Above, the chain link fence around the Bledsoe Youth Academy in Gallatin, Tennessee, where two teenage boys from New Hampshire are supposed to receive treatment, but NH’s Child Advocate wants them immediately returned to a state facility instead. Photo from the 17-page report by OCA: “Concerns for Out-of-State Residential Facility: Bledsoe Youth Academy.”

By NANCY WEST, InDepthNH.org

Two teenage boys who are in the care of New Hampshire remain in a Tennessee facility despite Child Advocate Cassandra Sanchez warning the state a month ago that they are being traumatized there rather than receiving the treatment the state is paying for.

That could be up to $5,000 a month per child for an out-of-state placement to Bledsoe Youth Academy, whose parent company is Youth Opportunity Investments.

Sanchez and Assistant Child Advocate Jennifer Jones toured the Bledsoe Youth Academy in Gallatin, Tennessee, July 11 and interviewed the two boys who were placed there for treatment by New Hampshire.

The two boys were sent to Bledsoe for treatment not because of criminal charges and Bledsoe is not a detention center, Sanchez said in a telephone interview.

“Our biggest concern is we see it as further traumatizing the kids,” Sanchez said.

As to the state’s lack of action a month after being notified of serious issues with Bledsoe, Sanchez said, “My understanding is they are working on it. I do continue to ask this be a top priority that the boys come back.”

According to the 17-page report the Office of Child Advocate released on its findings regarding Bledsoe, Concerns for Out-of-State Residential Facility: Bledsoe Youth Academy, “there is a significant lack of ethical treatment and boundaries by direct care staff.”

See full report here: https://indepthnh.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/OCA-Bledsoe-Issue-Briefing-3.pdf

Sanchez and Jones spent two hours with the two New Hampshire teens.

“Disclosures were made that kids are offered incentives by staff to assault other ‘problematic’ kids.

“…if a kid is giving staff a difficult time, another kid might be asked by staff to go after him physically and would be rewarded by staff with a snack or some other incentive, and the aggressor would not be written up for the behavior.

“Restraints by staff worry the kids and elicit fear due to observed injuries during restraints, specifically rug burns to their faces while in prone restraints on the carpeted floor. This was confirmed by the Program Director who stated, ‘yes that happens and so I have asked staff to use a towel or sheet on the floor first,’” the report said.

It was described that some restraints involved arms being held behind them like ‘arm bars’ while pushed with their stomach up against a wall and lifted with feet off the floor by the restraining staff, according to the report.

Bledsoe is a level 3 treatment center, not for detention, despite the tall chain link fence that surrounds the perimeter of the building and what appears to be chicken wire across the top, Sanchez said.

Sanchez and Jones were so concerned by what they found that day that they immediately contacted the New Hampshire Bureau of Children’s Behavioral Health seeking to have the two New Hampshire boys immediately returned to a state facility. That was on July 11.

Sanchez said she is concerned about the overall culture of Bledsoe based on fear and humiliation.

“I’m very worried. I do think it’s going to take lot of therapeutic support when these kids come back to New Hampshire. They are very resilient children with such strength to withstand this,” Sanchez said.

“Overall, the OCA feels that this company has misrepresented what it can offer to the state of New Hampshire,” Sanchez said.

Her office has also filed an abuse and neglect complaint with the state of Tennessee and Sanchez worries the Bledsoe staff will retaliate against the New Hampshire boys because of her complaints.

Providers are ranked 1 to 5, with 5 being the most serious psychiatric residential treatment facility.

Levels 2, 3, and 4 are considered residential treatment facilities, which are differentiated by the amount of supervision, staff to child ratios and the intensity of the therapeutic treatment.

The 17-page report on Sanchez and Jones’ visit to Bledsoe recommended the immediate return of the two New Hampshire boys to a program in New Hampshire where they will receive adequate treatment.

It also recommends no further placement of children from New Hampshire at Bledsoe Youth Academy.

Messages left with Bledsoe and their parent company seeking comment were not returned Wednesday.

Jake Leon, spokesman for the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, said the department is grateful to the Office of the Child Advocate for their report and ongoing engagement with them on these cases.

“We take these concerns very seriously,” Leon said.

“Since the OCA first contacted the Department about its concerns, DHHS and DCYF leadership have proactively engaged with the New Hampshire youths at the facility, including arrangement of site visits as well as communication with Tennessee health and human services counterparts. The youths involved will receive individualized service plans to ensure their safety and determine the best course of action to get them on the track for success,” Leon said in an email.

There are currently 12 youths placed in residential care outside of New England, the lowest in memory, Leon said.

“In the new state budget, the New Hampshire Legislature provided new funding for contracted residential services in New Hampshire and neighboring states to increase high-quality bed capacity to ensure a system that helps kids receive top-notch care closer to home. In addition, over the past several years, the implementation of the juvenile justice and Children’s System of Care strategies has led to more youth receiving services in the community and fewer youth placed in residential settings. We will continue active collaboration with the OCA on all ongoing efforts to improve residential and community-based services and ensure the best possible outcomes for youth and their families,” Leon said.

