By ANI FREEDMAN, InDepthNH.org

On Monday, the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute (NHFPI) hosted its first online webinar as part of a series addressing the state’s economy, Strengthening the Foundations of a Thriving Economy.

The first installment explained how child care in New Hampshire is currently suffering, leaving families without access to vital child care or unable to pay for it, while child care workers remain underpaid, burnt out, and their facilities understaffed.

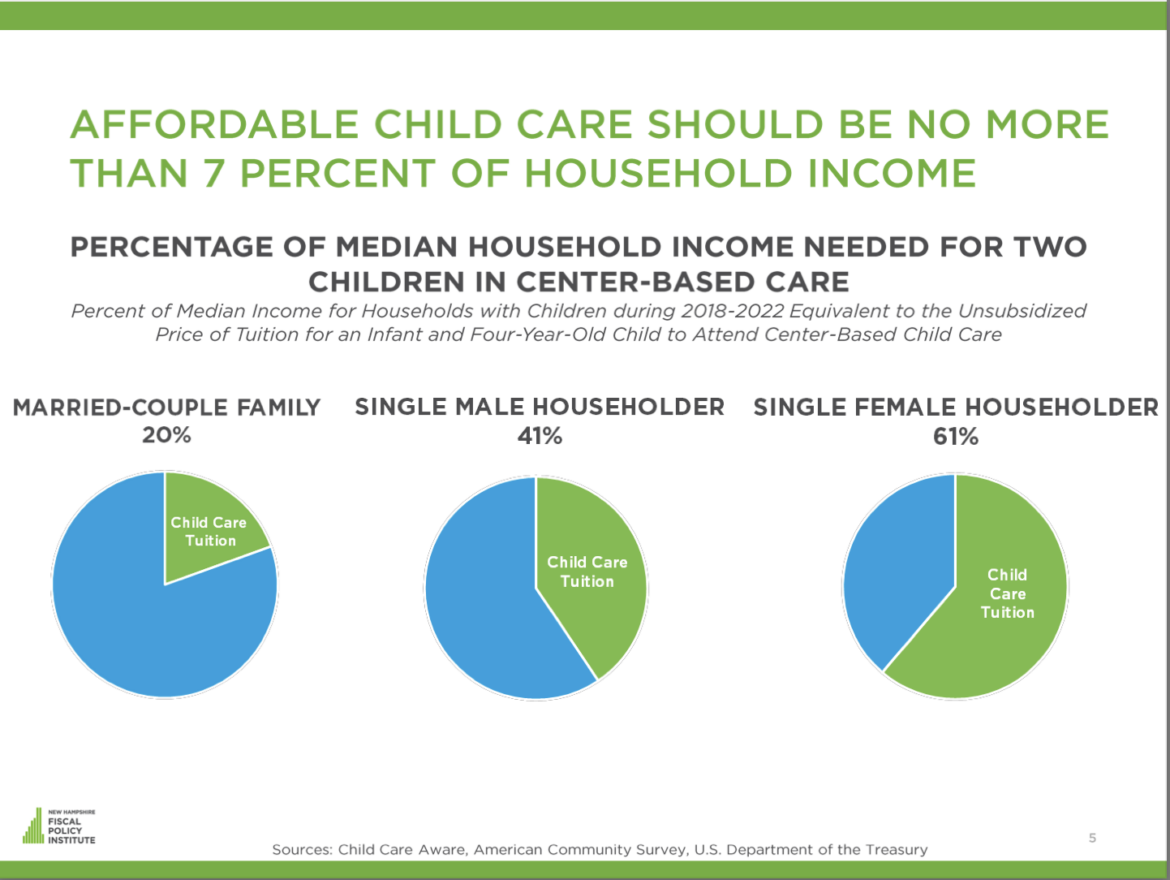

Nicole Heller, Senior Policy Analyst at NHFPI, provided an overview of the dire situation in child care for children under the age of five. For families, the cost is unaffordable, she said. Heller explained child care should be no more than 7% of household income, but for a female-led household, the average price of childcare for two children under five is equivalent to 61% of the median household income. Even for a married couple, Heller pointed out, the average price of child care in New Hampshire for two children under five is equivalent to 20% of household income.

Matthew Thorne, a father of three who spoke on the webinar panel, the cost of child care for his children is currently $600 per week—more than his family spends on housing or anything else.

“The stress of trying to do two basic things in your life, work and keep your job and raise your kids—it’s a lot,” Thorne said. “The daily stress of trying to make that equation work just kind of shows what a flop this system is.”

