By Arnie Alpert

Much has already been written about the “teacher loyalty” bill expanding on one based on the extreme anti-communism of the Cold War era. HB 1255, still in the hands of the House Education Committee 4 weeks after it was discussed at a public hearing, would prohibit teachers from advocating “subversive doctrines” by expanding a 1949 description of banned doctrines. In addition, it specifies, “No teacher shall advocate any doctrine or theory promoting a negative account or representation of the founding and history of the United States of America.” That would include, but not be limited to, “teaching that the United States was founded on racism.”

To understand the roots of HB 1255, it’s helpful to go back to a time decades before McCarthyism.

During World War I, crackdowns on dissent focused on German sympathizers and anti-war activists. But after the war and the Russian Revolution, suspicion shifted smoothly to anarchists and communists, especially immigrants from eastern Europe. Although federal wartime laws enabling the jailing of activists such as Eugene V. Debs were no longer valid, dozens of states stepped into the void. According to historian Robert Murray, “by the year 1921, there were thirty-five states plus two territories (Alaska and Hawaii) which had in force either peacetime sedition legislation or criminal syndicalist laws, or both.”

New Hampshire was no exception. According to historian David Williams, A. V. Levensaler, who headed the new Concord office of the Bureau of Investigation (later to be renamed the FBI), drafted the state’s sedition law, which was adopted by the legislature and signed by Governor John Bartlett in March 1919. The law made it a crime to “advocate or encourage by any act or in any manner” the overthrow or change of government of the United States, the State of New Hampshire, or any of the state’s subdivisions. In addition to criminalizing such advocacy in public or private settings, the law banned the publication, distribution, and possession of any printed or written material, including pictures, deemed to be of seditious intent. Any such materials were to be seized and destroyed.

Another section of the law made it a crime to advocate, incite, or encourage “the violation of any of the laws of the United States, or this state, or any of the bylaws or ordinances of any town or city therein.”

The penalty for violation was up to 10 years in jail, a fine of up to $5000, or both.

Williams describes one incident in which a Lincoln resident complained to a state senator that the law infringed on free speech. His name was turned over to the Bureau of Investigation, where it was added to a growing list of radicals.

Although it was a state law, not a federal one, Levensaler and his Bureau colleagues proceeded to stage warrantless break-ins, plant listening devices, cultivate informers, and hire infiltrators to identify radicals inside New Hampshire’s unions and ethnic social clubs. By the end of 1919, they had a list of “subversives,” all immigrants who could be deported for espousing radical ideas.

It didn’t take much to get on that list, either. Being a union member, or simply hanging out at Manchester’s Tolstoi Club or Joe’s Russian Baths in Claremont, was enough.

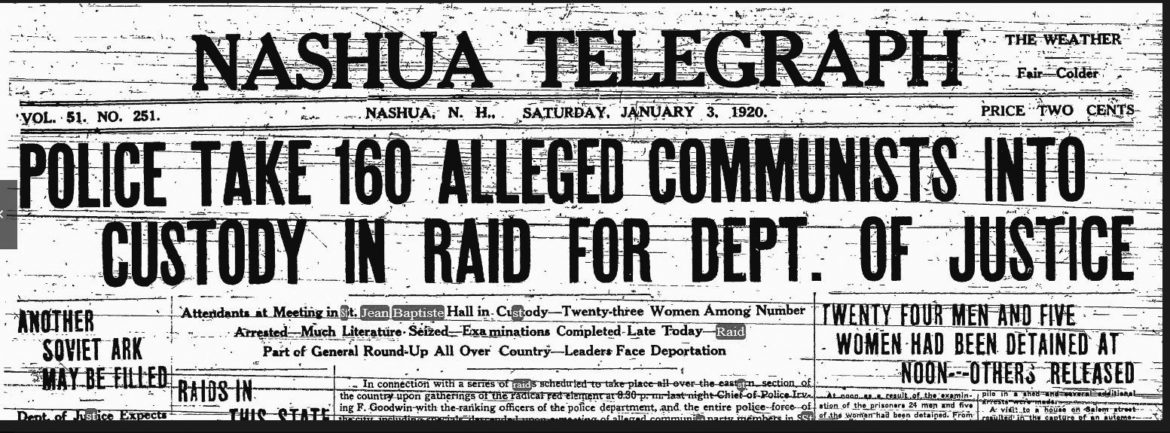

By the end of 1919, federal agents all over the country were ready for what became known as the “Palmer Raids,” named for the Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. On Friday evening, January 2, 1920, federal agents and local police swept through eight New Hampshire cities and towns, searching for people they asserted were dangerous radicals. When the raids were done, nearly 300 New Hampshire residents were in custody, seized from private homes, businesses, and meeting halls in Nashua, Manchester, Derry, Portsmouth, Claremont, Newmarket, Berlin, and Lincoln.

Nationwide, the raids netted as many as 10,000 people in 33 cities. The seizure of 141 people at the St. Jean Baptiste Hall in Nashua was the largest single mass arrest in the country. The raids also advanced the career of a young Department of Justice attorney, J. Edgar Hoover, whom Palmer had appointed to head the General Intelligence Division (originally named the “Radical Division”) inside the Bureau of Investigation.

It’s not clear to historians exactly how many suspected radicals were actually deported. It is probable that most of them were released due to the flimsy evidence against them and the illegal nature of the arrests. But even those who were released were subjected to appalling conditions of confinement, in some cases lasting months.

The Palmer Raids marked the climax of the first Red Scare, but it wasn’t the end. For example, Congress made it a deportable offense for “aliens” to even possess radical literature. Hoover continued spying on and attempting to destabilize radical groups all the way through the 1960s. In the words of historian Regin Schmidt, “institutional and bureaucratic anti-radicalism, once introduced and established in 1919, became a permanent feature.”

In the second Red Scare commonly associated with Senator McCarthy, New Hampshire adopted a law banning “subversive activities” in 1951 and two years later appropriated funds to enable Attorney General Louis Wyman to investigate cases of subversion. Wyman looked high and low, including among the UNH and Dartmouth faculty. He interviewed 130 witnesses under oath and more on an informal basis. He sent two men (Willard Uphaus and Hugo DeGregory) to jail for refusal to cooperate. Yet, after an investigation he claimed took “two and one-half man years,” he never charged anyone with the crime of being a “subversive.”

Perhaps that was never the point. The first Red Scare, according to Schmidt, “was, at bottom, an attack on … movements for social and political change and reform, particularly organized labor, blacks and radicals, by forces of the status quo.” The same could be said about the second one, which cost many people their jobs and caused even more to live in fear that someone would put their names on a list for writing, saying, or believing something that was deemed dangerous by those in power.

Let’s not launch a new Red Scare. Instead of policing the teaching of American history, the legislature should learn from it and send HB 1255 down to defeat.

The opinions expressed in op-eds are those of the writer. InDepthNH.org values differing opinions. email nancywestnews@gmail.com