Arnie Alpert is a retired activist, organizer, and community educator long involved in movements for social and economic justice. Arnie writes an occasional column Active with the Activists for InDepthNH.org.

By ARNIE ALPERT, Active With the Activists

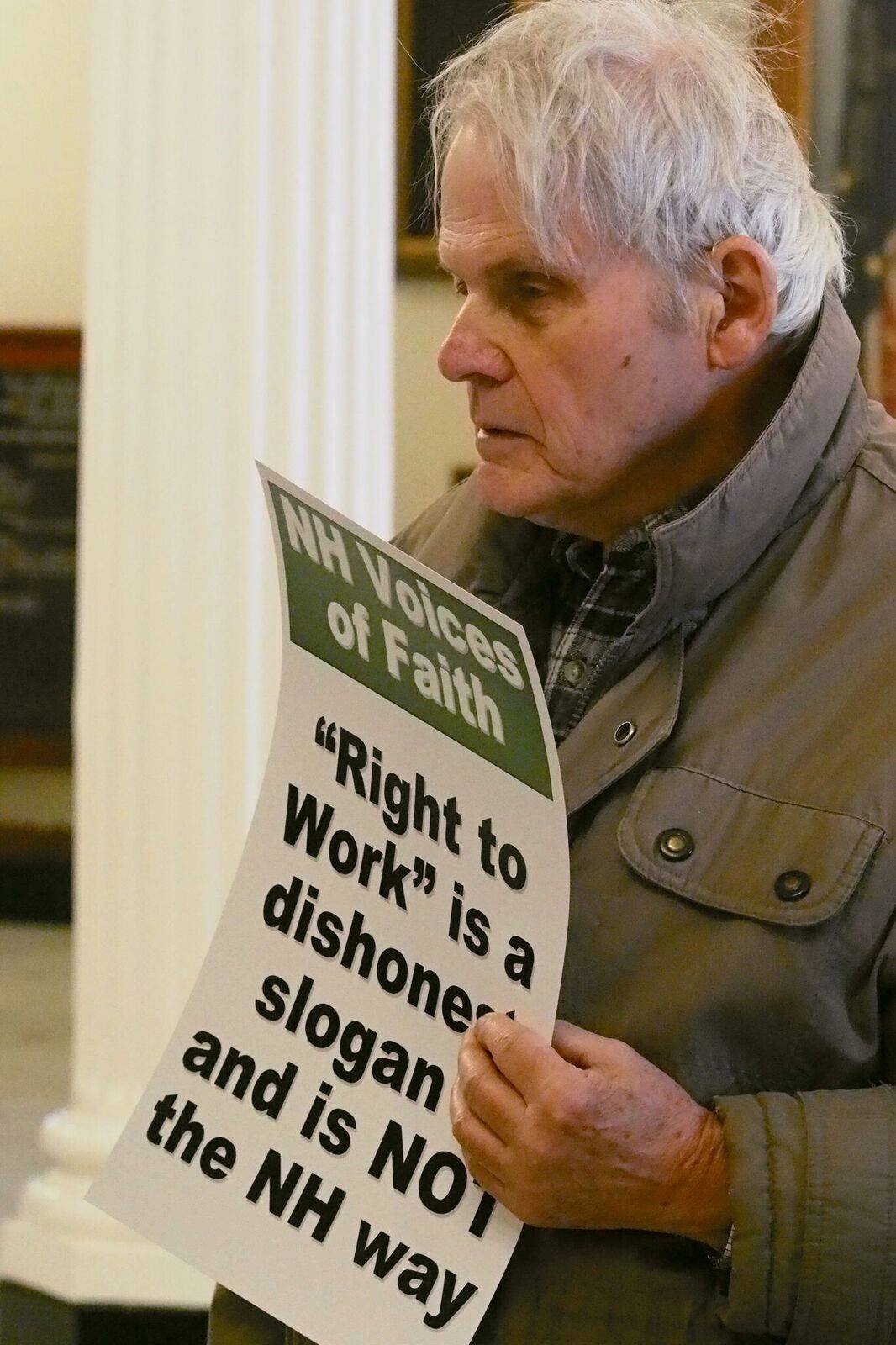

At last week’s six-hour hearing on a bill to weaken the power of organized labor, lessons on theology were mixed in with statements on labor law, economics, and the role of unions.

“Catholic social teaching beginning with Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical, Rerum Novarum, in 1891, called for the protection of the weak and the poor,” explained Ed Foley, a retired sheet metal worker who led the NH Building Construction Trades Council.

