By GARRY RAYNO, InDepthNH.org

CONCORD — A state with workforce constraints and an aging population faces a stagnant economy without greater investment in higher education, a study finds.

It is well known that New Hampshire’s lowest in the nation investment in higher education results in some of the highest in-state tuition costs, and that is reinforced by the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute’s issue brief “Limited State Funding for Public Higher Education Adds to Workforce Constraints,” released Thursday.

The lack of investment means New Hampshire college students have the highest student debt in the country or nearly $40,000, and sends 56 percent of high school graduates to other states to attend four-year colleges, second in the nation to Vermont.

New Hampshire’s investment in both the community college system and the university system are below the national average, and its per capita investment in higher education is the lowest in the nation at $106.

The state’s per capita investment is less than one-third of the national average of $338 and $500 below Wyoming’s highest state’s investment.

To reach the national average, New Hampshire would need to provide $464 million in fiscal year 2023, or $318 million more than the current state aid to higher education.

The study finds New Hampshire spends $1.43 per $1,000 of personal income on higher education, while the national average is $5.22 per $1,000 of personal income.

With the state’s 2022 household median income at $89,992, the average household would allocate $128.69 toward higher education, although New Hampshire has one of the highest per capita incomes in the country.

While the state is on the low end of a number of methodologies, more and more jobs in growth areas require college degrees, the study notes, so “access to, and the affordability of, public higher education for Granite Staters is vital,” according to institute senior policy analyst Nicole Heller.

The study finds individuals with more advanced degrees require less state services, earn higher wages producing more local economic activity, and are better able to afford housing and contribute to the state’s revenue stream.

However, students with higher debt may experience less individual and family “wealth building” through home buying or investment savings, according to the study.

State funding for higher education has rebounded since the great recession when it was cut in half by lawmakers and is about on par with what the university system received prior to the cut, and is more than the community college system received before the reduction.

“For nearly a decade, CCSNH funding has tracked with and in some cases outpaced inflation, however, State support of the USNH has lagged behind inflation,” Heller writes. To keep pace with inflation since 2006, USNH would have needed to receive approximately $128 million in state appropriations in State Fiscal Year 2023, over $39 million more than what was appropriated.

Overall, state support for higher education in New Hampshire increased 13.7 percent between 2018 and 2023, while the national average was 27.5 percent.

Support for the community college system has tracked higher than the increase in the overall state budget from 2013 to 2023, according to the study, while the university system state aid has been less than the increase in the state budget during the same period.

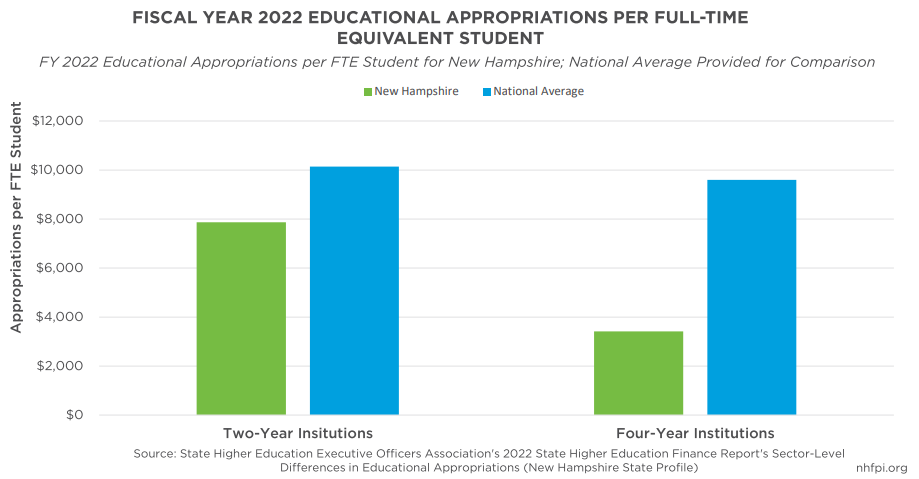

The study determines the amount of money the state provides for each full-time student in higher education.

New Hampshire invests the least of any state at $3,699.

The next lowest is Pennsylvania at $6,090, while the national average is $10,237 and the highest is Illinois at $22,970.

Vermont has more students than New Hampshire leaving the state to attend four-year colleges and that state provides $6,363 per student of state aid.

While Vermont sees about 58 percent of its students leave the state, Maine has the highest retention rate in New England with only 38 percent going out of state for a college degree.

Maine appropriated $7,838 per full time student at its four-year institutions compared to New Hampshire’s $2,494.

To match Maine’s funding level, New Hampshire would have needed to appropriate $201 million for fiscal year 2022, or $106 million more than it did.

If the additional money allowed New Hampshire to retain the same percentage of students as Maine, 1,329 more students would have remained in New Hampshire and would be more likely to remain here after college and join the state’s workforce, the study notes.

Over a 10-year period, that translates into 14,692 more workers, but the institute’ director of research Phil Sletten cautioned there are a lot of variables that could change that estimate.

The study also notes the high tuition costs at both the community college and university system institutions prevents high school graduates from attaining a higher education.

The number of graduating high school students who attend four-year and two-year colleges is expected to drop off considerably beginning in 2025, so competition for students in areas like New England with its high concentration of higher education institutions is expected to be intense.

Enrollments have dropped at all the schools in the university system and also overall in the community college system.

The study notes a greater state investment in higher education would result in a variety of long-term savings for the state as higher income levels reduce reliance on support programs such as food stamps, Medicaid and unemployment compensation.

The brief also suggests the state explore different funding methods employed by other states to provide a more stable financial environment for higher education.

“Educating Granite Staters and keeping young people in New Hampshire is vital for building a pipeline of potential workers to in-demand careers and for helping ensure a robust age-diverse workforce,” Heller writes. “By increasing State funding and considering use of thoughtfully crafted financial models developed in collaboration with public higher education institutions, New Hampshire could proactively create pathways to in-demand careers in the State’s labor force that require both two-year and four-year degrees using resources and systems that are already in place.”

The study is available at https://nhfpi.org/resource/limited-state-funding-for-public-higher-education-adds-to-workforce-constraints/.

Garry Rayno may be reached at garry.rayno@yahoo.com.