By MICHAEL DAVIDOW, InDepthNH.org

Summer is not quite over, but don’t tell that to my son. School is starting again this week. From now until next spring, he will need to get up, get dressed, eat breakfast, then stand on a local street corner in a foul mood so some bus can whisk him away to an institutional learning facility. My job in all of this is to cram a pop-tart into him and make some cutting remark when he fails to wear matching socks.

Just kidding. It’s to model good behavior here at home, so he can regale us at dinnertime with stories of how debauched the other kids are. “They get to watch tee vee in their underwear,” he will say. And I will tell him that I don’t care. (His mother will probably remain neutral in this debate because she will be “exhausted,” which is a word that can only legally apply to mothers. If you are not a mother, you can be “tired,” “fed up,” or even “dead,” but you can never, ever be “exhausted.”)

A friend once told me that having kids changes just one thing in your life, which is “everything.” I laughed when she said that because I liked my life as it was and I figured she was exaggerating, the way you do when you’re trying to make a point to someone who isn’t getting it. Turns out she wasn’t making a point at all; she was just describing the fact situation.

One part of everything, anyway, is politics, and my politics has changed quite a bit since this child entered our lives, for the simple reason that having a child makes you rely on your community much more than being alone. Schooling, health, religion, sports, the sponsoring of healthy relationships with others: not only can’t you do any of those things particularly well on your own, you find that many of those things don’t even exist outside the boundaries of community.

This is counter-intuitive in many ways, because we spend so much time and energy as we get older in honing our individual skill sets and trying to grow as individuals. We value the arts, especially, which largely exist as a means of self-expression. We like mavericks, we pride ourselves on “being ourselves,” and we tend to look with pity on those who are bound by convention and forced to act in ways that others demand.

That is our great liberal heritage, in the original meaning of the term: the classic belief that an individual has real worth when he or she stands on his own, and that the true goal of society should be that each individual develops to his or her fullest potential. When that idea was new, it clashed with the needs of the existing power structure: the church, the army, the landed aristocracy. Hence the supporters of that power structure took the name of conservatives; they were trying to conserve the older ways of doing things. And out of that clash came the great English civil wars; out of that clash came the French and American Revolutions; out of that clash came us.

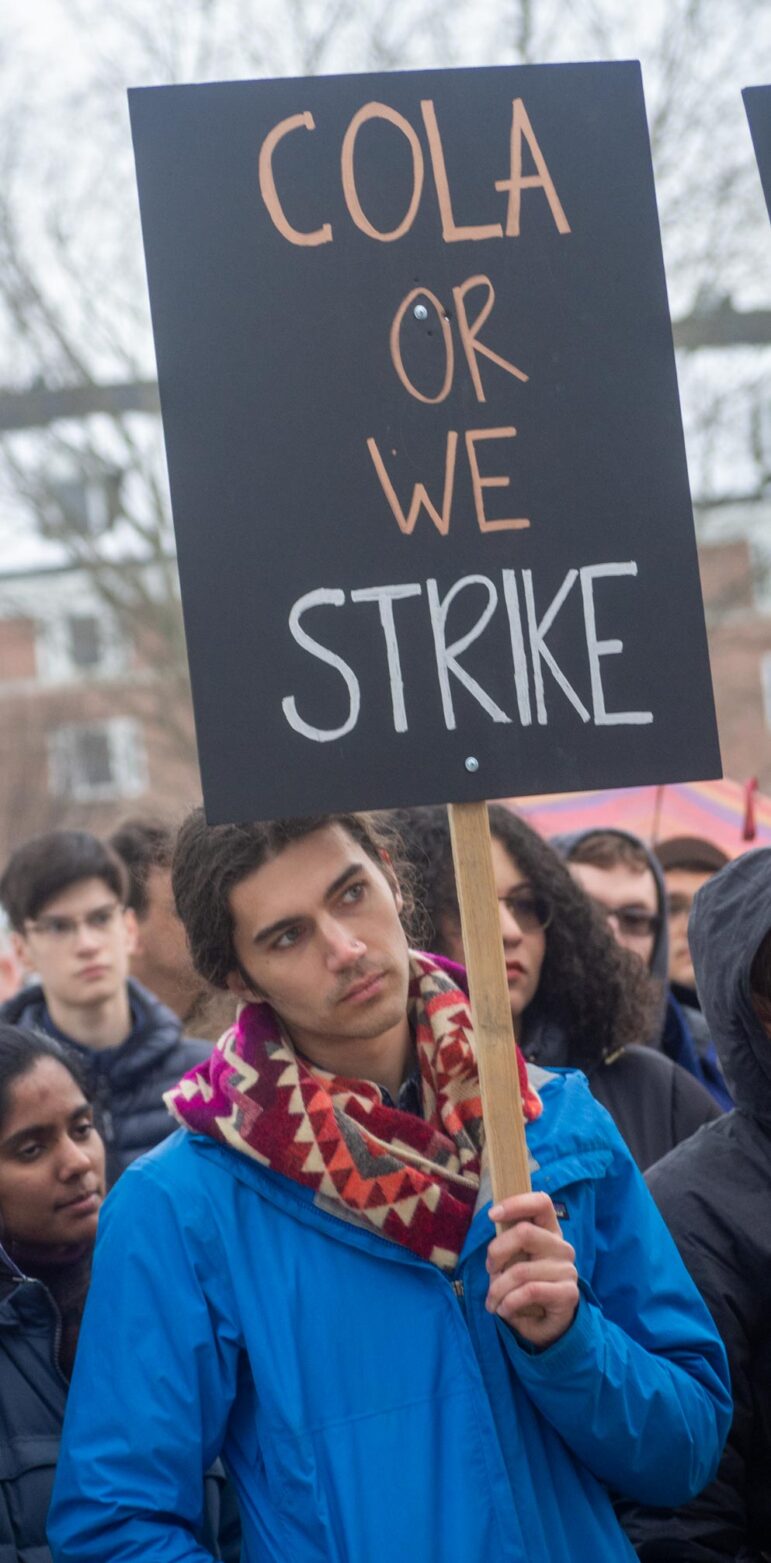

Growing to adulthood in this country is largely a liberal premise and it is often the young among us who are the most genuinely liberal for that reason. Having a child, then, brings balance to the equation. By throwing you back on your community for support, it reminds you of how important our oldest institutions remain, while it simultaneously teaches you how fragile they are; how they themselves only function properly when all parties involved take them seriously.

A healthy society needs both liberals and conservatives; the first to keep people honest, to make sure that happiness is never forgotten, to make sure that life itself remains valued; the second to give structure and support to that possibility of happiness, to make sure that the practical does not get destroyed for the sake of the ideal, to warm us when we are cold and we are too stubborn to leave the storm.

In every family, we embody this conflict with the natural roles of child and parent. I like playing the conservative in our home. I like telling my son that his socks should match, and I like hearing him tell me that it isn’t important.

The funny thing is that he’s right. In some ways, at least. But in other ways he’s wrong. He may just have to wait until he is a father himself to find out how.

He is the author of Gate City, Split Thirty, and The Rocketdyne Commission, three novels about politics and advertising which, taken together, form The Henry Bell Project, The Book of Order, and his most recent one, The Hunter of Talyashevka . They are available on Amazon and Barnes and Noble.