Since then, Foley told the House Labor Committee, “there has been over 130 years of unbroken tradition within the Catholic Church supporting the rights of workers to organize unions as essential for economic justice and the dignity of the human person in the workplace.”

The issue at hand is a concept known as “right to work,” a proposal that has come before the legislature virtually every session since the late 1970s. In a narrow sense, “right to work” bars employers and unionized workers from adopting agreements which require employees to join a union or pay a fee in lieu of union dues. But the name is misleading, Foley explained.

“It doesn’t create any new rights for working people. This law seeks to impede worker solidarity and create divisions in the workplace. It sets the economic interests of a single individual against the common good of the group as a whole.”

The idea had its birth in the Jim Crow south in the 1940s, testified the Rev. Dr. Gail Kinney, who chairs the Economic Justice Team of the United Church of Christ’s New Hampshire Conference. Espoused by white supremacists, “right to work” was “all about trying to put a divide between Black workers and white workers,” she said, thereby diminishing the power of organized labor in the workplace and in the wider community.

In that sense, it’s been a smashing success: unionization rates in right-to-work states are about half what they are in free bargaining states. And that’s why the Virginia-based National Right to Work Foundation and its New England chapter come back to the State House year after year, armed with anti-union invective.

“We know all too well that in the states where it has been adopted, this legislation has led to lower wages, fewer benefits for working people such as employer healthcare, more dangerous workplaces, higher infant mortality rates and higher poverty rates,” Foley observed. That explains why the proposal’s opponents generally label it “right to work for less.”

“Rarely have I seen a bill that is so avowedly immoral,” the Rev. John Gregory-Davis of the Meriden Congregational Church told the Labor Committee. “What are we afraid of? Are we afraid that if people have the right to organize for better working conditions, they’ll achieve them? I hope so.”

By giving workers a voice, unions enable all workers to achieve fair treatment on the job, including better wages and working conditions. Viola Katusiime of the Granite State Organizing Project, a Manchester-based coalition of religious congregations and community groups, instructed the legislators in how it works, citing a 2016 report by the Center for Policy and Research.

“Unions help to bridge the racial inequality gap, particularly for Black workers in the unions,” she said. “They receive 16% higher wages than their non-unionized counterparts.”

Likewise, they are more likely to have the benefit of employer-provided health insurance and retirement plans. And by standardizing wages for workers doing similar jobs, unions help bridge the racial wealth gap.

“Much has been said of the heroism of essential workers, but weak labor laws and disregard of employers for workers’ well-being has put a terrible burden on those forced to work for low wages, without adequate protective gear, without paid sick leave, and with no protections for speaking up to demand better treatment,” added Maggie Fogarty of the American Friends Service Committee, an organization which bases its work on the principles of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). “The pandemic makes a compelling case for strengthening – not eroding – the ability of workers to collectively bargain,” she emphasized.

It’s not just union members who stand to benefit but the community as a whole. Bob Dunn, Public Policy Director for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Manchester, said it’s really about “the common good,” a principle expressed in Pope John Paul’s 1981 Encyclical on Human Work. “This reference to the common good should be closely noted,” Dunn said in a written statement opposing the right-to-work” bill, “because the common good is not just a cornerstone principle of Catholic social teaching, but the foundational purpose of our state government as well. To fulfill the principle of the common good, both unions and employers are obligated to work not just to advance their own interests, but to advance economic justice and the well-being of all.”

SB 61, this year’s version of right-to-work,” has already passed the Senate and has been backed by Gov. Chris Sununu. That’s why the fight in the House is especially fierce this year. At last week’s hearing, roughly eight times as many people registered and testified in opposition to the bill as those who supported it.

The Labor Committee plans to consider the bill in executive session on March 30, which means it could get to the House floor in a mammoth three-day session the following week.

The Rev. Jason Wells, Executive Director of the NH Council of Churches, wants legislators to know the council’s nine member denominations say right-to-work” is wrong for New Hampshire. “All of these denominations express Biblical and historic support for labor unions and the right of workers to organize for better conditions,” he wrote in a letter to the Labor Committee. “All of our denominations urge that we support labor unions and collective bargaining and to strengthen (not weaken) them when we are able.”

For Rev. Wells, the timing of the debate, coinciding with the observances of Passover, Easter, and the anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is significant. The rituals of the season “should remind us that if our hearts be with God, we must also have a heart for our neighbors,” he says. “And if our heart be with our neighbors, that must include our working neighbors who are counting on us to once again stand with them and oppose SB 61.”

InDepthNH.org takes no position on political issues but welcomes divere ideas. email nancywestnews@gmail.com