It’s got to be in our fridge. Not till then did I think about the milkman, a real man to my parent’s generation, but myth to mine, who’d come in the dawn and leave two bottles on the stoop beside the door uncapped, they said, and frothy and sometimes warm, narrow-necked bottles that flared out like the bell of a gramophone, as if the bottles themselves were a kind of record player that was trying to tell you something, trying to sing you something trying to be a message from another place. But now your bottle floats up into mind, milkman, minstrel, waylaid, a messenger without a message without milk, without even a sun to slip slow through your glass and you say hush. I thought I heard her call my name. Those are lines from that same song with which we began, and suddenly you’re being gone, delivers me a second time into the world.”

“So I think oftentimes the moment that a poem starts is the moment that your mind is in one place, listening to one thing, thinking about another, thinking about one particular thing, and in the middle of that unbidden without really seeing a cause, another pressing, even more important, idea or thought or feeling wells up from within it, and you’re not necessarily sure about what connects the two things, but the fact that one thing gives rise to the other makes you want to track that. How did I get from listening to this song on a skipping record, to feeling hungry, to thinking about a milkman to thinking about the death of somebody that I loved and wanted a message from even if, I mean, in this case, it’s my grandmother, in a way that’s not important. I didn’t have to call the poem thinking about my grandmother, but how the mind gets there and how you almost have to work in a bodily way, working through these different thoughts, to get to the point where to get to the really important thing. I think that’s one thing poems are good for.”

Why were you all alone in this cabin with just mice for company and your gramophone? What were you doing there?

“Writing for one thing, reading and writing, playing the piano. This was a cabin owned by New Hampshire Audubon. It had been empty. They were looking for a caretaker, both for the cabin and for the piece of conservation land that surrounds it. It was going to be free rent, and I needed a place to stay. So, that’s why I took it. And it remains one of the dearest places, although it was lonely from time to time.”

I can see how it would be. You start that poem with “Not till this old-fashioned morning, Son House singing/through fifty pushups, fifty situps, some pain-/ful stretches into lower registers.” Was that true every morning?

“Yeah, you’d have to, especially in the cold. You got to get yourself moving a little bit while the stove warms up. There was electricity, but it was just heated with a wood stove, so it would take a while to warm up.”

We get to Promissory in the Coda section or conclusion. What is a red eft?

“A red eft is a very small salamander. You see them out walking. Sometimes they’re sort of bright orange, actually, more orange than red. Some of them are less than an inch big, and others are more than three or four inches. Sometimes they get caught out with the late snow in the early spring, and you see this bright orange thing against the snow. They have incredibly small, delicate toes and feet. They look like a very alien species.”

“This poem’s hard to talk about because it comes from somewhere that’s almost before or without language. In the way that sometimes you wake up in the morning and you know you’ve dreamed and something about the dream remains, but you can’t fix any images about it. You can’t even really say clearly how you felt about the images. It’s just like the whole state sort of hangs in the air, and it’s very difficult to say anything about it. And I guess that’s the feeling of, what more is there to say?”

“The poem begins in March. At the end of winter, all last year’s growth is smashed down by the snow, and you’re walking on top of it, so the ferns that were up to here on your walk last year now are underfoot, and all the things that you felt and dreamed and wanted to do last year, they are now past or under your feet.”

“A few fronds pressed/in winter’s book.” As if winter was a book that you could press a flower in. What more is there/to say? I still/say loves a sight/in a silent place.” For a poet, there’s the dream of finding an image that sums something up that pulls you together, whether with the hawk or a milkman or with the child with which we began. You’re in search of an image that can pull you closer to that person or thing, and here you don’t get it; instead, you have a promissory note saying IOU, saying a poet owes you something.”

“There’s a you at the end of the poem. Oftentimes, poems are tricky, until you figure out who is I and who is you. And here, “you” is not some far-off particular person, but you the reader, whoever is picking up this book, it’s a book that looks very much like winter. The pages are white, and there are a few images pressed into the book. I’m speaking directly to the reader there. “If I but knew/your name or where/to meet you, plain/as day, I’d press/the lettering/as small in snow/as a red eft’s print.” To me, that’s the right proportion. The poet and the poem are very, very small things. They’re very weak things. A little bit of winter is enough to destroy them. Most of them go unnoticed entirely, and that’s okay, but if they have some beauty to offer, just as the red eft has some beauty to offer, it comes at that moment of noticing it, and it’s very small and personal and intimate. I’m trying to end with that, that reminder to the reader about our relationship, that even though I don’t know who you are, I don’t know your name, and I might be dead by the time that you read this thing. However, the impulse and the love with which one writes still can come across, no matter what separates writer and reader.”

