By DAMIEN FISHER, InDepthNH.org

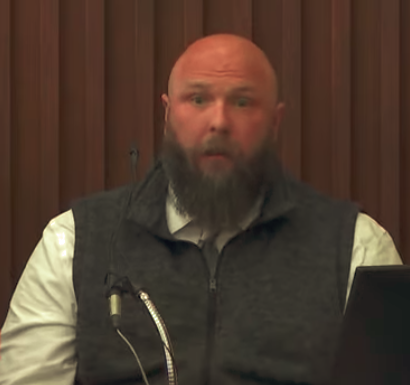

DOVER – Star witness Josh Colwell’s life as a dealer and enforcer in Dean Smoronk’s drug trafficking organization in the days leading up to the murders of Christine Sullivan and Jenna Pellegrini in Farmington was front and center Friday, even if he could not remember all the details.

Colwell is key to the state’s case against Timothy Verrill, another Smoronk associate who is charged in the brutal slayings. A strung-out and paranoid Verrill allegedly killed the women after he told Colwell that he suspected Pellegrini was working as a police informant.

“(Verrill) was acting weird and asking me if I knew who Jenna was. He asked if I thought she was an informant. I told him I did not know and told him to call Dean,” Colwell testified Friday in Strafford County Superior Court.

But Colwell’s account during Friday’s cross examination included memory lapses about his work for Smoronk and his whereabouts on the weekend of the Jan. 27, 2017, murders. Prosecutors showed jurors this week video from Sullivan’s home security system of Verrill at the house in the hours before the murder, illustrating the theory he was the only visitor to the home before the two women were killed.

However, when on cross examination Colwell initially said did not remember being shown how to operate the video camera by Smoronk days before the murders.

“I don’t recall that,” Colwell said.

However, the defense team showed jurors video of Colwell and Smoronk in the house on Jan. 25. The two appear to be looking and discussing the camera system in Sullivan’s house on Meaderboro Road in Farmington.

Verrill maintains his innocence and his defense team is trying to cast suspicion on Colwell and Smoronk as being the real murderers. Smoronk and Sullivan were a romantic couple and business partners in the drug trafficking ring. The relationship soured, personally and professionally, with Smoronk frequently telling people in his circle how much he hated Sullivan.

“Bro, I’m so f…ing sick of that bitch … I have got to get her out of my life ASAP,” Smoronk texted Colwell.

Smoronk was out of the state when the women were killed, flying to Florida on Jan. 26 and not returning until Jan. 29. Smoronk reportedly cut his trip short because he was worried after not being able to contact Sullivan, the woman he told his friends and associates he hated. He had Colwell pick him up from the airport on the return.

Colwell and Smoronk were getting close as business partners and friends in the weeks before the murders. Colwell invited Smoronk to spend time with him at the Mountain Men Motorcycle Club clubhouse, a space typically closed to outsiders. Colwell was also taking on more responsibility dealing with cocaine, setting up new customer tracking systems and a venture referred to as the “snowplow business.”

Colwell did not recall many of the details of how the “snowplow” operation worked when asked on the stand about many of the terms he used in texts with Smoronk and others. It was clear, though, from many of the texts, Colwell had customers lined up to buy cocaine from Smoronk.

“They are chomping at the bit to serve these accounts, heard we might be getting another snow storm,” Colwell texted to his friend and supplier.

Both Smoronk and Colwell turned witness in the investigation, and both men face legal consequences for their drug dealing. Smoronk was sentenced in 2019 to three and a half years in prison for dealing methamphetamine. Colwell was busted for dealing methamphetamine in 2018, but avoided prison when prosecutors recommended in 2021 that he be free on time already served pre-trial.

Colwell has an immunity agreement with prosecutors for his testimony in the murder trial.

This is Colwell’s second starring role on the witness stand against Verrill. He was featured in the botched 2019 trial that ended with prosecutors admitting three times they violated discovery rules by holding back exculpatory evidence. That resulted in a mistrial.