By Arnie Alpert

Active with the Activists

March 8, 2022

My first memory of Renny Cushing is probably a photograph. In it, Renny is carrying a suitcase with “Seabrook or Bust” painted in big letters. Since Renny was on his way to a Clamshell Alliance demonstration at the Seabrook nuclear power plant construction site, where he expected to get arrested, the double meaning struck me as clever. It was classic Renny.

Only later did something else occur to me. Most of the Seabrook protesters, myself included, were college kids or recent graduates, hailing from places like Amherst, Cambridge, and Durham. We marched onto the site carrying our changes of clothes and jars of peanut butter in backpacks.

But Renny wasn’t a college kid, he was a local kid, from Hampton, where he grew up just a few miles from the site where Public Service Company of New Hampshire (PSCo, as it was then called) wanted to build the “nuke.” Renny brought his change of clothes in a suitcase, the gear that at the time was still more typical for working- and middle-class people going on a trip. For Renny, the campaign to stop the nuke was first and foremost the defense of his own community from a threat imposed by big corporations with the backing of the state and federal governments. For Renny the adage that “all politics is local” was a way of life.

My first close collaboration with him came a bit later. Renny’s father, Robert R. Cushing, Sr., had purchased shares of PSCo stock for each of his children. The shares gave them admission to the company’s annual meetings of stockholders. Since my grandmother also owned stock in the company, I was able to attend as well with her proxy.

Even without dissension, a corporate annual meeting is an act of theatre, carefully staged by the management to impress investors. When stockholders publicly object to the management, the show takes on a different character. If I correctly recall with 45 years or so of hindsight, Renny nominated his brother Kevin to serve on the company’s board of directors. His nominating speech explained the hazards of nuclear power, both for the community’s and the company’s health. It was classic Renny, an unexpected message in the right place at the right time to the right audience.

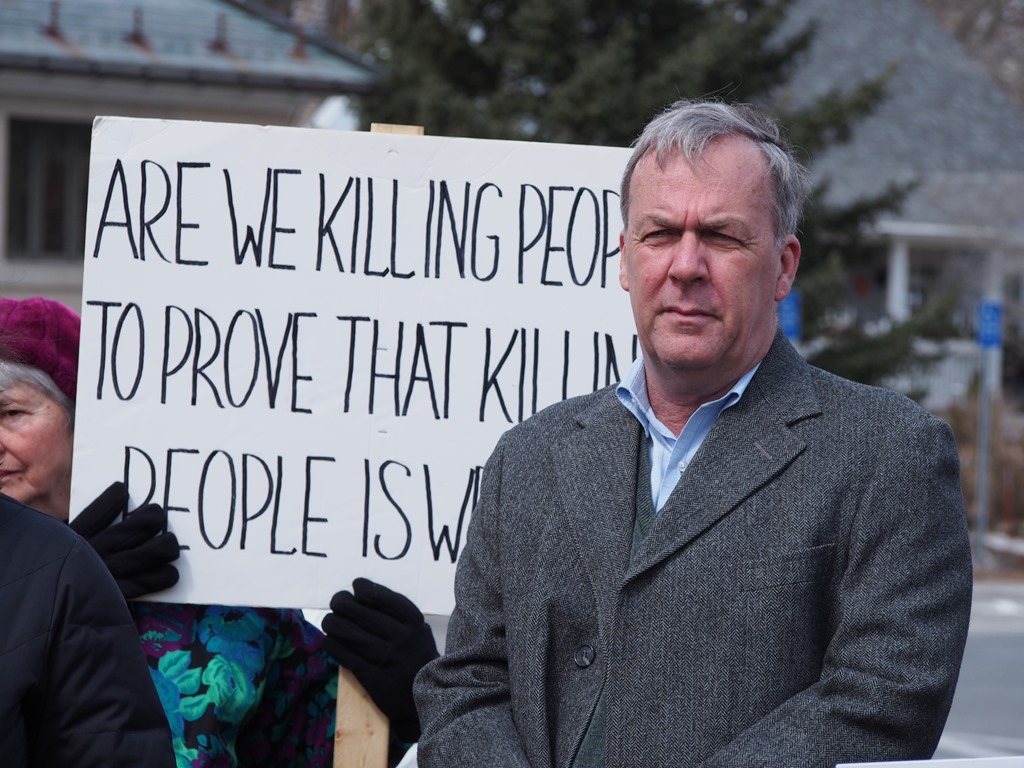

Renny did it again in 1998, by which time he was a member of the NH House of Representatives. Following a spate of gruesome murders the previous fall, the House was debating legislation to expand use of the death penalty. Renny took the speakers platform and told a sobering story about his father’s murder ten years earlier.

Robert Cushing, Sr. was watching the Celtics on TV when he answered a knock at the front door. “Two shotgun blasts were fired through the screen, lifting him up and hurling him backwards, the shrapnel lifting the life out of him before my mother’s eyes,” Renny told the assembled lawmakers. “The most difficult thing I have ever had to ask anyone was for help in getting my father’s blood cleaned off the floor and walls,” he explained.

With his infant daughter, Grace, in her mother’s lap in the House Gallery, Renny told a rapt audience of lawmakers, “If we let those who murder turn us to murder, it gives over more power to those who do evil. We become what we say we abhor. I do not want the state of New Hampshire to do to the man who murdered my father what that man did to my family.”

What survivors want, he went on, is to know the truth about what happened, to have some form of justice, and to have the opportunity to heal. Killing the killer does none of those things, Renny explained.

It was an unexpected message in the right place at the right time to the right audience and it turned the debate over the death penalty upside down. The expansion bill went down to defeat, and a campaign to repeal the state’s death penalty was soon launched.

The death penalty repeal campaign was a team effort, but Renny’s moral and political leadership was essential. As we went from year to year, governor to governor, defeat to defeat, Renny always made sure we left the door open for opponents to become allies. It took us twenty years.

It may not have been his intent, and surely was not when he first ran for office, but over those years Renny became a master of legislative procedure and honed his principled ability to forge alliances in unexpected places. As he transitioned from young upstart to respected veteran, Renny plunged into a wide range of policy debates, including victims’ rights, creation of a forensic psychiatric hospital, and medical cannabis. When the death penalty was finally repealed, I thought Renny would give himself permission to retire. But he still had items on his legislative to-do list, including marijuana legalization and acknowledgment of New Hampshire’s indigenous heritage.

It was after he was diagnosed with terminal cancer that Renny put himself forward to be his party’s leader in the NH House. That he used “RepRennyCushing” as his email address is an indication of how much his identity as a lawmaker meant to him.

But I remember, too, when email became common enough that lots of people were getting accounts and choosing their first email identities. Renny’s was “PapaCush,” a nod to his three daughters. Whether he was traveling the world for human rights, waging procedural struggles in the halls of the State House, or joining progressive candidates for president on the campaign trail, Renny cherished his family above all. He died on March 7 in the home where he grew up. He never stopped being a kid from Hampton.

As Renny entered his final days, lyrics of a Pete Seeger song came to mind.

“I’ll keep pluggin’ on,

Your face will shine through all of our tears.

And when we sing another victory song,

Precious friend you will be there.”