Part One: New Hampshire newspaperman, Nick Pappas, explores the mine disasters.

ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO: For nearly 24 years, Nick Pappas worked at the Nashua Telegraph as editor including business editor, city editor, and editorial page editor. In that role in 2012, the paper ran an editorial causing the ire of the Nashua readers to call in and cancel their subscriptions. He wrote on November 11, “We didn’t run a corpse photo on the front page. Worse. We endorsed Mitt Romney for president.” Such were the issues for a newspaperman who was charged with writing opinions, especially opinions in a hot election time in New Hampshire. He explained those who disagreed with the call were Obama supporters and, “For them, it was a betrayal.”

Understanding Nick’s level of newspaper experience in the years he was in the Granite State he was named Editorial Writer of the Year by the New England Newspaper and Press Association in 2009 and again in 2011 and “was recognized by the New Hampshire Press Association with its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011.” In 2013 Nick moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, to be closer to family.

He resumed his newspaper career at the Albuquerque Journal, the largest circulation daily newspaper in New Mexico. Nick knew he had to continue to work and, as he says, stay out of his wife’s hair, which led him to explore two mine disasters that happened in Dawson, New Mexico in 1913 and again in 1923. He became aware of the tragedies when the Journal explored the 100th anniversary of the first mine explosion. In the 1913 explosion, 263 miners were killed. The 1923 event claimed 120 miners.

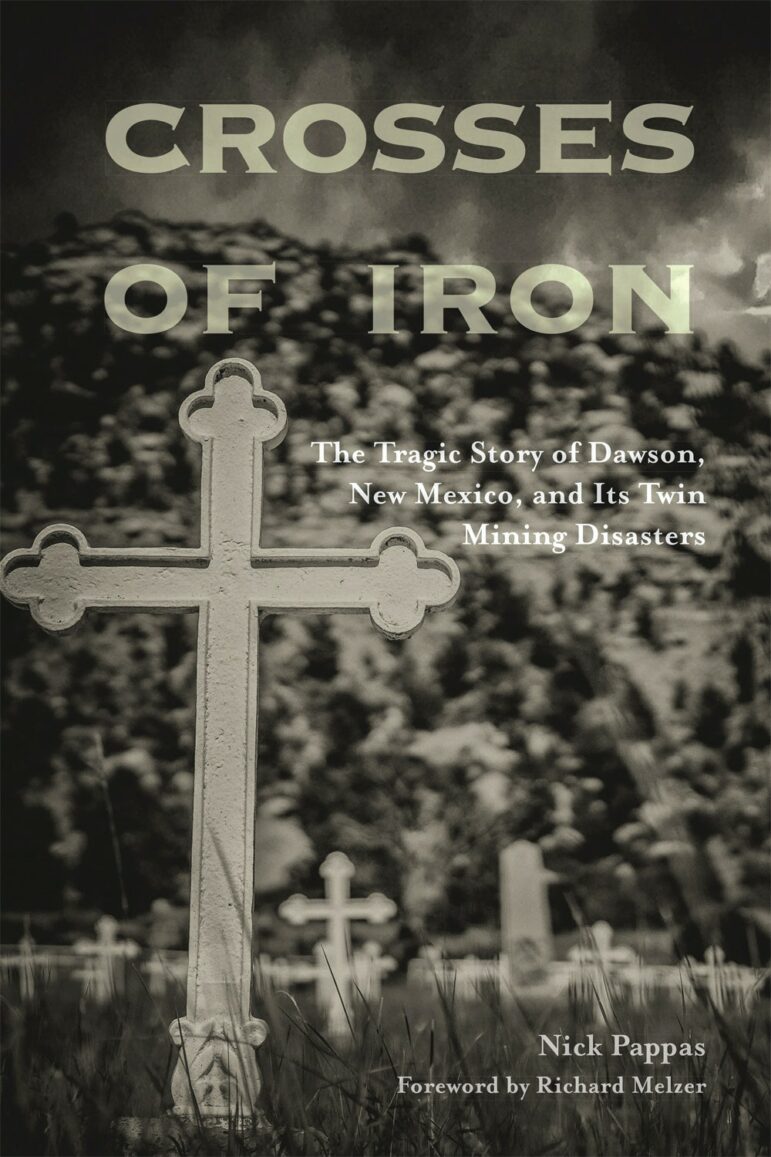

Nick’s new book, Crosses of Iron: The Tragic Story of Dawson, New Mexico, and Its Twin Mining Disasters, will be published this fall by the University of New Mexico Press. The book explores the tragedy by looking at the miners, who were mainly immigrants from Italy and Greece, among other nations, and diving into their lives and how so many came to New Mexico to mine coal and face coal dust and the accompanying respiratory issues, black lung disease, possible collapses and explosions in the mines that would snake their way into the earth for a mile or more. With the meticulous skill of a seasoned journalist, Pappas draws us into the lives of those who lived in the company town of Dawson, New Mexico.

