By NANCY WEST, InDepthNH.org

Two teenage boys have been returned to state treatment facilities after Child Advocate Cassandra Sanchez warned New Hampshire Bureau of Children’s Behavioral Health over a month ago they were being traumatized in a Tennessee facility contracted by the state.

The boys were flown back to the state with child protection workers Monday night, Sanchez said.

Sanchez first demanded their return and warned the state over a month ago of horrific conditions at the Bledsoe Youth Academy in Gallatin, Tennessee. They are receiving level 3 treatment under the care of New Hampshire. They are not in a facility because of criminal behavior.

“I was so happy for them to be in a safe place,” Sanchez said Wednesday.

Finally, she and her staffers can breathe and get a good night’s sleep knowing they are no longer at Bledsoe.

A week ago, Sanchez released a 17-page report Concerns for Out-of-State Residential Facility: Bledsoe Youth Academy documenting the concerns she found July 11 at Bledsoe.

See full report here: https://indepthnh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/OCA-Bledsoe-Issue-Briefing-3.pdf

“Our biggest concern is we see it as further traumatizing the kids,” Sanchez told InDepthNH.org last week.

Sanchez and Assistant Child Advocate Jennifer Jones toured Bledsoe finding it was run by staff through fear and humiliation behind a tall chain link fence topped with chicken wire.

At Bledsoe kids are offered incentives by staff to assault other “problematic” kids, the report said.

“…if a kid is giving staff a difficult time, another kid might be asked by staff to go after him physically and would be rewarded by staff with a snack or some other incentive, and the aggressor would not be written up for the behavior.

“Restraints by staff worry the kids and elicit fear due to observed injuries during restraints, specifically rug burns to their faces while in prone restraints on the carpeted floor. This was confirmed by the Program Director who stated, ‘yes that happens and so I have asked staff to use a towel or sheet on the floor first,’” the report said.

Some restraints involved arms being held behind them like ‘arm bars’ while pushed with their stomach up against a wall and lifted with feet off the floor by the restraining staff, according to the report. The boys told Sanchez and Jones they feared bedbugs and one said he was threatened with force-feeding if he didn’t eat the food even though he didn’t like it.

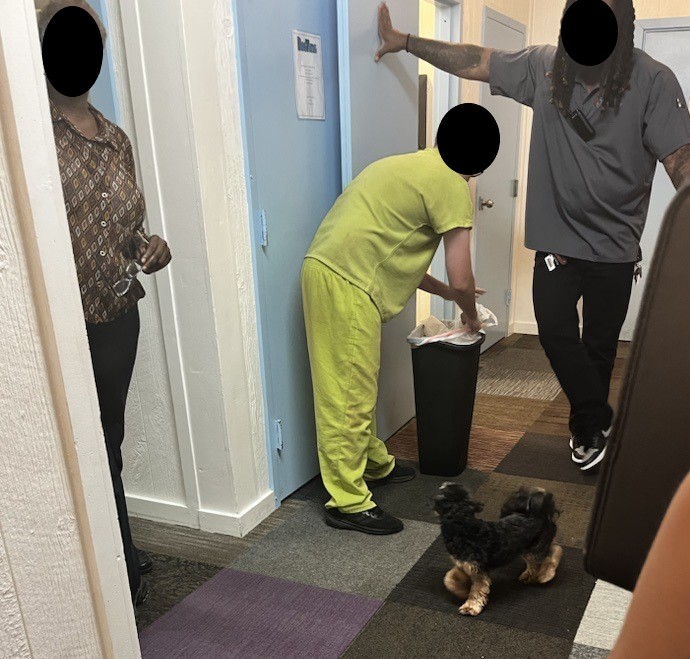

The report said the boys are required to wear different colored prison-like jumpsuits that broadcast the reasons they were placed there. Dangerous or violent boys wear a red jumpsuit; boys suffering disciplinary consequences wear a lime green jumpsuit; and those wearing tan jumpsuits are considered unsafe to themselves because of self-harm/suicidal ideation, according to the report.

Two Executive Councilors and a handful of lawmakers have reached out to Sanchez’ office since the report became public to see what can be done to avoid a similar situation in the future.

Sanchez said several ideas for proposed legislation have been discussed.

One idea Sanchez mentioned was to form a commission to study the residential treatment placement of children in and out of state and find out what’s working well.

It would include her office and a range of experts to look at long-term solutions.

She suggested that people who want to help situations similar to what children face in residential treatment facilities could become foster parents. There are currently too few foster parents available to meet the need, she said.

As July 1, there were 306 children in residential care, with 69 out of state.

Sanchez said the shortage of in-state beds could be caused by the certified facilities being maxed out or lack of staffing not allowing all of the beds to be filled.

The children in out of state placement are not there because of criminal behavior. If children are deemed delinquents, they would be sent to the Sununu Youth Services Center in Manchester.

The state pays up to $5,000 a month per child for an out-of-state placement to Bledsoe Youth Academy, whose parent company is Youth Opportunity Investments. They didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Sanchez said she hopes to meet with the two boys later in the week or early next week.

She previously expressed concern about what they have been through at Bledsoe.

“I do think it’s going to take lot of therapeutic support when these kids come back to New Hampshire. They are very resilient children with such strength to withstand this,” Sanchez said.

Residential treatment providers are ranked 1 to 5, with 5 being the most serious psychiatric residential treatment facility.

Levels 2, 3, and 4 are considered residential treatment facilities, which are differentiated by the amount of supervision, staff to child ratios and the intensity of the therapeutic treatment.

When Sanchez visited July 11, about half the building was under construction due to recent and extensive water damage caused by a sprinkler system activation in one of the kids’ rooms. Each bedroom sleeps five.

“Research tells us that children are significantly more likely to have grave outcomes such as homelessness, incarceration, and experience additional traumatizing events when placed in residential care,” the report said.

This concern becomes heightened when children are placed out-of-state, away from family and community connections, into programs that do not have the level of oversight as in-state programs, according to the report.