By Thomas P. Caldwell, InDepthNH.org

CONCORD — Describing the proposed Dalton landfill as the largest project that the state Department of Environmental Services has dealt with in the past 50 years, members of the bureaus reviewing the permit applications attempted through an online information session to shed light on the review process in the light of public complaints.

Their effort was not totally successful. Dalton resident Eliot Wessler said, “My takeaway is DES provided a lot of hand-waving but very little in the way of providing specific answers to the specific questions.”

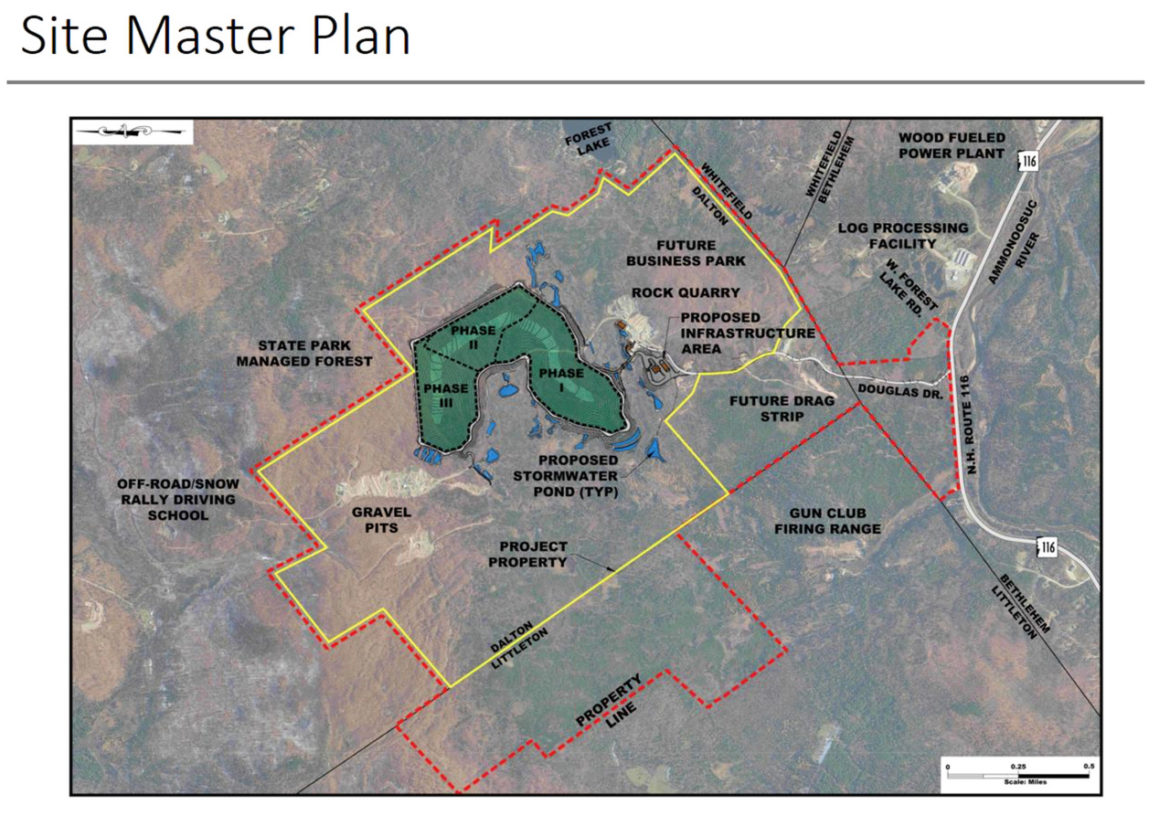

One of Wessler’s questions concerned the analysis of alternative sites. North Country residents have emphasized the proximity of Forest Lake State Park and their concerns about potential pollution of the nearby Ammonoosuc River. They maintain that it is the worst possible place for a solid waste landfill operation.

“Why not require a robust alternative analysis?” Wessler asked.

Phil Trowbridge, administrator of the Land Resources Management Program, said the agency has adopted a new rule concerning alternative site analysis, but that they had smaller projects in mind when they established the rule. “We’re thinking about how we’ll evaluate this in light of the new rule,” he said.

