Health experts today acknowledge the health and welfare of New Hampshire children and adults is influenced by climate change.

“The impacts of a changing climate include direct and indirect effects on public health, and New Hampshire needs to be better prepared,” said Joan H. Ascheim, New Hampshire Public Health Association’s Executive Director. “More education is essential and strong policies to forestall the effects of climate change are critical and time sensitive.”

We’ve made some progress since 2010 when a small number of professionals in New Hampshire began to study local connections and increase awareness among peers and the public. Back then I served on the Climate Change and Health Improvement Planning Committee convened by the Division of Public Health Services and Department of Environmental Services to begin to bring climate into focus within the state.

Committee members envisioned that “New Hampshire and its local communities have in place organized, coordinated and effective systems to identify, prevent, prepare for, and respond to health hazards associated with our changing climate.”

In 2014 the University of New Hampshire issued an assessment of climate change and public health. Armed with this report and money and guidance from the Centers for Disease Control, DPHS offered small grants to our Regional Public Health Networks to investigate potential climate impacts and associated health burdens within their service areas.

Resulting climate and health adaptation plans from the Monadnock region focused on extreme weather, the Upper Valley on heat stress, and the Lakes and Seacoast Networks on Lyme disease.

Underfunded and capacities stretched, these local networks nevertheless work to coordinate and deliver public health services in their communities, including helping communities prepare for a variety of increased health burdens influenced by a changing climate.

“We build local relationships and are great avenues to increase awareness about the connections between public health and climate change,” said Mary Cook, Public Health Emergency Preparedness Manager for the Seacoast and plan leader.

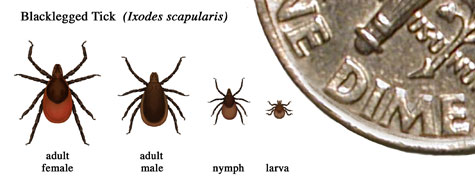

Lyme disease is a serious problem in the state. New Hampshire ranks fifth nationally for confirmed cases of Lyme disease, and warmer winters contribute to the increased survival of ticks that transmit the disease. Interventions developed in the Seacoast plan made a difference, according to Camp Lincoln director Reid Van Kaulen, who understands tick borne disease is an issue people should be aware of and deal with proactively.

“Training helped. It was important that camp staff learned the potential harm of ticks, how to identify them, and prevention techniques,” Van Kaulen said.

Heat stress incidents are also projected to increase. The years between 1998 and 2009 averaged 125 heat-related hospital visits in New Hampshire. A 2019 study by the Union of Concerned Scientists called “Killer Heat” found that while New Hampshire has only experienced three days per year on average with a “feels like” temperature that exceeds 90 degrees Fahrenheit, that number will increase to 23 days per year on average by midcentury and 49 by the century’s end.

Warmer temperatures create more ozone; future increases in summertime ozone days and a longer summer ozone season will result in more pollution-related cardiorespiratory illnesses, including asthma. In 2015, there were 18,000 New Hampshire children living with asthma, and ozone can affect their ability to breathe. Our health system needs to be prepared for higher future average temperatures.

Higher temperatures are tied to greenhouse gas emissions. At the present rate of emissions, the annual costs of climate-driven, premature ozone-related deaths nationwide are estimated to be $9.8 billion in 2050 and $26 billion by 2090.

Science tells us that by reducing emissions we can expect to reduce the annual costs of premature deaths by 30 percent.

The New Hampshire Public Health Association is aware of the connection between emissions and human health. In 2016 NHPHA revised its climate change policy statement to include greenhouse gas emissions: “...current policy tools do not adequately address the root causes through vigorous efforts to reduce greenhouse gases. … We must find additional ways to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels…”

Addressing the root causes of air pollution contributing to respiratory disease means taking the emissions reductions fight to federal and state elected officials. Our federal lawmakers are well positioned to support a national renewable energy standard.

Senator Tom Udall introduced Senate Bill 1974, the Renewable Energy Standard Act, to create a national standard for renewable electricity generation by utilities in each state. Absent a national standard New Hampshire remains the nation’s tailpipe and victim of air pollution from upwind states like Ohio.

At the state level New Hampshire must clean up its transportation sector, responsible for ground-level ozone and 42 percent of New Hampshire’s greenhouse gas emissions. Transportation solutions are not adequately addressed in the state’s 2018 strategic energy plan.

Officials are watching a 12-state effort to incentivize low-carbon transportation solutions called the Transportation and Climate Initiative. State lawmakers will soon debate bills on road usage fees applied to low emissions vehicles.

Another bill will consider adopting clean car standards similar to those applied successfully in surrounding states. Legislators may also debate establishing a commission to identify a statewide emissions reduction goal – and the pathways to meet it.

There is much work to be done on all fronts. Follow Clean Energy NH as the go-to resource to monitor Concord happenings. And consider registering for a climate and health webinar organized by the Antioch NE Center for Climate Preparedness and Community Resilience.

Today, circumstances demand that we strive to rapidly reduce heat-trapping emissions, the root cause of climate change, and alleviate climate related health burdens – and do so simultaneously.

Roger W. Stephenson has been involved in the communication of climate change science and solutions since 1991. He is the Northeast advocacy director for the Union of Concerned Scientists and lives in Stratham, N.H. He has a B.S. in zoology and a graduate degree in wildlife biology from the University of New Hampshire. He writes Field of View: Climate Change Through a New Hampshire Lens as a public service and InDepthNH.org distributes it to all news outlets in New Hampshire. This column is based on science performed by researchers at leading institutions and on the National Climate Assessment, a congressionally mandated report developed by thirteen federal agencies to help the nation “understand, assess, predict and respond to” climate change. The opinions expressed belong to the writer and do not reflect the publication’s views.