We began our conversation with Nick talking about Dawson and the mining industry.

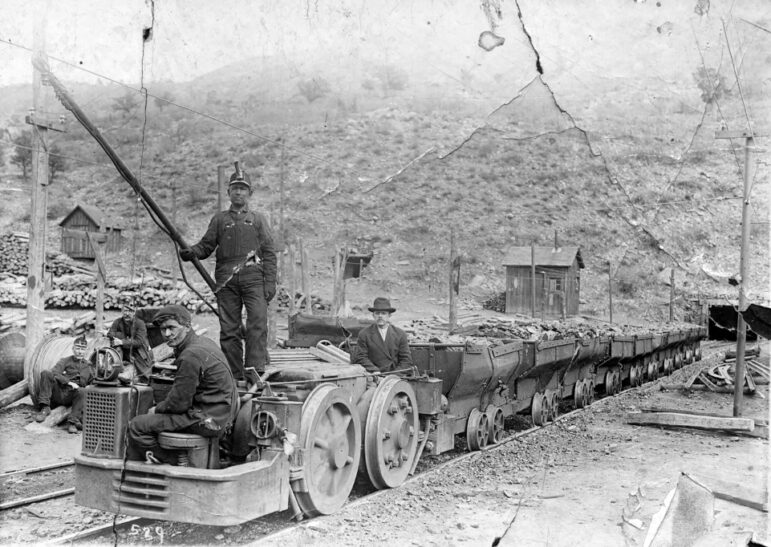

“Dawson, New Mexico, at its peak, had ten mines; both happened in Dawson, not the same mines. Originally in its heyday, the company-owned town had at least 6,000 people living there. It was modern in all respects, with businesses and recreation. They had an opera house and a huge 3-story mercantile store. That was in operation from 1901 to 1950. Phelps Dodge Corporation owned it for most of that time. They closed the town and the last mine in 1950. They hired an Arizona salvage company to bulldoze over whatever was left. I finally saw the town site for the first time last year. It’s a private ranch that you need permission to get on the property.”

“I tracked down the manager, told him I was working on the book, and asked if I could come in someday. I could finally do that in September a couple of years ago. There’s nothing left, a few foundations, maybe a house or two, and some rubble where some buildings were. The people I met up there let us in. It was myself, and at the time, the president of the Dawson, New Mexico Association, a gentleman who grew up in the town, and his wife. We packed up into a pickup truck and drove as far as we could on what used to be Main Street, a pretty bumpy passable road. We got in half a mile until it looked like we would get stuck and never be able to come out. It gave me a sense of the property. The great thing about having one of the Dawson natives there with me was as we were driving along, he was pointing out this is where my house was, where my dad parked his car, and where the hotel was. It helped get the sense of what it was like.”

Nick explained that the mines eventually were closed down by the Phelps Dodge Corp. due to changing economic conditions.

“In the early Twenties, they operated ten mines. One of their biggest customers was the railroads, Southern Pacific in particular. In time, the railroads switched from coal to diesel and lost one of their major customers. As time went on, in the Thirties and Forties, nationally, mining became a much more labor-intensive operation, with a lot of national strikes. The Dawson miners went on strike a number of times in conjunction with what was happening elsewhere in the country. It just got to a point where Phelps Dodge decided that this wasn’t worth it. You talk to people from there about why the town closed, and one will blame it on the strikes; one will blame it on changing market conditions. It was a combination of the two. Phelps Dodge had to go further and further in the mines to get coal which made it more challenging. In 1950, they closed the last mine. At that point, around 1,500 residents were given three months to pack up, get out, and move on elsewhere. A salvage company came in and sold everything. Some people moved houses. The location operates as a private ranch, and still to this day, the only thing open to the public is Dawson Cemetery which is on the historical register.”

The Dawson Cemetery was placed on the US National Register of Historic Places on April 9, 1992. The cemetery has three sections of burial grounds, and its Wikipedia site states, “is surrounded by barbed wire or iron pipe fences and it contains roughly 600 marked graves.” Nick visited the cemetery and described what he saw.

“I retired in December 2018 and in the middle of January 2019 drove out there to see the cemetery. There’s no one there, nothing. You drive down this road, and then it stops, and you get to the gate to where the ranch is and turn to the right, park your car, and walk up to the cemetery. What you see is this haunting sea of almost 400 identical white iron crosses, most with names, some without. Sections of the cemetery are dedicated to the miners who died in the 1913 mine disaster, and the people killed in the 1923 disaster are in another section. It’s just eerie. This is what you see, and other than the chirping of some birds in the background, there’s no sound. I spent 45 minutes walking around, trying to take it in and imagine what happened there. It was a moving experience. Then I started doing the research in 2019 and visited archives and libraries.”

