By NANCY WEST, InDepthNH.org

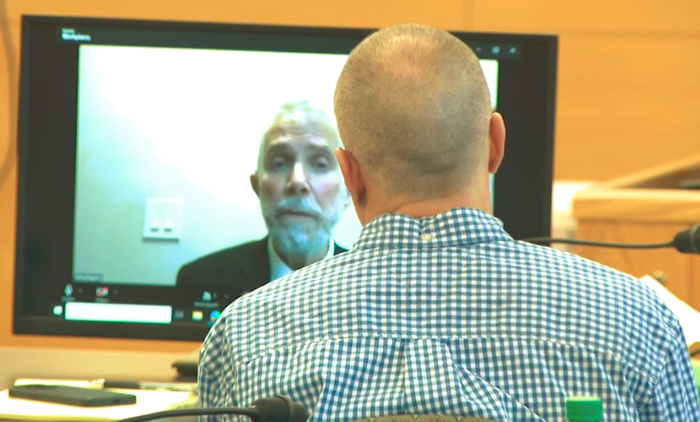

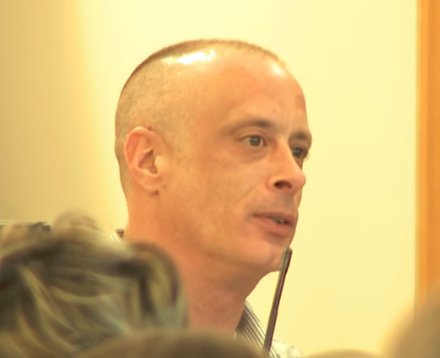

After 15 years of filing motions, lawsuits and conducting his own investigation, Scott Traudt’s 2008 assault conviction against the now Lebanon police chief has been vacated by a judge.

Grafton Superior Court Judge Peter Bornstein vacated Traudt’s conviction in a Jan. 3 order.

Bornstein said discipline against then-Lebanon Police Cpl. Richard Smolenski for having an extramarital affair with an 18-year-old woman while on duty and in uniform should have been disclosed to Traudt before his trial in 2008.

Traudt served one year in state prison for assaulting then-Sgt. Phil Roberts, who is now chief, during an altercation Jan. 14, 2007, after he and Smolenski stopped a car driven by Traudt’s then-wife for allegedly running a red light after the couple left a local nightclub.

Traudt, 57, of Strafford, Vt. has claimed ever since that he got out of the car to help his wife that night and was merely defending himself against two rogue cops who attacked him, then lied and claimed he assaulted them.

Traudt was also convicted of a violation level disorderly conduct offense. The jury found Traudt not guilty of assaulting Smolenski, who has since been fired from Lebanon police after being charged stalking a woman with whom he had a previous relationship. Smolenski is expected to go on trial in March on the misdemeanor charge and has pleaded not guilty.

“At the very least, the information should have been disclosed to (Traudt) because, given that his theory of the case was that the officers involved were renegade police officers and were not credible, the evidence of Smolenski’s investigation and discipline would have been relevant to that defense or otherwise used as impeachment evidence,” Bornstein wrote.

Lebanon Police Chief Roberts did not respond to a message Monday seeking comment.

Traudt, a former deep sea fisherman who now works delivering fuel, said Monday: “I’m gratified with the judge’s decision. I’m digesting everything going on right now and will comment later.”

Grafton County Attorney Martha Ann Hornick didn’t return a call seeking comment.

Traudt’s attorney Jared Bedrick said: “It’s been a long time coming for Scott. He’s a great example of someone whose perseverance paid off. He’s been fighting since day one.”

Bornstein detailed the motions and lawsuits Traudt filed in the past and noted that Traudt only learned of the existence of Smolenski’s discipline in a federal lawsuit in 2013 he filed against him and Roberts.

Traudt only received discipline details in a report in 2021 after the state Supreme Court somewhat relaxed rules regarding police discipline confidentiality.

The state argued that Traudt was too late in filing his latest appeal and his arguments had been made a number of times before, but Bornstein disagreed.

“The basis for the defendant’s delay is that the state only provided him with the Smolenski investigation report in 2021, despite the fact that the investigation occurred prior to (Traudt’s) trial in 2008.

“Although the disciplinary actions brought against Smolenski were expunged in 2008 shortly before the trial, the disciplinary actions were still in Smolenski’s file at the time the state brought charges against (Traudt) in 2008,” Bornstein wrote.

