By DAMIEN FISHER, InDepthNH.org

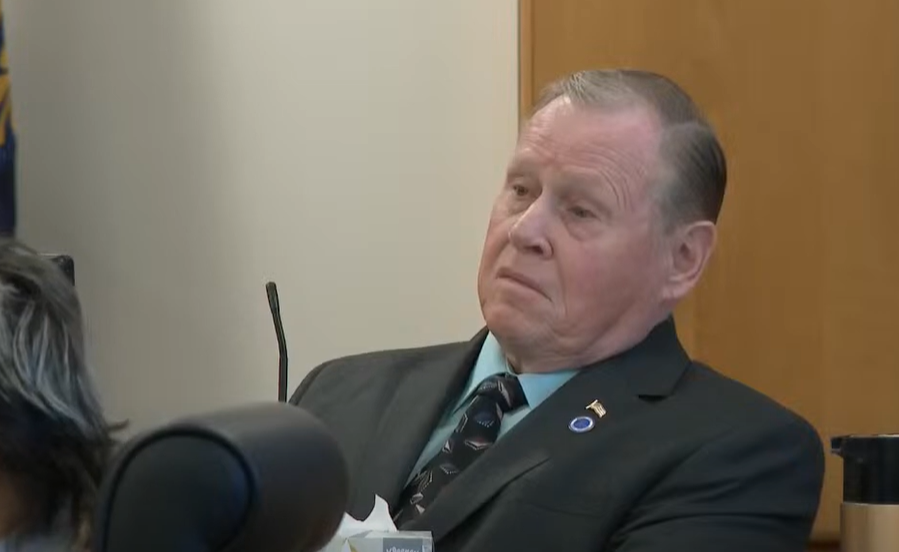

BRENTWOOD – Virgil Bossom watched in horror as serious allegations of abuse against staff at the Sununu Youth Services Center was ignored, the alleged abusers assigned to investigate their own abuse, and the children who brought the complaints disciplined for speaking out.

But, that was the way things were handled, Bossom testified Monday in Rockingham Superior Court, saying top YDC (then called Youth Development Center) administrators were not interested in hearing about problems, even if that meant ignoring allegations of physical assaults and rapes.

“(Superintendent Ron) Adams said, ‘I cannot take a kid’s word over a staff’s word,’” Bossom said. “That was very upsetting.”

Bossom, a former YDC staff trainer who was first called to the witness stand last week, testified again Monday in the first of more than 1,000 lawsuits filed against the state. The first plaintiff, David Meehan, alleges he was brutally raped, sometimes twice a day, and frequently beaten by YDC staff while the people in charge did nothing to stop the abuse. Meehan is seeking millions of dollars in damages for the abuse he suffered. If successful, the state is looking at a potentially crippling legal liability as the other survivors bring their cases to trial.

In his role as trainer, Bossom was also assigned in the late 1990s to investigate some of the complaints about staff assaulting children, but described a broken system that protected the alleged abusers, and silenced the children.

YDC policy on complaints about residential staff effectively allowed the staff committing the abuse to be the first investigators, Bossom said. For example, when Meehan and two other boys were caught trying to escape the facility, the two YDC staffers accused of raping Meehan on a daily basis were assigned to investigate the incident, according to testimony.

“It was not a good practice as I can see from here,” Bossom said.

Along with a lack of transparent and independent investigation, things like physical evidence of assaults were ignored, or downplayed by YDC medical staff, he said. Once staffers got themselves cleared, they made sure to discipline any child for speaking out by claiming the child filed a false report, Bossom said.

“The staff felt very powerful. The kids didn’t want to talk, knowing there would be repercussions,” Bossom said.

But the leadership did not want to know, he said. When he tried to get a sexual abuse training course established for residential staff, Bossom said administrators halted the plans, saying it wasn’t needed.

“I was told ‘we don’t need to teach people not to rape kids,’” Bossom testified.

The residential staff at YDC underwent little expert training before Bossom started working at the facility, he testified, calling their professional backgrounds for the work incomplete. When they did get trained on topics like appropriate use of restraints, or safety procedures, Bossom said residential staffers ignored best practices.

The residential staff knew enough to justify their actions, though, Bossom testified. The staffers frequently went alone into resident rooms, against policy. Every time they claimed they were responding to an emergency, he testified. “We gotta save the kids,” they told Bossom.

On many of Bossom’s investigations into the use of restraints or force by residential staff, Bossom said the staffers uniformly made nearly identical claims to justify their actions. The child they restrained almost always showed aggressiveness first by closing their fists, according to the reports Bossom reviewed as an investigator.

Asked by Meehan’s attorney David Vicinanzo if the internal investigations into staff abuse had any integrity, Bossom rankled a bit. He maintains his work as an investigator was done with integrity and the mission to seek the truth. Asked if his superiors conducted their part of the investigations with similar integrity, Bossom said they did not.

“No, not from leadership,” Bossom said. “Not at that point.”

Martha Gaythwaite, the attorney representing New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services, tried to knock Bossom’s credibility with the jury by painting him as a biased witness. While Bossom has cooperated with police detectives assigned to the Attorney General’s investigative task force, and with Meehan’s lawyers, he’s not been as helpful to the state’s defense team, according to Gaythwaite. According to the state’s lawyer, Bossom is blinded by his sympathy for Meehan after learning about the alleged abuse.

Gaythwaite asked Bossom about a phone call he had with a DHHS attorney during which she claims he hung up. Bossom testified he was driving in Maine when the DHHS attorney called, and the cell service dropped. He testified he was not obliged to call back, but Gaythwaite pushed, accusing Bossom of “picking a side.” Bossom denied he harbored an overt bias, but that he wanted to tell the truth.

“I picked a side I think of as justice, that’s what I feel,” Bossom said.

Once Bossom’s testimony finished late Monday afternoon, Meehan’s team called Rochelle Edmark to the stand. Edmark was hired at YDC in the late 1990s as one of the facility’s first ombudsmen, assigned to conduct internal investigations of complaints brought against staff. Edmark was met with hostility when she started at YDC, and blocked from doing her job. For example, she was denied basic access to the residential buildings by staff, she said. Edmark’s testimony will continue Tuesday. The trial is expected to go at least another week before it goes to the jury.

The livestream for Monday’s hearing, provided by WMUR, was marred by technical difficulties throughout the second half of the day. Rockingham Superior Court Judge Andrew Schulman recently denied a motion to have the trial streamed on the court’s Webex system.

Damien Fisher is a veteran New Hampshire reporter who lives in the Monadnock region with his wife, writer Simcha Fisher, their many children, as well as their dog, cat, parakeet, ducks, and seamonkeys.