Thorne said his family has struggled to even access child care, living in a rural part of the state. And when they do find a child care center, the waitlists present another barrier. Thorne said his five-year-old child is still on a waitlist for one of the centers—over four years after they first applied.

“I think anyone with little kids right now that’s trying to work understands how wild the waitlist scene is when you’re just trying to get into a daycare,” Thorne said.

One of the core problems with child care in New Hampshire is burnout and lack of staff, said Shannon Tremblay, Director of the NH Child Care Advisory Council. Tremblay said not enough workers are coming into child care anymore, leaving facilities short-staffed and unable to reach full capacity of children.

“No one wants to come in for low wage, working long hours, in a stressful environment,” Tremblay said.

According to NHFPI, child care workers made roughly $32,500 in 2023. The United States Department of Health and Human Services’ poverty guideline for a family of four in 2023 was $30,000.

“We know that our child care workers are not making livable wages,” said Heller. She also said they often do not have access to benefits either.

Heller of NHFPI also pointed out the high turnover rate of 17% for child care workers in New Hampshire, above the overall job turnover rate of 11% for the state. As child care workers come and go, that disrupts the environments for children at young impressionable ages.

Thorne said he can see the impact it leaves on his children to have so many different teachers. He believes it’s vital for them to grow up with the stability of the same teachers, and it can become especially jarring for kids when their instructors change more frequently.

“It just disrupts these bonds,” Thorne said.

Tremblay emphasized that worker burnout puts some of the most strain on the New Hampshire child care system. Providers, she said, are dealing with stress from multiple fronts: staffing shortages, low wages, and little room to breathe.

“We’re one sick call away from having to close classrooms,” Tremblay said. Those child care workers rely on their jobs, however, to provide for their own families, but struggle to do so with such low wages. The median wage, according to NHFPI, is $15.62 an hour, or $32,490 per year. But that’s the median, meaning half of those child care workers are making below that wage as well.

“If providers can’t provide for their own families, how can they provide for other people’s families?” Tremblay said.

Within the facilities, workers are struggling too. She said oftentimes facility directors are having to play multiple roles, including teaching, cooking, and cleaning the facilities. Tremblay said she often sees directors in the classroom, in the kitchen, on the playground during Zoom calls. With facilities spread so thin, they can’t afford to give child care workers time off for vacation either, Tremblay said.

The bottom line is, they need more funding, Tremblay said.

While the one-time funds from the COVID pandemic provided a necessary boost to the child care system, it wasn’t enough—and NHFPI said those payments are stopping in September of this year. If anything, the COVID pandemic exacerbated issues in child care that were already there, said Sara Vecchiotti, Executive Director of the Couch Family Foundation, an organization based in New Hampshire that focuses on children’s health and development.

“The business model itself doesn’t work,” Tremblay said.

Tremblay said that the need for higher wages should not come at the burden of families, either. She said they need more support at the state and federal levels.

“We need the policy to change, we need wages to increase,” Tremblay said. “We just need to invest in our kiddos.”

Tremblay said those early childhood investments could present important long-term benefits as well. If kids with disabilities, behavioral issues, or mental health struggles need help, those issues could be identified early on to start building a support system earlier, Tremblay said.

If they were to have the proper funding and support, Tremblay was confident the state has plenty of facilities to meet statewide needs for care—they just need the workers to do it. “It’s not a matter of needing to build more child care centers to fit the need, it’s a matter of filling those child care centers,” Tremblay said.

As a parent, Thorne feels the lack of state support for children. He said he and his partner are a part of what’s called a “sandwich generation,” trying to juggle taking care of aging parents and young children, without much support to do either. He said they’re even thinking of leaving the state.

“If we did leave New Hampshire, it would probably be the first reason,” Thorne said. “To try and find somewhere with a little bit better support for our kids.”

Thorne said the instability of child care takes a toll on the kids, too, who absorb the stress of their parents and teachers at such a vulnerable stage in life.

“We need a different model or some help from the state or something,” Thorne said.

The New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute will be holding two more webinars about

Strengthening the Foundations of a Thriving Economy. The next will be held on Monday, April 29 from 11 a.m. to 12 p.m. and will focus on health. The third event of the series will focus on income and poverty, and will be held on Monday, May 13 from 11 a.m. to 12 p.m.

Ani Freedman is a contract reporter with InDepthNH.org. She is a recent graduate from Columbia Journalism School with a passion for environmental, health, and accountability reporting. In her free time, she’s an avid runner and run coach. She can be reached at anifreedmanpress@gmail.com.