Active With The Activists

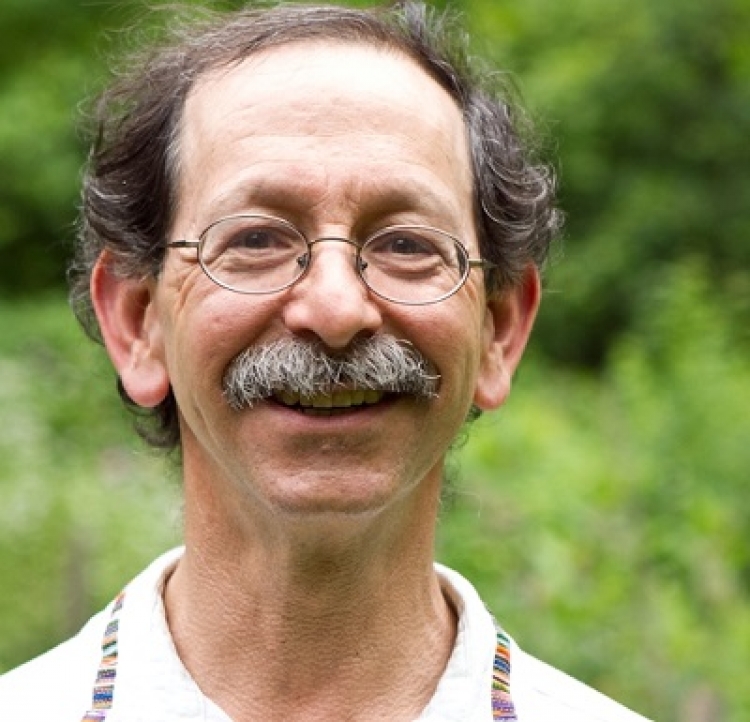

By ARNIE ALPERT for InDepthNH.org

Alex Balcum “would count your buttons and proceed to push all of them,” recalls a homeless outreach worker, but he was “also one of the kindest souls we had the pleasure of working with.”

He died in July in Rochester, one of 59 people whose lives were remembered Monday evening in Concord at the annual Homeless Persons Memorial Day vigil.

They were mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, and at least one grandfather. They were veterans of the armed forces, musicians, and church goers. One of them has been president of the NH Gyrocopter Club. Some were well known, especially to staff and volunteers at the state’s emergency shelters and soup kitchens.

Some were remembered only with a first name. Their deaths in the past year were caused, at least in part, by their experience of homelessness, an all too common condition in New Hampshire and throughout the United States.

One by one, their names were read out as the sky over Concord grew dark on the longest night of the year, the winter solstice. With each name, a volunteer stepped forward and placed an electric candle on a table visible to the 75 or so participants who stood by silently, perhaps reflecting on the lives of each individual.

This year’s vigil was led by the Rev. Michael Leuchtenberger, pastor of the local Unitarian Universalist Church and a board member of the Concord Coalition to End Homelessness, which was one of two dozen sponsoring groups. Prior to the reading of names, the Rev. Kate Atkinson of St. Paul’s Church read a poem, Susan Brewer of the local Baha’i Faith offered a commentary, and Ellen Groh of the Concord Coalition read Governor Chris Sununu’s annual Homeless Memorial Day proclamation.

As an annual ritual, observed in Concord for the past two decades, the event is an act of public witness to the human toll of homelessness. While individual deaths may be attributed in part to addiction or mental illness, complicated by a global pandemic, no one doubts that the primary problem is the state’s chronic shortage of housing affordable to people with low incomes.

The Governor’s Council on Housing Stability says the 2020 median rent for a two-bedroom unit in NH is $1,413 per month, up 5 percent from the previous year. With prices that high, the number of people who face “housing instability” is much larger than the number who are actually homeless, they said in a report issued a week ago. Citing figures from the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the NH Coalition to End Homelessness says high rental costs mean an individual earning the minimum wage would have to work 129 hours a week, 52 weeks a year, to afford a typical 2-bedroom apartment. Even at $15 an hour, 65 hours of labor would be needed. For too many people, the math wasn’t working even before the pandemic.

According to the NH Coalition’s annual report, released on Dec. 17, the state’s homelessness crisis was already worse than the prior year when the coronavirus hit and spread. With the pandemic, rising unemployment, especially in low-wage sectors like retail and food service where workers were already housing insecure, placed even more people at risk.

“Without additional rental assistance, those who are precariously housed and who are unable to find immediate employment face the threat of eviction and homelessness, placing even greater stress on the homeless service system in New Hampshire,” the coalition says.

The coalition says the crisis is urban and rural, felt in every part of the state. They also report that African Americans and Hispanics are disproportionately at higher risk of becoming homeless.

When the pandemic hit, members of the homeless community were apparently more tuned in than some of our legislators. Aware of the hazards posed in densely populated shelters, more people who were homeless apparently decided to try to live outdoors. And while living in a tent might have enabled safer social distancing, it also distanced people from plumbing, heating, communication links, and social supports promoted by the state’s network of emergency shelters. It wasn’t a solution.

Monday’s vigil in Concord was one of nine held statewide, all timed to coincide with the year’s longest night and the official beginning of winter. Like the public encampment outside the Superior Courthouse in downtown Manchester earlier this year, the vigils bring visibility to a problem that those of us who are comfortably housed might otherwise choose to ignore.

The report of the Governor’s Council of Housing Instability, like reports that preceded it, lists concrete steps to take, with an emphasis on data analysis and planning and an eminently practical suggestion that vacant commercial space be converted to housing. Some measures should be obvious; in addition to more studies and better coordination between agencies, we need more investment in affordable housing, more services for the chronically homeless, and more attention to the educational and psychological needs of children who lack a stable place to live. As the NH Coalition proposes, “all housing and homeless policy recommendations and program initiatives need to be assessed and developed through a racial equity lens.” And while the governor might not want to hear it, the people who suffer housing insecurity would benefit from a higher minimum wage. We’re not lacking in solutions; we’re lacking in political will.

With the State House lit up in the background, the Rev. Jason Wells of the NH Council of Churches and the NH Poor People’s Campaign finished the program by rallying support for an extended moratorium on evictions in the COVID-19 relief bill that was lurching toward final approval. That would be a good step. When Homeless Persons Memorial Day comes around 12 months from now, we can look back at whether any appreciable progress was made while we read another list of people whose deaths were caused, in part, by our lack of political will.

The opinions expressed belong to the writer. InDepthNH.org welcomes diverse opinions at nancywestnews@gmail.com