Of particular interest to Nick was the notion that the Dawson community still exists today. The town is just a dusty memory, yet descendants keep the memory of their community and their families alive by gathering regularly.

“The mine closed in 1950. In 1954, the first Dawson reunion occurred in Pasadena, California, where many people had moved. Around the 1970s, they moved it to New Mexico, with the first taking place in Albuquerque. Then they got permission from the owners to open the town site every other Labor Day weekend, and they have a picnic reunion there. I went to my first one last Labor Day weekend, and there were almost 600 people there. During the peak years, going back to the 1990s, there’d be 1,500 people showing up to these reunions. This close-knit community still exists a quarter of a century since the town closed.”

But what can cause a mine to explode and kill 261 people? Nick’s narrative storytelling takes us into the mine and leads us to imagine what it’s like to be a mile deep in a mineshaft in 1913, where dangerous coal dust is floating and suspended in the air. Today’s CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states, “Coal dust has far more surface area per unit weight than lumps of coal and is more susceptible to spontaneous combustion.” Nick identified the miner who initiated the tragedy but asked that we not name him. However, he is identified in the upcoming book. He theorizes why the man would have been so bold as to use an explosion while the mine was full of people.

“In 1913, there were 280 people in the mine digging coal. At the time, they were using blasting powder to blast the coal off the walls in order to fill the carts and extract the coal from the mines. A miner decided to do that while everyone was still inside the mine, and he didn’t pack the hole properly. It set off an explosion, and instead of blowing in to blow the coal out, blew out. The mine was filled with coal dust which is explosive. It ignited the coal dust and sent an explosion all the way down the mine; 261 people died, and 23 people survived.”

“The official record, the coroner’s inquest, everything was identified as an unidentified miner. I was able to get a copy of the actual inquest, a Q&A of the people who were called in to be interviewed after the explosion. There was one name that came up a number of times. I can’t say with 100 percent certainty. I identify him in the book as the person believed to be responsible.”

“In those days, they had their cart to put their coal in, and it was brought in and weighed, and they were all paid based on the amount of coal they were able to extract on that given day. All the miners had identifying tags that had numbers on them that were used for two things. They would leave it at the mine house on the way in so that if the tags were still up on the wall, they knew the people were still in the mine. They also used that same tag to attach to the coal cart so that people could get credit for the coal they mined. His tag was right next to where the explosion occurred and where the cart was. It was a lot of evidence suggesting this was the gentleman who did it. Technically, it violated mine rules and state law at the time to set off explosives while people were inside the mine. The normal way of doing things is that people go in and do their work and leave at the end of the day. People would plant explosives in the mine and set them off electronically while no one was there. Miners would go in the next morning and start collecting some of the coal. In fairness, there were industry documents at the time that indicated this could be done but under certain conditions. But based on Phelps Dodge, mine rules and state law at the time, for obvious reasons, you weren’t supposed to do this.”

“The more coal you pulled out on a given day, the more money you made. That’s how they were paid. Had he packed this properly and blown out the coal in his area, he would have been able to pack more coal that day, have it weighed, and increased his wages on that given day. That seemed to be the motivation based on the investigation of the mine inspector.”

I asked Nick how do you recover 261 bodies. And in my curiosity, I did some searching on the web and discovered a seventeen-minute film of the recovery efforts at: https://archive.org/details/0633_Gould_can_5253_Dawson_Mine_Disaster_11_01_02_00

It is a free access download from the Prelinger Archives, which contains public domain material started by Rick Prelinger in 1983 and claims over 60,000 ephemeral films. Be warned, however, if you view the video, it has, as you can imagine, disturbing scenes. Nick talks about the recovery.

“It took a while, several weeks. They had this tagging system, making it easier to know who was in the mine and who wasn’t. After the explosion, people came from all over from other mines. There were two gentlemen who were on one of the rescue missions who ended up dying in the process. At the time, there was still gas in the mines. Using these rudimentary breathing apparatus that would last for a certain period of time. There are several reports on what happened. They overexerted themselves and went further than they should have. There was a rock fall. They tried climbing over going further into the mine, and either they ran out of oxygen, and one account has them taking their helmets off in panic. Gases in the mine were responsible for taking their lives.”

PART TWO: The death of a New Hampshire man and a Greek connection.

Beverly Stoddart is a writer, author, and speaker. After 42 years of working at newspapers, she retired to write books. She is on the Board of Trustees of the New Hampshire Writers’ Project and is a member of the Winning Speakers Toastmasters group in Windham. She is the author of Stories from the Rolodex, mini-memoirs of journalists from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.