Currently, a developer sets the guidelines for determining how appropriate a site is. “The criteria drive the process,” Trowbridge said, admitting that “The approach that was used made some assumptions.”

Those assumptions included avoiding the proximity to airports and population centers. Granite State Landfill, a subsidiary of Vermont-based Casella Waste Systems, eliminated Massachusetts from its list of potential sites, saying that none of the 13 sites examined in the Bay State met all of that state’s criteria. Massachusetts has not approved a new landfill since the early 1990s.

Opponents of the Dalton landfill claim that nearly half of the solid waste that would go there will come from out of state. Mike Wimsatt, the director of the Waste Management Division, said the state only considers New Hampshire’s solid waste needs in determining the necessary capacity as part of its public interest analysis.

The largest complaint that speakers voiced was the Wetlands Board’s decision to ask for an amended application that would focus only on the first phase of the planned three-phase project. Trowbridge explained that the board can issue only a five-year permit with the option of a five-year extension, and that Phase 1 would take 15 years to build out. It would be pointless to consider anything beyond 10 years.

Todd Moore of the Air Resources Division explained that part of the reason for considering only the short-term impact is that rules tend to become more stringent as time passes, and if they were to approve all three phases, the project would be subject only to the old conditions. The next phases would be considered under potentially stricter requirements.

Trowbridge also said the extension is intended to synchronize the review between the agencies. The project requires 12 state permits as well as a federal permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Wimsatt said the solid waste application is limited to meeting the current capacity needs, which could change by the time the next phase begins.

More than 30 people signed up to speak during Wednesday night’s virtual information session, and the department extended the session to five hours to accommodate all those wishing to ask questions. Moderator Ken Finemore, who works in the Dam Bureau, noted that the information session was not required by rule or law, but was scheduled in response to the public’s interest in the review process. Many people are not aware of the regulations under which the agencies must operate.

There was a great deal of complaint about the way the DES works behind the scenes with applicants to obtain the information needed to make a decision, while limiting exchanges with residents to public hearings. Wimsatt explained that they are required to help applicants navigate a complex set of requirements, but that they listen to all the comments they receive from the public.

“We often meet with applicants so they understand what we need,” he said. “If we don’t have the information, it’s not fair to anyone.”

He continued that it would be inappropriate to strategize with those who want to stop a project from going forward. “We don’t have a responsibility to stack the deck,” he said.

Many speakers challenged the panel on their impartiality, asking why they didn’t reject the applications when the company failed to provide requested information. Part of the reason for asking for an amended application from Granite State Landfill was because the expected hydrology report had not been filed.

Trowbridge responded, “We encourage them to submit an alteration of permit application at the same time,” but they cannot force the company to do so.

Adam Finkel emphasized the importance of allowing the Dalton Conservation Commission to visit the site so they can provide comments on the plan. GSL allowed them on-site only once, when there was snow on the ground.

“I assume you’ll instruct the applicant to meet with the Dalton Conservation Commission,” he said.

Peter Blair of the Conservation Law Foundation asked whether the amended application would be considered part of the old application or an entirely new application. Trowbridge said that is question for the state Department of Justice to determine.

If it is determined to be a new application, the Dalton Conservation Commission would be able to formally enter the review. The commission missed a deadline to be part of the process when the original application was filed, so has only been able to participate in public comments.

Rep. Edith Tucker asked the panelists if they felt new legislation would help to synchronize their reviews with the federal process under the Army Corps of Engineers, since the feds may want to look closely at the cumulative effects of all three phases of the operation.

Trowbridge said the Army Corps review will incorporate federal wetlands standards under the Clean Water Act. “For this case, triggering the National Environmental Policy Act will broaden the scope of the review,” he said. “To incorporate that into New Hampshire wetlands rules is not appropriate. It’s a separate but close process.”

Finkel has commented in an email, “I just think it’s one thing to claim to “coordinate” by doing the opposite (!), but the idea that a permit to destroy something is a “renewable” decision is just nuts.”

T.P. Caldwell is a writer, editor, photographer, and videographer who formed and serves as project manager of the Liberty Independent Media Project. Contact him at liberty18@me.com.