By NANCY WEST, InDepthNH,org

CONCORD – The New Hampshire Union Leader argued Wednesday in Merrimack Superior Court that certification hearings before the Police Standards and Training Council should be open to the public. The council countered saying they should be closed unless the police officer specifically requests an open hearing.

Represented by attorney Gregory Sullivan, the state’s largest newspaper argued that nurses, doctors, lawyers, judges and others all hold public disciplinary hearings. Sullivan had also sought information about council hearings on Manchester Police Officer Aaron Brown and Ossipee’s Justin Swift.

“…(P)olice officers with the powers of arrest and the power of deadly force – that the public has the most obvious interest in knowing whether or not they are qualified and not something that should be done in secret,” Sullivan said.

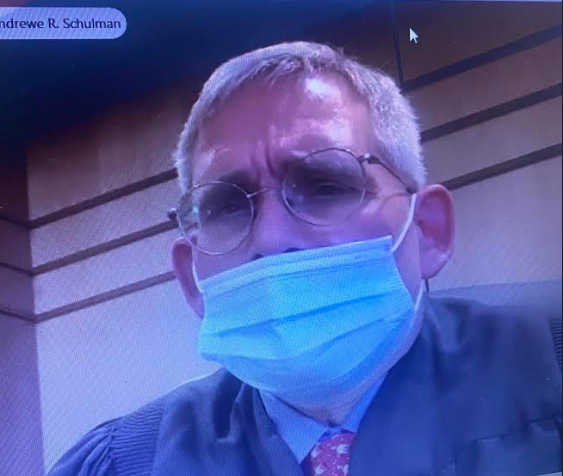

Assistant Attorney General Jennifer Ramsey told Judge Andrew Schulman that the Police Standards and Training Council has been exempt from open hearings because there is nothing specifically in the law requiring it to have open hearings.

Council hearings have been closed for as long as anyone can remember, Ramsey said, also citing exemptions in RSA 91a, the state’s right-to-know law, to back up the council’s position.

Ramsey said the state Supreme Court makes rules for hearings relative to judges and lawyers, and lawmakers have decided which state agencies are required to have open disciplinary hearings. As a matter of public policy, the legislature has said some hearings need to be public such as those for doctors and nurses.

There is no such requirement in the law for the Police Standards and Training Council, Ramsey said.

“The legislature is the right place to make that policy decision,” Ramsey said.

Schulman asked Ramsey: “Can you think of any regulatory board that doesn’t have public hearings?”

He recalled starting out as a lawyer in 1985 when disciplinary proceedings for lawyers were by and large confidential. “It wasn’t a good rule,” Schulman said, adding he was glad that today attorney and judge discipline is more transparent.

“Is there anybody left?” Schulman asked.

Ramsey said she didn’t know but of the other state boards regulating many professions in New Hampshire, the ones she examined all had statutory language requiring open discipline hearings.

“Those statutes provided for public adjudicatory hearings where the legislature had stepped in and said as matter of public policy these are important issues the public has right to know about,” Ramsey said.

Schulman said he understood the legislature had statutory requirements for doctors and others.

“On the other hand, it would be a weird day if all the other professions had open hearings except for police officers. That would be weird…,” Schulman said.

Schulman said with police officers there is a high public interest, a great public trust and yet wrongdoing by barbers and nail stylists would be heard in public.

Last October, Union Leader reporter Mark Hayward reported that 54 state licensing boards oversee professions ranging from nursing to home inspections and they all have public disciplinary hearings.

Ramsey said Attorney General Gordon MacDonald has said he would support a legislative change to make the Police Standards and Training Council’s hearings public.

Ramsey also outlined why the documents requested by the Union Leader were redacted, including honoring redactions that had been made in the case of Manchester Police Officer Aaron Brown by the Manchester Police Department.

Ramsey said she didn’t see the need for Schulman to do an in camera review, but would provide the unredacted documents if the court deemed it necessary.

Attorney Sullivan asked for the in-camera review because some of the documents he received were totally redacted.

“I’ve got all these black pages,” Sullivan said. “I can’t argue that this document should be released because I don’t have the vaguest notion what’s on it,” Sullivan said.

Sullivan moved on to argue why the hearings should be open.

“There’s no statute that says courtrooms shall be open to the public,” Sullivan said. They are open because of the Constitution and case law, he said.

“When we talk about the officer whose hearing is being held having the right to say yay or nay on the public knowing what’s going on, I would analogize that to all the criminal defendants in your courtroom from now on, following the government’s reasoning, would be able to say, ‘no I don’t want this in public, my grandparents might see it.’

“It doesn’t work that way. We have an open and accessible government as a result of our Constitution and our right-to- know law,” Sullivan said.

Schulman asked about the difference between having an adverse effect on someone’s reputation and invasion of privacy.

“I don’t think it matters because I don’t think a police officer has a recognizable privacy right with respect to the performance of his or her public duties,” Sullivan said.

Schulman took the public records case under advisement.