Leon didn’t respond to questions about cost. Bledsoe charges up to $5,000 a month and treats up to 30 boys ages 12 to 18.

Leon was also asked if there are level 3 beds at facilities in New Hampshire that can’t be filled because of lack of staffing, but he didn’t respond.

Gov. Chris Sununu’s spokesman Ben Vihstadt referred questions about the OCA report to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Out of state placements are used as a last resort because they isolate children from their families and community supports and leaves them vulnerable without the proper oversight by state agencies, the report said.

“(Bledsoe) operates on a culture of fear and humiliation. To stay on the staff’s ‘good side’ one kid, who worked at a fast-food restaurant, brought back food for staff…”

He reported that if he brought back the specific meals requested, staff generally leave him alone.

“He stated that if he was unable to bring their exact ‘order,’ they might find ways to give him a hard time such as unjustified write ups (taking points from the point system, etc.),” the report said.

The teens reported staff as the most difficult part of the placement. One reported that staff read their files and use the information to berate and insult all kids into compliance.

“For example, they have heard staff say to other kids in the program ‘you are here because your uncle raped you’ and the kids reported being told ‘you are here because your mamas don’t love you,’” the report said.

When asked what it was like to be at Bledsoe, one teen became emotional.

“It’s horrible,” he told Sanchez and Jones.

The boys described not liking the food.

“One particularly noted that he refused to eat for a couple of days when he first arrived at the facility. He noted that he began eating after medical staff stated he was either going to ‘get a feeding tube down the throat or have an IV stuck in the arm’ if he continued refusal,” the report said.

The boys also reported concerns for bed bugs as they had been told by other children that they had bed bug bites.

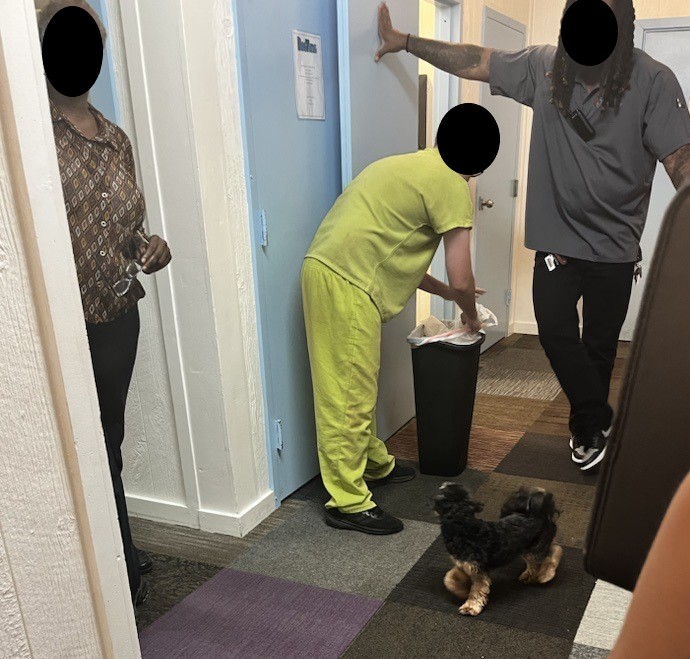

When asked about clothing and the significance of the specific-colored, prison style jumpsuits, Sanchez and Jones learned that they are used to indicate behavioral needs and/or punishment.

Dangerous or violent boys wear a red jumpsuit; boys suffering disciplinary consequences wear a lime green jumpsuit; and those wearing tan jumpsuits are considered unsafe to themselves because of self-harm/suicidal ideation, according to the report.

The New Hampshire teens said this was understood by everyone in the program.

“These ‘uniforms’ are not only dehumanizing and institutional, but they also violate each kid’s privacy by broadcasting to the community their personal struggles,” the report said.

“Bledsoe, although reporting to the state of NH to be a Level 3 residential treatment facility, is utilized as a juvenile detention center which was confirmed by the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services,” the report said.

The New Hampshire teens reported that many of their peers at Bledsoe have been adjudicated on serious and violent crimes.

About half the building was under construction due to recent and extensive water damage caused by a sprinkler system activation in one of the kids’ rooms when Sanchez and Jones visited. Each bedroom sleeps five.

Sanchez and Jones learned during the tour that one child had accidentally hit one of the sprinkler heads with his foot while laying on a top bunk, causing it to activate and was on “punishment for a month” for the damage caused.

New Hampshire currently has only 17 contracted level 3 programs from five placement providers (this includes assessment, intensive, and shelter placements – meaning some of these are extremely short stays), that even when fully staffed, cannot take all children in need of this level of care, according to the report.

“Research tells us that children are significantly more likely to have grave outcomes such as homelessness, incarceration, and experience additional traumatizing events when placed in residential care,” the report said.

This concern becomes heightened when children are placed out-of-state, away from family and community connections, into programs that do not have the level of oversight as in-state programs, according to the report.

The report said as of July 1, New Hampshire had 306 children in residential placements with 69 of them placed outside of New Hampshire.