There is no doubt that the prosecution has a duty to disclose evidence that is favorable to the accused where “the evidence is material either to guilt or to punishment,” Bornstein wrote.

Generally, to get a new trial the defendant must prove that the prosecution withheld evidence that is favorable and material.

While it is up to the defendant to prove the evidence is favorable, it would then be up to the state to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the undisclosed evidence would not have affected the verdict.

Bornstein said the state didn’t meet that burden.

“First it is undisputed the state, either by the prosecutor or by the Lebanon Police Department, knowingly withheld evidence of Smolenski’s investigation from the defendant,” Bornstein wrote.

Nancy Gray prosecuted the case against Traudt, but could not be located for comment.

Smolenski had received a three-day suspension and six months probation for the affair and sexually inappropriate emails Smolenski sent to the young woman while on duty in 2006. He had also ordered someone with whom she had a conflict to stop harassing her, the order stated.

Bornstein noted that at trial the prosecutor claimed Smolenski was a credible witness because he had no disciplinary record.

There was “absolutely no evidence of any disciplinary mark on (Smolenski’s) record, no evidence of any prior complaint,” Bornstein quoted from then-prosecutor Nancy Gray’s closing arguments at trial.

“(Traudt) contends that if the state had disclosed it could have been used during cross-examination, as a basis for an objection to the state’s closing arguments, or even as a post-trial motion to set verdict aside,” Bornstein said.

Bornstein gave no credence to the state’s position that the evidence would not have been turned over to the defense because it says nothing about Smolenski’s credibility.

The state argued that Judge Steven Houran had reviewed Smolenski’s records in an unrelated case before Traudt’s case and found them to not be discoverable.

“As (Traudt) argues however, the evidence that complaints were made against Smolenski for engaging in an extramarital affair while on duty and using LPD resources to carry out that affair could have been used for impeachment purposes and was otherwise favorable to the defense.

“This is particularly true given the nature of the case and the state’s closing arguments,” Bornstein wrote.

The case against Traudt rested exclusively on the testimony and therefore the credibility and reliability of Smolenski and Roberts who were the only witnesses present during the physical altercation who could testify at trial about the charges, according to the ruling.

“The state is correct that the investigation into Smolenski does not make any finding that he lied to the police and that a judge had ruled the evidence inadmissible in another case, but the investigation does show there was information of a disciplinary mark on and prior complaints against him,” Bornstein wrote.

In state v Laurie in 1995, the state Supreme Court concluded that prosecutors’ failure to disclose the employment history of an officer violated the defendant’s right to a fair trial because the officer’s “testimony went directly to the issue of the defendant’s guilt” and a “major element of the defense strategy at trial was to discredit the behavior of the police,” Bornstein said.

The Laurie decision was the basis for prosecutors keeping Laurie Lists, now known as the Exculpatory Evidence Schedule, to identify police officers with credibility or excessive force issues to alert criminal defendants before trial.

“In this case, the jury acquitted (Traudt) of the assault charge against Smolenski and convicted him on the assault charge against Chief Roberts…” with Smolenski providing the primary corroborating evidence.

“In other words Smolenski’s testimony was a ‘major element’ of the case because he helped establish the defendant’s guilt as to the assault on Chief Roberts,” Bornstein wrote.

At trial Smolenski testified he saw Traudt “hit Sgt. Roberts hard enough to knock…him to the ground.”

“Given that the state’s closing argument at trial rested on the fact that Smolenski had no complaints against him and no evidence of disciplinary actions taken against him, the investigation into Smolenski’s conduct and the disciplinary action was relevant to the defendant’s case because the investigation records ‘reflected negatively on his character and creditability’ and an officer with a perfect record. Accordingly, the evidence of Smolenski’s investigation was favorable to the defense and should have been disclosed.”

The state argued that even if Smolenski’s discipline had been disclosed the outcome would have been the same.

Yet the only evidence at trial was the testimony of witnesses, meaning the jury had to base their verdicts solely on their credibility and reliability, Bornstein wrote.

Bornstein didn’t weigh in on whether it was improper for a prosecutor to tell jurors her personal opinion of witness credibility.

But given the importance of Smolenski’s testimony concerning the Roberts assault, Bornstein said he “cannot conclude the state has met its burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that the undisclosed evidence would not have affected the verdict.”