That’s just so wonderful. The poetry I read is only for me. It’s not for anybody else I’m going to share it with, on occasion I will, but it means something to me. And some of the lines you write are lines you will always remember.

“I hope that’s true.”

You grew up in Indiana and Southern Michigan, but it says you studied Latin and Greek at Harvard College. We’ll start with that before we go into the beekeeping, you went to Harvard.

“I did. I loved Greek myths as a kid, and especially the stories of these ancient worlds. So many kids are fascinated by the past in that way, by archeology, by the idea of lost civilizations and cultures. But it was the language that became very exciting to me. I studied those on my own and through correspondence courses until late in high school, where I found a teacher who is still very close to me, a professor at the University of Michigan. And that made me feel like these languages and the literature that use them are as rich as anything we’ve made as people, and that they were worth studying. I knew sort of from the beginning, that I wasn’t going to become a professor of classics, but I don’t regret spending all those hours hunched over dictionaries. Not only our own language is informed by exactly those languages, but our literature too, in ways that are always surprising and make you feel like those languages and cultures aren’t as dead as we sometimes make out.”

What took you to Sicily?

“After college, I had a fellowship to work in Ireland at a school of falconry. That’s where I began working in a hands-on way with birds of prey. I spent two years there and from there. Afterward, I ended up in Sicily with a family who was raising barn owls, but their main job was keeping bees and making honey and talking about the process of beekeeping to local people, and I stayed with them. At first, it was just going to be a week, and then it was six months, and then it was a year that I stayed with this wonderful family and helped them with their bees, and also did some translation work for them from Italian helping give presentations about the bees in English to people who would come by. It’s just a wonderful, marvelous family. I felt the richness of the modern language for the first time. Being plunged into those languages – Italian and Sicilian – and having to scramble to keep up was fun.”

Do you still keep bees?

“I kept bees until two years ago when they didn’t make it through the winter. It’s a hard state to be a beekeeper, but I will resurrect my hives again, hopefully next year. I’m newly a father, which is a wonderful thing, but that’s taken precedence over beekeeping this summer.”

You have an Irish accent. Did you pick that up by going to Ireland?

“You’re definitely not the first person to say. I think something of it must have rubbed off and stayed with me. I can’t hear it myself, but probably a couple of years in Ireland made that happen.”

So where did the bird interest come in when you were a young kid?

“I think so. Birds have just been such a rich and maybe the richest symbol of sort of the poetic spirit for so long. That’s a part of it, not just the physical fact of flight and wanting to watch flight, but also the bird song and bird communication, this language that you can try as hard as you like to understand, and yet you can never be quite a native speaker. Those things have fascinated me. And I guess the questions that I still have about birds are mostly about what it’s like to be a bird. My main profession is as a falconer, working with birds of prey, bringing people out to watch the birds fly, and doing library programs like the one in Windham.

And that’s just been a fascinating new thing. Just living with birds and watching them day in and day out, you can start to answer some of those questions about what it must be like to be a bird. I think that’s a question that comes up in my poems and in poems of poets that I love.”

But falconry specifically, so maybe. It was an interest in birds, and then it became birds of prey, and then you want to learn how to work with these birds. There’s a progression.

“I have a hard time tracking it. It started very generally with birds wanting to know their names, wanting to know their songs, and wanting to get close to them. Oftentimes, birds are such a fleeting thing, you see them for a couple of seconds, and just at the moment you’re getting close, they fly off. So just that very basic desire to spend some time with them has made falconry appealing.”

“When you’re working with birds of prey at the beginning, for many weeks, sometimes months, they are not sure what to make of you. They fear you. They’re nervous about what might happen when they’re down with you. They don’t trust your glove as a safe perch at the start. But there comes a moment when you’re out flying with them, as you do each day, and you realize that they’re not even quite seeing you anymore. They’re just looking past you into the landscape. You are just part of their landscape, and they know you’re going to help them try to find something to catch. That moment of being adopted into their world is really special. You realize they’ve sort of taken you into their reality, even though you’re such a different creature from them. I mean, they’ve got moods and personalities, just as we do, and they spend the bulk of the day, probably digesting and preening and bathing and not doing anything particularly aggressive. So it’s a very interesting life.”

“I work with four birds currently, three hawks and one great horned owl. It’s been great. So many people generally, but kids, in particular, have deep connections to or interest in birds and the natural world when they’re young, you know, eight, nine, ten, and eleven. Then other concerns, sort of more human concerns, often take over, but to talk to kids at that age and give them a chance to be up close with a bird is really fulfilling and a little bit magical.”

Beverly Stoddart is an award-winning writer, author, and speaker. She is on the Board of Trustees of the New Hampshire Writers’ Project and serves on the board of the New Hampshire Center for Public Interest Journalism. She is the author of Stories from the Rolodex, mini-memoirs of journalists from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.